Thousands of students are piling out of “filled-to-the-gills” cars at the University of Colorado Boulder campus this week for the annual move-in day tradition.

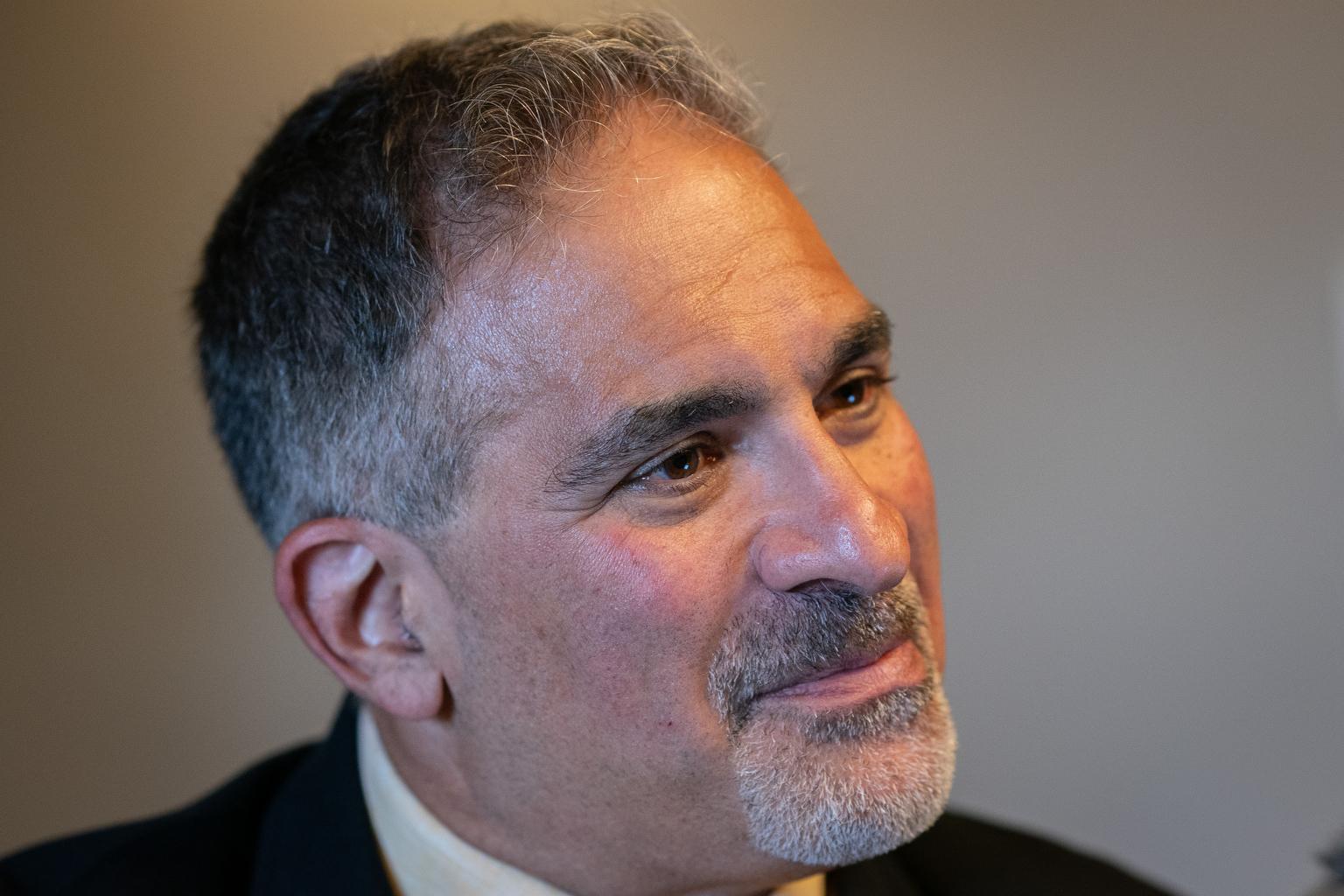

Chancellor Justin Schwartz welcomes a first-year class that comes from all 50 states and 47 countries. Schwartz has been on the job a little over a year.

