Most of the Intermountain West is in a drought, with nearly 20 percent of the region stuck in the most severe, driest conditions, according to a Tuesday presentation from Colorado state climatologist Russ Schumacher and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The five state region includes Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Wyoming.

August usually stems the tide during drought years — it’s typically the region’s wettest month due to monsoon rains. But this year has proven much drier and hotter than normal, further deepening the drought.

“There’s not a lot of positive signs in terms of the drought situation improving,” Schumacher said. “It will likely get worse, at least over the next few weeks, through the rest of August.”

The worsening outlook comes amid uncertainty over federal funding for drought relief, which Colorado lawmakers are urging President Trump to support.

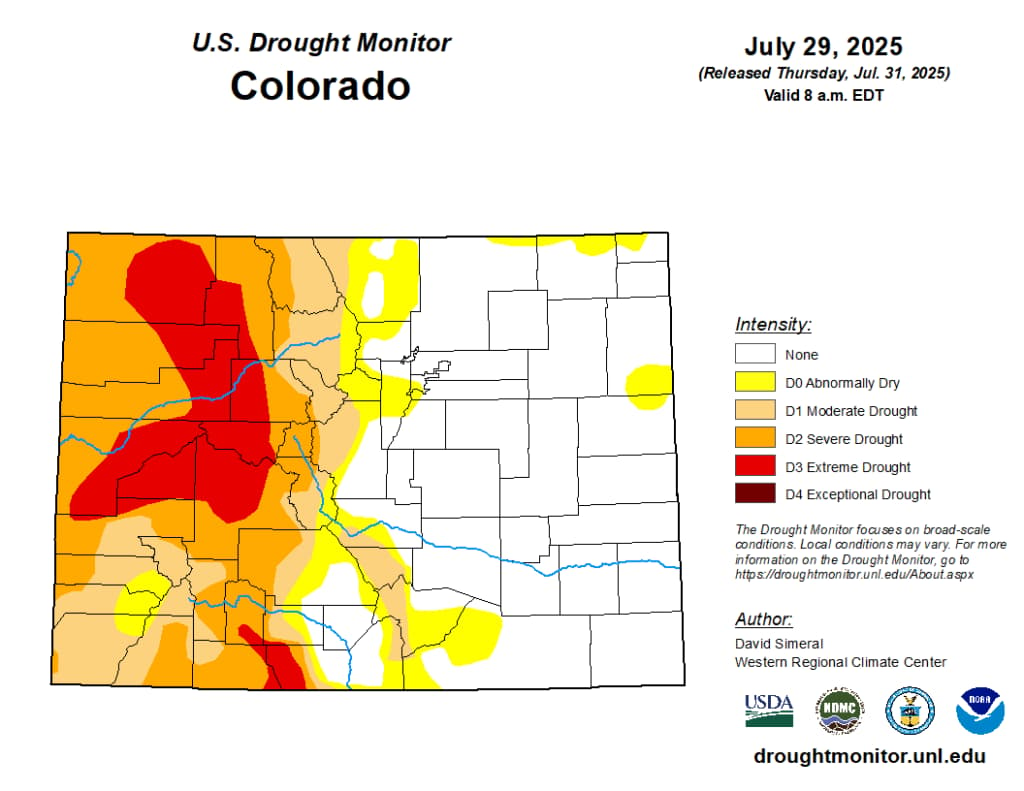

The most drought-stricken areas are west of the continental divide – a scraggly arc of mountain ranges where precipitation eventually drains westward, towards the Pacific Ocean.

The driest conditions in Colorado are largely concentrated on the Western Slope, while much of the Eastern Plains faces little to no drought, and has seen average or above-average precipitation levels since October.

Most of Colorado’s precipitation usually falls east of the Continental Divide, but the Western Slope typically gets much more snowfall, which eventually feeds into streams and rivers that course through the state.

The drought indicators are a far cry from last October, when only 36 percent of the region faced drought conditions, a trend that continued as winter dumped snow in the mountains.

But in April, abnormally hot and dry conditions rapidly melted snowpack and began dumping less precipitation than average across the West. Southern Arizona is even seeing some of its driest conditions over the last 130 years, according to data prepared by the Colorado Climate Center.

Climate change is also accelerating extreme heat conditions for the region, which could prolong future droughts. Denver, for instance, is projected to experience 32 days of extreme heat by 2050, compared to just four days on average between 1976-2005, according to NOAA data.

Wildfires and shrinking streamflows

While drought parches the West, it’s also creating tinderbox conditions for wildfires and shrinking streamflows.

The largest wildfire in the country is currently scorching an area nearly nine times the size of Manhattan near the Grand Canyon, while several fires in Colorado have prompted emergency declarations and evacuations.

There have been nearly double the number of wildfires across the country this year compared to the same period last year, according to data from the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC).

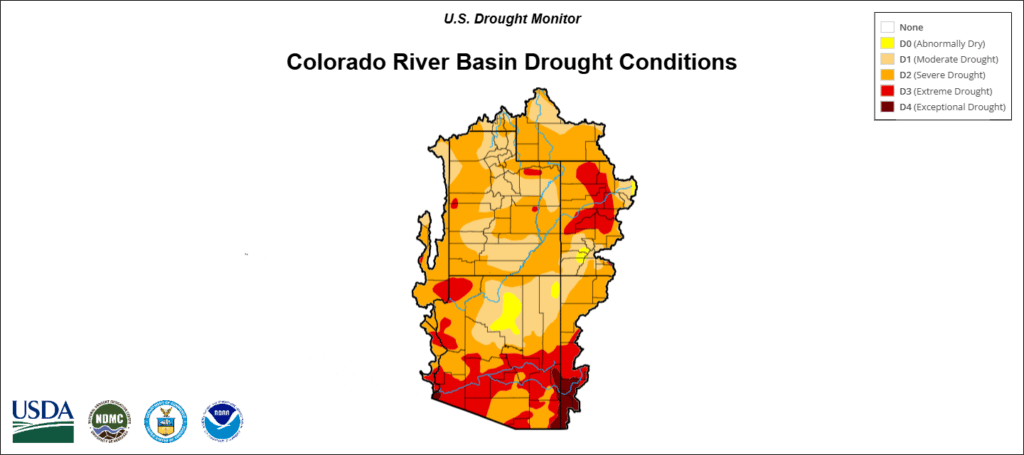

Streamflows in the Colorado River Basin are below average in most areas, according to Schumacher, while water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the largest reservoirs on the Colorado River, are extremely low.

Both those reservoirs are critical sources of drinking water for millions of people, and their storage capacity is fed by precipitation and snowmelt from upstream states like Colorado. Further declines in their water levels could trigger water restrictions.

“Both [reservoirs] are not as low as they were a couple years ago, but again, creeping down towards the all-time record lows in terms of storage,” Schumacher said.

On the White River, near Meeker, Colorado, a stream gauge maintained by the federal government also clocked near record low levels. The area around Meeker is also facing two major wildfires that are incinerating dry, desecrated terrain.