This story was produced as part of the Colorado Capitol News Alliance. It first appeared at coloradosun.com.

All Walsenburg Interim City Administrator John Galusha knows about the plans for the long-closed private prison in the city he oversees is what he’s read in the news: Immigration and Customs Enforcement is considering reopening it to detain immigrants.

And he’s not alone.

Huerfano County Administrator Carl Young doesn’t know if the prison will reopen. And Colorado Springs Mayor Yemi Mobolade and Hudson Town Manager Bryce Lange are similarly in the dark about proposed plans to reopen detention facilities in their communities.

Most local government leaders reached for this story said the private prison companies that own the facilities wouldn’t need local government approval to reopen them as-is. But they would need local resources, like water and wastewater handling, to operate, making a heads-up helpful.

“It would be nice to have some advance warning,” said Galusha, who started in his current role just a few days ago after serving about two decades in county government. “A week or two, so we could order supplies,” like wastewater treatment chemicals.

The officials expressed optimism and skepticism about the prospect of private prison companies reopening facilities in their communities to detain immigrants. For some, it could be an economic boost, they said. For others, not so much.

In other states, though, communities are fighting back against immigrant detention plans. The city of Leavenworth, Kansas, filed a lawsuit to block private prison company CoreCivic from reopening the prison there as an immigrant detention center. Union County, New Jersey’s manager said last week the largely shuttered county jail can’t be used for immigrant detention after protests.

ICE spokesperson Steve Kotecki declined to comment on the record about the agency’s plans to expand immigrant detention in Colorado. The agency already detains immigrants at a facility in Aurora that is owned and operated by the private prison company Geo Group.

But in records obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union, private prison company proposals in response to a request for information from ICE in February show interest in reopening shuttered facilities in Walsenburg, Colorado Springs, Hudson and La Junta to detain immigrants.

Republicans in Congress voted earlier this month to increase ICE’s annual budget to about $28 billion from $8 billion, making it the highest funded law enforcement agency in the country. The extra cash increases detention capacity from the currently funded level of a daily average of about 57,000 people to at least 100,000. ICE detains most immigrants in facilities run by for-profit companies, which have a history of mistreating people.

What that means for Colorado remains unclear. Local leaders are left with only clues.

A representative of CoreCivic, the company that owns the Huerfano County Correctional Center in Walsenburg, emailed Young, the county administrator, March 31 to say that the company had toured the facility with ICE, according to an email obtain by The Sun.

“At this time, we have not finalized a contract and we are waiting for (Department of Homeland Security) to determine their need in the Colorado area,” the representative said.

Jobs have been posted for work in Walsenburg

Earlier this month, CoreCivic posted a job listing for detention officers at the Walsenburg facility, offering $31.50 an hour, or about $65,000 for a full-time position, “contingent on contract award.”

That’s far more than the Tennessee-based company is offering for officers at the other two prisons it owns in Colorado in Las Animas and Olney Springs. The company is also hiring for officers at its shuttered Kit Carson Correctional Center in Burlington “contingent on contract award.” Kit Carson County Commissioner Stan Hitchcock said he has not heard from CoreCivic about reopening the prison.

Galusha said he’d welcome the prison jobs in Walsenburg. The city of about 4,600 people has an employment rate of 37% and a median household income of about $50,000, far below Colorado’s $93,000, according to the most recent census figures.

CoreCivic spokesperson Ryan Gustin referred questions about the company’s contracts with ICE to the federal agency.

Huerfano County residents have shown up at recent government meetings to voice their opposition to ICE reopening the Walsenburg facility, The World Journal reported. Galusha said protests are misguided because the city’s hands are tied.

“The reality is that the city does not have control over the situation,” he said.

Another proposal in response to ICE’s request came from Apex Site Services, a Texas-based company that builds temporary structures for the military and in response to disasters. Apex said the company found a property in Walsenburg along Colorado 69 where it could “construct and staff a soft-sided facility.”

Young, the Huerfano County administrator, and Galusha said they doubted such a facility would be feasible in Walsenburg.

“Huerfano County has strong winds,” Young said.

Just north of Denver, in Hudson, real estate company Highlands REIT in February submitted to ICE a proposal to reopen the shuttered Hudson Correctional Facility it owns. In March, CEO for the Chicago-based firm Robert Lange emailed Bryce Lange, the town manager, asking about what permits would be needed to reopen. Though they have the same last name, the two are not related.

“If we are able to secure a contract for a population things could move very quickly,” Highlands REIT’s Lange said in emails obtained by The Sun through an open records request.

Bryce Lange said he initially thought the company would need permits to reopen, but Hudson’s legal team later found that the company could reopen without town approval.

“The town doesn’t have land use authority like it would over a private development,” said Lange, the Hudson town manager. “The federal government is more or less exempt from those more routine processes.”

If the Hudson Correctional Facility reopens, Lange said it won’t make much of a difference to the town of just 1,600 people in Weld County. There, the employment rate and median household income are higher, 60% and about $70,000, respectively.

“We have a lot of great stuff going on,” he said, citing new truck stop amenity stations opening. “I don’t know that we’re looking for a Hail Mary with the prison reopening.”

Highlands REIT could not be reached for comment for this story.