CPR education reporter Jenny Brundin spoke with him about affording tuition, housing and food at college, federal cuts, DEI and the value of a degree.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Jenny Brundin: You've had a little over a year to get to know the campus, the community, and the state. What has been the biggest surprise or most significant takeaway for you during this time?

Chancellor Justin Schwartz: So many people across Colorado, whether they're engaged with us or not, really care about each other, about the state, that our mission really still resonates strongly. No one comes to me and says, "Why are you wasting your time with quantum?" And, you know, the vast numbers of people that come to the Shakespeare Festival and the enthusiasm for the revival in college football. And just across the board, people are excited about what we can do to make their lives better.

Brundin: You've spent quite a bit of time at the outset of your tenure being highly visible, listening, asking questions. Were there some things you’ve observed that aren't so positive?

Schwartz: Our six-year graduation rates are right around 74 percent. I'd love to see that be 10 to 15 points higher. The cost of housing for our students is really high. If a student's paying their tuition but can't afford rent, they still have a problem. And the thing that we don't talk as much about is they can pay tuition, they can pay rent ... food here is expensive, too. What we are talking about much, much more now, when we think about fundraising, when we think about student support, is what's the total cost of attendance? I don't want to talk about diversifying our incoming students; I want to talk about graduating our students. Because bringing a student into CU, having them spend a year or two accruing debt, not a degree, is the worst thing we can do.

Brundin: I noticed that you've had really strong retention in the past year or so. What are some specific things that you've done to keep kids on campus?

Schwartz: It’s one of those, "lots of little things" as much as "one big thing." The Buff Undergraduate Success effort was underway before I got here, which looks at student retention and graduation. In the earlier stages, it focused a lot just on the academic piece. But there's so much more to it. Going back to the housing, so if you can't afford to live in Boulder, you live further away, maybe that's good enough for you financially, but now you're not on campus as much, so you're not getting involved in as many outside-the-classroom things that we know drives success for students. So, trying to look at every facet of the student experience holistically is where we're having the conversations. We've had, as you pointed to, a regularly increasing retention rate and graduation rate, and what I've asked them to do is to bend the curve and accelerate our progress in that area.

Our admitted students for this coming fall, over 50 percent, had a 4.0 in high school. So, the academic quality of our incoming students isn't the challenge. There’re so many layers to student success, which is another way of saying there's so many things that can get in their way. Part of our job is to simply remove those barriers, remove those things that can get in their way, so that they have an easier time of focusing on why they're here, which is to learn, to engage, to figure out what they want to do and who they are, so that when they leave here with a degree, they are ready to do what they want to do in life.

Brundin: I want to shift to the national environment. You've been at the helm during a time of enormous unpredictability, namely with a new president, Donald Trump, trying to completely remake education. How has that changed the way you're doing long-term planning?

Schwartz: For the most part, it's not. We have been doing this for almost 150 years. Next year is our 150th anniversary. We know what our mission is. We are going to create knowledge and disseminate it. External factors don't change all those things. That's our mission. And we've been through periods in 150 years where there was huge federal support for everything universities do, and there's been periods when there hasn't been. There's been periods where there's huge state support, periods where there haven't been, but we just keep doing that mission because that's what we're here for.

Now, does that mean we're just completely blind to what's happening in the world? Of course not, but we're also not going to succumb to the anxiety game. Right now, so many of the potential changes are just that, they're potential changes. And we have an incredibly strong government relations team at the CU system who are engaging through the processes with our congressional delegation, with our Senate team, to make it clear what it is we do and why it's important and why just about everything we do really is apolitical. I mean, is graduating students a political question? I hope not. Is doing research related to cancer a political issue? I hope not.

Do I worry about Pell grants? Of course.

