Students from across Colorado are watching closely to see if Colorado’s state board of education Thursday adopts science standards that clarify the link between burning fossil fuels and rising global temperatures — a link they say is the biggest threat to human existence.

The vote comes after pushback from Republican board members and members of the community who’ve petitioned the board to leave climate change out of science standards. Students say right now there are just two references to climate change in 172 pages of science standards.

Aisha O’Neil, a CU Boulder student and one of the organizers students from sustainability clubs across Colorado called Good Trouble Climate Network, worked with the Colorado Department of Education for more than a year to include more references to climate change and its link to burning fossil fuels.

“The primary reason I support updating our science standards to incorporate more climate education is because I was not the only child to find the climate crisis terrifying,” she testified before the state board of education in the spring.

A survey of 10,000 young people from 10 nations in 2021 found nearly 60 percent said the climate crisis had left them “very worried” or “extremely worried.” A more recent study found that among Colorado youth surveyed, about 85 percent are a little-to-extremely worried about climate change.

She said a lot has changed since the board last adopted academic standards.

“In the last seven years, global temperatures, the number of floods and wildfires, the number of climate-related disasters and youth depression rates have all soared. It’s past time that our state recognizes the power of an education, a full and comprehensive education, that allows our youth to advocate with hope instead of fear.”

Lessons in advocacy for Colorado students

Colorado students have played a key role in raising the consciousness of adults — policy makers, board members and others — about the gravity of the unprecedented warming of the Earth’s temperature.

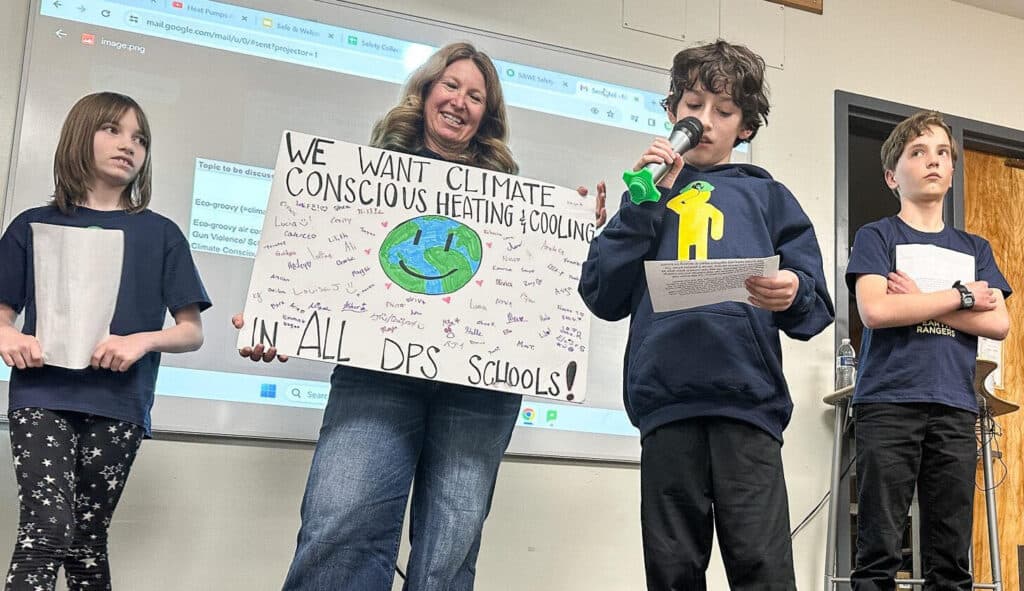

They lobbied in 2024 for a climate seal of literacy endorsement on high school diplomas and other environmentally friendly laws, lobbied for more solutions-based climate education and school district practices, and even Denver middle schoolers lobbied for more efficient heat pumps to heat and cool schools. Students are taking advantage of programs for young people to learn about work experiences to adapt to a changing climate.

In some cases, educators and policymakers have been quick to respond. In other cases, the politicization of climate change in a polarized society and the machinery of bureaucracy has slowed the progress some youth want to see.

Will Colorado add climate change to science standards?

Academic standards guide what students learn in classrooms, from math to music. The state board of education reviews standards in each subject every six years, and science standards are up this year.

For the past year, a group of students has worked with the Colorado Department of Education to propose eight revisions. They recommended more specific information about climate change and its link to burning fossil fuels. Burning fossil fuels changes the climate more than any other human activity.

Brynn Makros, who was a high school senior in Colorado Springs, testified before the board in November.

“Not once was I taught in these three years about climate change,” she said. “Not once. We need to reevaluate our core curriculum now when we still have the chance.”

The department recommended eight revisions based on student feedback and after reviewing academic standards on climate change from other states and a national NOAA climate literacy guide.

