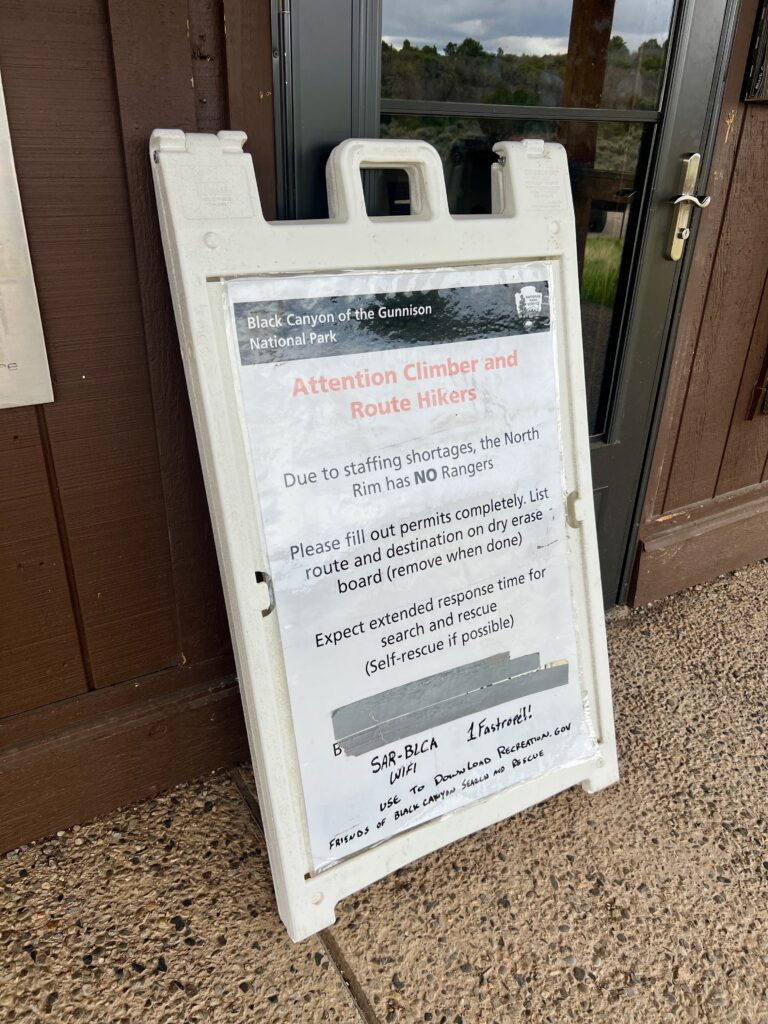

Ranger staffing shortages. Resignations at key park leadership roles. And at Colorado’s iconic Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, a sign on May 29 asking visitors to “self-rescue” in case of emergency, because no ranger staff were available at the canyon’s north rim.

The country’s national parks have faced staffing woes and maintenance backlogs for years. But advocates say those issues have been exacerbated by firings and buyout offers from the Trump administration.

Around 2,500 people—nearly 13% of the National Park Service’s workforce—have been laid off, taken early retirement or accepted buyouts since January, according to data from the National Parks Conservation Association (NPCA), a nonpartisan advocacy group.

“[Staffers] have been forced out. They've been under duress, they've taken early retirement,” said Tracy Coppola, an NPCA program manager.

It’s unclear how many of those staffers are located in Colorado, which is home to four national parks and several other wilderness areas, national monuments and other sites maintained by the service.

In May, the Trump administration released detailed budget blueprints for the next fiscal year, which begins on Oct. 1. If enacted, the proposal would slash the park service’s budget by over $1 billion, including $900 million used to operate parks, according to an analysis by NCPA.

“This presidential budget would gut the national park system,” Coppola said. “It would be the largest cut in National Park Service history, and the history goes back over 109 years.”

The National Park Service did not respond to questions about how the proposed cuts would affect park operations or how staffing cuts have affected Colorado parks like Black Canyon of the Gunnison.

On May 22, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a budget bill that would strip the service of over $250 million in funding provided by the Inflation Reduction Act, a Biden-era climate law, for staffing and climate-related projects.

The presidential budget is not final — it’s essentially a wishlist of proposed cuts. The U.S. Senate is now debating the budget bill, and has the power to restore or make deeper cuts to the park service. Some senators have expressed concern.

“No matter which way you cut it, these reckless cuts hurt Coloradans,” Senator John Hickenlooper (D-CO) said in a statement. “They’ll open our backdoor to wildfires and run our national parks and forests into disrepair … We’re fighting their senseless attacks with everything we’ve got.”

Cuts could have a huge impact in Colorado

While lawmakers wrangle over the budget, the service is also enjoying a banner year. Visitorship across all parks reached a record high in 2024, and over 7 million people visited Colorado park sites last year.

In April, Interior Secretary Doug Burgum issued an order to keep the lights on at national parks and review staffing levels. Coppola of NPCA said the order creates a potemkin village of sorts, where parks remain open despite shoestring staff.

“To keep these parks open and have this image of a visitor experience that is untouched by all this evisceration, it’s a mirage,” she said.

Colorado is also home to several vital NPS research and planning centers for the entire parks network. The Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Directorate, in Fort Collins, helps manage water, wildlife and other biological resources for the entire park network. The Denver Service Center manages planning and construction for the entire service, while the Intermountain regional office in Lakewood oversees 87 park sites across 8 states, including Colorado.

Coppola said that the scientific staff at the Fort Collins office has been cut, impacting the ability of the service to conduct things like air quality monitoring or dark sky certification at parks.

“A lot of those staff have left—they’ve been forced out, they’ve been really put through hell,” Coppola said.

“The long-term protection of parks can only succeed with that broader workforce of planners, scientists, support personnel, and that is being lost.”

The Park Service did not respond to a request for comment about staffing levels at the Fort Collins directorate office. CPR News could not immediately confirm staffing levels.

The lease for the directorate building was also briefly listed for termination on a Department of Government Efficiency website, but that list was later taken down. Coppola said the lease in Fort Collins is still in effect.

To achieve the proposed cuts while keeping major parks open, NCPA estimates that the federal government would have to offload nearly 350 smaller park service sites to states, or close them outright.

That could include the Amache National Historic Site in southeast Colorado, which was formally established just last year. It commemorates the government’s internment of thousands of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

It is likely to see far fewer visitors than an established park like Rocky Mountain, and bring in less revenue as a result. But Coppola said that misses the point.

“Parks provide that added benefit of economic growth for our state, but that’s not why they were created,” Coppola said. “They’re created to tell the story of our country.”