Brundin: Those are the federal grants for low-income students …

Schwartz: The graduate Pell grants program was eliminated, which is disappointing because graduate education is important. But I think the real question is going to be, to what extent are Pell grants funded in next year's budget. So, we're certainly keeping an eye on that. But we also have the Colorado Promise, which means that our in-state students from families making under $90,000 aren't going to pay tuition either way. If there's a reduction in Pell grants, we'll have to figure out how to cover those expenses in some other way. We have a robust research enterprise and we're obviously going to lobby hard for the NASA budget and the NIH (National Institutes of Health) budget and the NSF (National Science Foundation) budget and the DOE (Department of Energy) budget along with a couple hundred other universities and entities through our congressional delegations.

Brundin: Federal funding makes up about two-thirds of CU Boulder's research funding, nearly half a billion dollars last year. I believe you've lost about 49 grants so far, I think totaling about $30 million. What kinds of research has stopped?

Schwartz: I think that number has actually gone down … I think I heard the system president say 37 grants today. Some of them have come back. And so yes, the loss of those few million dollars is hard to swallow, and it's particularly hard on those researchers. It's a small percent of our overall research enterprise but we’ll fight for every single one of those because we think every one of them is important.

Brundin: Are you expecting more National Science Foundation or National Institutes of Health funding losses? Those are the ones you're talking about when you're saying you're going to fight for that.

Schwartz: Please don't ask me to predict the future!

Brundin: I don't think anybody is at risk of doing that now!

Schwartz: I think it's been a while since our last grant ‘stop order,’ if I'm not mistaken. That doesn't mean that that phase of the administration's putting their stamp on research has ended, but I think really the bigger focus is on next year's budget — making the case for why it's important to understand weather patterns if you're going to fly a plane, and all the things like that that really directly affect the everyday life of Coloradans and Americans.

Brundin: CU plays a big role in the state's aerospace economy. One example is we're looking at a possible 25 percent cut to NASA that could really affect Colorado's aerospace economy.

Schwartz: That certainly would. We're of course working with our congressional representatives from both parties to make the case for why they should represent Colorado and fight for the NASA budget.

Brundin: There's been a lot of political scrutiny at the national level, challenges to diversity, equity and inclusion. CU has been engaged in a years-long effort to boost enrollment of students of color. How do you do that in this environment? Have you found a way to continue to try to engage that population?

Schwartz: Our focus is trying to better represent all the demographics of Colorado, to be seen and be known across all the schools across the state—Front Range, Western slope, Eastern Plains. For us, when we think about how we have a more diverse and inclusive student population, it also includes first-generation students from across the state. It includes rural farmers and ranchers. So, it's not explicitly, "let's just increase the number of African American students. It's, ‘let's really make sure that we're representing the full demographics of the state,’ because we represent Colorado. Now, we've certainly seen some increases year over year in first-year African American students. Having a football coach as widely known as Deion Sanders may have had an impact on that, too. When we look back at how we've been doing with student recruitment in the past, we're very confident that we have been not using discriminatory practices at any stage. It's simply a question of how do we make our case known to students? How do we get them to come and visit?

Brundin: We've talked a little bit about some of your priorities. I'd like to give you the opportunity to talk about some of the other big priorities you'd like to move on. I know leadership in sustainability is big for you.

Schwartz: Yes. Sustainability is a huge piece of what we're trying to do. We can call it sustainability, we can call it climate resilience. One of the primary questions I got from faculty and staff over and over again was, ‘Why is it we're doing so much work in sustainability and we're not known for it?’ And the primary question I would get from students was, ‘Are there going to be more opportunities and offerings for me to have a career in sustainability, and why aren't you doing more to make campus more sustainable?’ It was just this recurring drumbeat from our entire population.

We've just signed a new contract with Pepsi, eliminating single-use plastics. We just got a naming gift from Ford for our indoor practice field, which is net zero energy, because they want to align their electric vehicle positioning with an institution like us. We're making progress on getting more electric buses. I'd love to be able to retire the old expensive diesel buses that we have, not only because of their environmental impact, but maintaining them is not cheap.