But at an April state board of education meeting, four Republican board members pushed back on a proposed revision “to clarify evidence of how burning fossil fuels and other factors release greenhouse gases that cause rising global temperatures.”

They said there are negatives about other forms of energy like wind turbines killing birds. Board member Kristi Burton Brown said that the revision targets just one form of energy and noted that some Colorado students’ parents work in the oil and gas industry.

“Considering our state, considering our districts, to present that to kids as only negative and not touching other forms of energy, I would have a big problem with,” she said in April.

Responses showed a rift in students’ and respondents’ views

The public had a chance to weigh in on the proposed revisions. The department received nearly 1,000 responses, most of them from community members who were neither parents nor school staff. Most respondents didn’t think the proposed revisions improved the science standards. They asked for a more “balanced perspective on fossil fuels and renewable energy.” Some people erroneously referred to climate change as a hoax, while others argued that young people shouldn’t be learning about climate change.

“Students need to learn how to survive in society,” wrote one person. “They do not need to know more about the air or the atmosphere.”

Students largely argued that learning about climate change is critical for their survival. Some wanted the standards to be even more explicit.

One student from Basalt High School, recommended explicit mentions of climate change in the elementary grades become actual standards.

He said he grew up fishing, backpacking and skiing. “I want my kids to grow up on a planet that isn’t on fire!” he wrote to the board. “The younger generation must be equipped with a proper education in order to tackle one of the largest issues the world has ever faced.”

A sophomore at Fairview High referred to the devastating impacts of climate change on the 2013 flood and the Marshall Fire. The student recommended that all grades should identify a local climate problem and propose solutions. Others wanted to see the societal benefits of transitioning to renewable energy.

Turning climate anxiety into positive action

Last year Colorado youth successfully lobbied state lawmakers to establish a Seal of Climate Literacy. The law allows school districts to offer a special seal or endorsement on a high school diploma that recognizes students who have achieved climate literacy. Students complete a high school science class and another course that touches on issues related to climate change as well as a hands-on experiential project.

Studies show environmental action is an antidote to climate anxiety.

In May, students in graduation gowns from Alameda International Junior/Senior High proudly put on Seal of Climate Literacy medallions and a special green sash around their necks. They were among the first cohort of students to earn the new seal.

“It’s definitely an honor,” said Alexander, 18, who said he appreciated being able to learn about how environmental challenges affect the cost of living and people’s health. This year he’s employed in the army as a mechanic but has an interest in renewable energy.

Students monitored city river water — testing pH levels, alkalinity, and oxygen levels. They learned about the river’s ecosystem and watershed health. Jaylene, 18, said the experience changed how she sees the world.

“It makes me want to help out the environment more.”

This year, Alameda International students will be able to take a river science class and earn ecology and water quality certifications.

“What we've learned in working in communities all across the state is that students are ready to take action around climate, and it's the rest of us that need to follow along with them,” said Elizabeth Harbaugh, vice-president of Lyra, an education nonprofit that helped spearhead the Seal of Climate Literacy. It helps school districts, particularly in rural Colorado, with climate education and how to be more climate resilient.

Harbaugh said student advocacy on climate change is a critical part of combatting eco-anxiety.

“When students are able to have hands-on learning or are able to do things that make a direct impact on their community that they feel more empowered, they feel more confident and maybe more hope in the face of a really tough issue.”

Valarie, 18, said since she was small, she has loved nature.

“But now when I see about how the climate is changing, (affecting) the fish and the water and everything … I was so excited about (the opportunity) to take care of the water, of the air because you know, we're living here.”

All of the Alameda International students interviewed said they support the inclusion of greenhouse gas and fossil fuels terminology.

Valarie said students must learn about the reality of this world.

“It (climate change) is happening.”

New revisions will be considered at Thursday's meeting

After all the feedback, new language is now on the table for the board to consider. Whenever there’s a reference to burning fossil fuels as a cause of global warming, the words “and other factors” would be added afterward. This would mean teachers can talk about the role fossil fuels play in warming the planet but also “other factors.”

Another proposed revision would direct high school students to “evaluate or refine a technological solution that reduces greenhouse gas emissions and other human pollutants.” The standards currently say that students should evaluate a technical solution that reduces the impacts of human activities on natural systems — without calling out greenhouse gas emissions. The updated revision adds “geothermal energy” to an example of a technological solution.

In a section on environmental effects could include loss of habitat due to dams — the proposed revisions add “and wind farms.”

Aisha O’Neil, founder of the Good Trouble Climate Network, said the updated revisions introduce unnecessary uncertainty, “undermining the scientific consensus that climate change is caused by the burning of fossil fuels.” They will continue to lobby for the board to differentiate between climate and weather in third-grade standards and mention climate change explicitly in every grade after that.

Overall, however, she said passing updates to the standards “would be a remarkable win for Colorado students.”

If the state board approves revisions, school districts must implement them within two years.