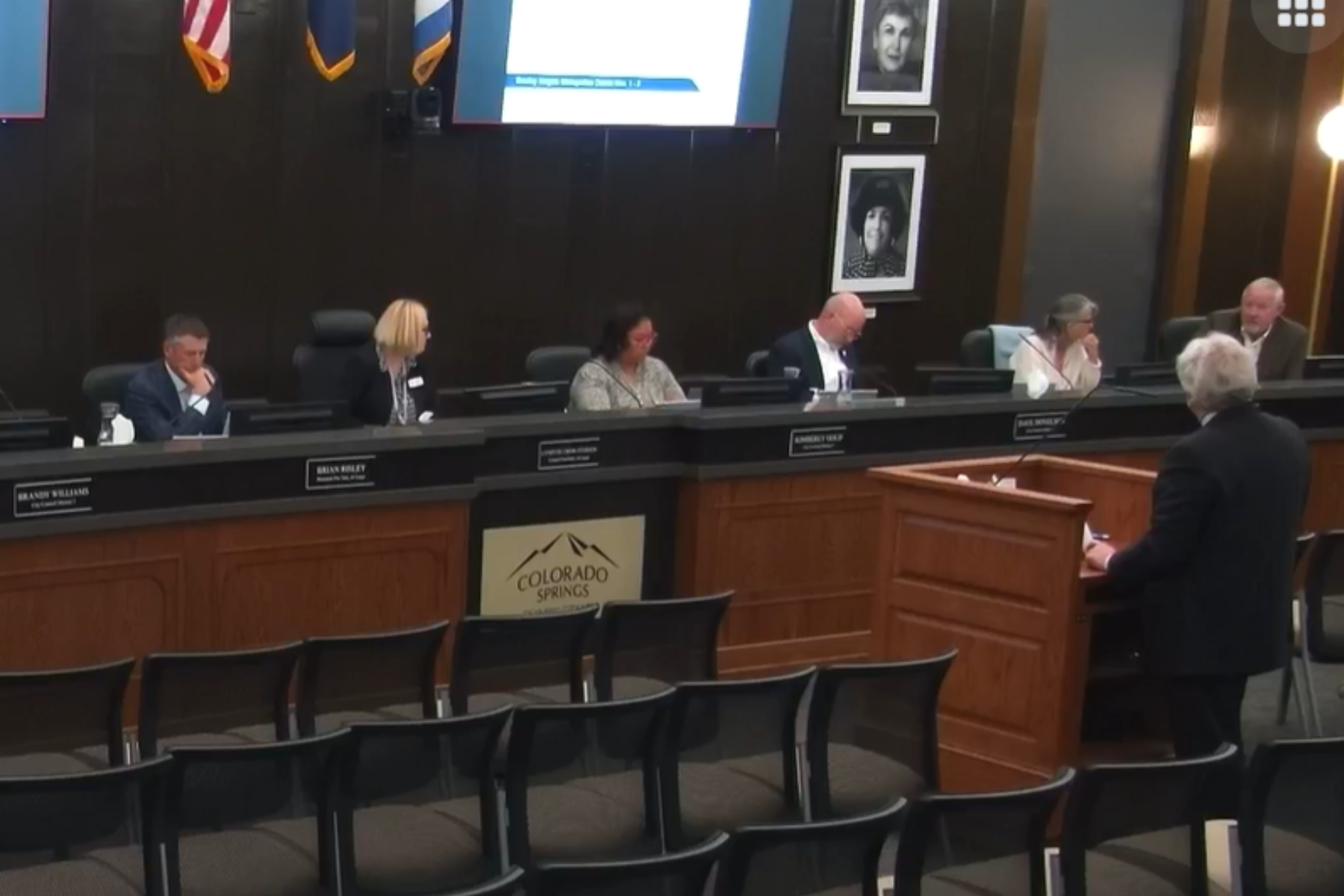

Joe Hollmann, spokesperson for Colorado Springs Mayor Yemi Mobolade, said the mayor hasn’t heard from ICE or the private prison companies interested in reopening facilities within 10 miles of downtown: Florida-based Geo Group’s Cheyenne Mountain Center and Georgia-based The Baptiste Group’s Parkmoor Village Health and Rehabilitation facility. It’s unclear what city approvals the companies would need to reopen.

Pikes Peak Regional Building Department spokesperson Greg Dingrando said the department has not received any new plans or permit requests for the facilities. Natalie Sosa, a spokesperson for El Paso County, said the county has no specific knowledge of plans related to the facilities.

Christopher Ferreira, spokesperson for Geo Group, referred questions about the company’s plans to ICE.

The Baptiste Group, which also submitted a proposal to reopen its former private school, Colorado Boys Ranch, in La Junta, to detain immigrants, could not be reached for comment for this story.

La Junta City Manager Michael Hart did not respond to requests for comment and a receptionist at the Otero County Commissioners office said the county administrator had not heard from The Baptiste Group or from ICE about their plans.

The murkiness about ICE’s plans comes as immigration arrests quadrupled in Colorado between Jan. 20 and June 26 compared with the same time period last year, according to a Colorado Sun review of ICE data.

But, the Aurora detention facility appears to have many empty beds. As of June 23, ICE was holding an average of 1,159 people each day at the Aurora facility, according to ICE data published by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a research group at Syracuse University, far below its capacity of 1,532 people.

Colorado Capitol Alliance

This story was produced by the Capitol News Alliance, a collaboration between KUNC News, Colorado Public Radio, Rocky Mountain PBS, and The Colorado Sun, and shared with Rocky Mountain Community Radio and other news organizations across the state. Funding for the Alliance is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.