We just got this big gift from an alumnus, a $10 million gift over five years to create the Buckley Center for Sustainability Education. This is to resource our faculty, to bring more sustainability into their curricula, and it's also to give real-time experiential learning opportunities to our students and sustainability. And to be clear, that's not a STEM thing; it's across all of our disciplines. We aim to see how we can be a driving force for Colorado to be the most sustainable state in the country. I try to talk about it in a way that makes it clear this isn't a political move. This is simply, "the state of Colorado needs to have water accessibility across the state." That's a sustainability issue. We'd all, I think, like to see better air quality in Denver year-round. We need to have a strong energy infrastructure, particularly if the demands of quantum and AI are going to drive energy demand up; then we need clean, safe ways to produce more energy.

Brundin: I want to ask you about the whole public perception of higher education. On the one hand, you have University of Colorado, especially CU Boulder, having a huge economic impact. I think from commercialization ventures alone, one report shows an $8 billion impact nationally, $5.2 billion in Colorado from 2018 to 2022. You're bucking the trend in enrollment. You have very high enrollment. But — especially as the price of university has risen — more people have this expectation that, ‘oh, a job should be waiting for them at the end of four years.’ And right now, if you have a four-year degree in biology or in the general arts like political science or history or even now computer science, students are often struggling to find a job. Do you feel your mandate is changing in this current era that may require shifting away from some of these traditional science and arts degrees?

Schwartz: It's a great question. One of the challenges, and this is not a new challenge in today's economy or world, one of the challenges in higher ed is what do our students need long-term and what does our society need them to have long-term? One that's had the most glaring shift is computer science. It wasn't that long ago that universities were struggling to hire enough computer science faculty because the demand was so high for students. Now, part of the world has shifted and the demand for computer science graduates has dropped significantly. But this isn't the first time that the tech industry has gone through feast and famine. It's hard to predict.

Five years from now, will the demand for computer science accelerate again because quantum breakthroughs and AI breakthroughs drive it or not? But the flip side of that is a student who is able to get into and graduate from a computer science program at CU Boulder or other major R1 universities has learned how to think. A college degree isn't just the skill of how to code in computer science. It's the skill of how to think, how to assess, input, analyze, and create. One misnomer is that a student who got a degree in, I'll keep picking on computer science, can only get a computer science job. Historically, that hasn't been the case across the board.

It was a year or two ago, there was data that came out showing 15 years post-graduation, philosophy majors were the top 10 for income. They weren't sitting around writing philosophy books to be in the top 10 for income, but the skills they learned getting a philosophy degree made them extremely attractive and extremely successful in U.S. industry.

We see English majors who go back and get an MBA, or we see English majors who go to law school, or we see English majors get jobs in industry and work their way up the corporate ladder in a variety of different ways. The challenges that our graduates are having now, it's not because they got the wrong degree; it's because we have a challenging economy right now. We need to think not just from that perspective of sort of the immediacy of the economic cycles, but really preparing our citizens to be able to think and to be intellectually nimble and agile in a way that they're going to find different ways to contribute over the course of their careers.

Brundin: It sounds like your philosophy is that indeed philosophy degrees can have value when one looks at things long-term and flexibly. The state of Colorado, as you know, soon will have a special session needing to cut more than $700 million. It's going to be a difficult legislative session next winter. If the financial situation got worse, would you consider cutting low-enrollment programs if there wasn't the money to sustain them — like the way the University of Utah’s university board just ordered cuts?

Schwartz: We have actually a very robust structure of reviewing every program in a five-year cycle. We're way ahead of the higher ed industry in having that built into our processes. Let me take you back 35 years ago: Berlin Wall came down, huge spike in demand for people who had expertise in Eastern European economics. Let me take you back to 9/11. All of a sudden, this country had a massive shortage of Americans who spoke Arabic. We are not in a position economically like Utah is. If there's an upside to the fact that we, being (about) 42nd in the country as a state for student support, means that we are not as dependent on the state money as other places are. Now, we appreciate every dollar we get and we need every dollar we get. But we're not going to draconianly eliminate programs solely because the state budget needs to be addressed. We’ve got a great team working the legislature, so I'm confident that we'll come out of this OK. That is not the type of thing that's going to drive us to just eliminate programs.

Brundin: Chancellor Schwartz, thank you so much for your time today.

Schwartz: Thank you as well. I appreciate the time and the chance to chat.