Updated at 11:36 a.m. on Monday, November 17, 2025.

Rosalba’s voice grew quiet and quivered. She took a deep breath to compose herself mid-sentence when she was asked to talk about the accident that killed six workers at Prospect Valley Dairy in Keenesburg last week. The victims included a father and his two sons, one still a teenager. Rosalba and her own son work at dairies not far from there. So do other members of her family.

“It’s tragic because people come to this country to give their family a better life… Imagine how heartbroken that family is,” she told CPR News in Spanish. “In search of a living, a person doesn’t know if they’ll come home or not. Only God knows if they come back to their family or not.”

Rosalba has asked to not use her full name because she’s not just sad, she’s also scared. She left Guatemala and traveled to the United States a year ago to join her 21-year-old son and other family members working in agriculture in northeast Colorado. She is undocumented, which she says is the case for most workers at her dairy.

She’s here at a time when the U.S. president is trying to deport millions of people, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement has resumed raids on farms and dairies across the country. She’s fearful of speaking out, but after the tragic accident at Prospect Valley Dairy involving a suspected exposure to high quantities of the gas hydrogen sulfide, which is used in several industries, including agriculture, she’s also fearful for her own safety.

“If it happened one time, what’s to stop it from happening again in other dairies?” Rosalba asked.

She and other immigrant workers and family members also want to know if the deadly accident in Keenesburg could have been prevented.

Maria, who is from Mexico and also asked for anonymity given her immigration situation, works at a nearby farm and has been in Colorado working for 20 years. She’s a friend of Rosa Espinoza, the woman who lost her husband and teenage son at Prospect Valley Dairy.

“What can I say? There aren’t words for the pain she’s feeling,” Maria said.

Maria, Rosalba and others believe most people don’t understand how dangerous their work is, and they want more safety measures on the job.

Modern dairies ‘Got Milk?’ Yes. And hazards.

“They are not given the proper [safety] tools to work. That’s what I’ve heard from members,” said Lupe Lopez, an immigrant rights organizer with the American Friends Service Committee in rural Morgan County, which neighbors Weld County, where the six workers died. She questions whether the owners of the dairy did enough to protect their workers.

“If it was really important to you, you would have had the right tools, so this wouldn’t happen. They would have given their workers the proper training,” she said. “The victims here are the families and those who died. This is what makes me angry, because we are human beings and no one deserves to die like this.”

Lopez supports immigrant families as they maneuver through the years-long legal processes to gain work authorization and residency. She also has family working in dairies, farms, and meatpacking plants. She says she’s heard many stories from immigrant workers, and some of her own family members, about other close calls at dairy operations – times when toxic levels of gases sent workers to the hospital. Rosalba said that happened at her dairy just last week when a coworker accidentally mixed together chlorine and acid.

“He got dizzy and sick. We were in the same room milking, and we had to get out,” she said.

Besides strong chemicals used for cleaning milking machinery, there’s the danger from the large animals themselves. Rosalba says workers get hurt when moving 1,200-pound cows in and out of corrals and stalls.

“We run the risk of having a foot or hand broken. Since we don’t have any insurance, they send us home to rest,” she said.

A bad injury could leave a worker unemployed – or worse, as was the case at Prospect Valley.

The suspected deadly gas

The bodies of the six deceased workers were recovered on August 20 by emergency responders in a confined space in the dairy.

They included four members of the same family: Alejandro Espinoza Cruz, 50, of Nunn, along with his sons, 17-year-old Oscar Espinoza Leos, 29-year-old Carlos Espinoza Prado of Evans, and his son-in-law, Jorge Sanchez Pena from Greeley. The other two victims were Ricardo Gomez Galvan, 40, and Noe Montanez Casanas, 32, both of Keenesburg. Information about their immigration statuses is not publicly available.

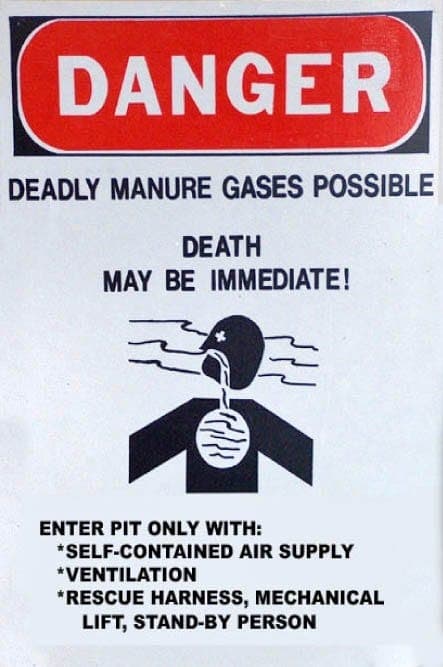

Dairy industry sources told Denver7 the confined space the workers were in was an underground manure pit, a space where decomposing manure produces gases that can be hazardous.

“When you’re dealing with a manure management system, there are four major gases of concern: ammonia, carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen sulfide,” explained David Douphrate, associate director of the High Plains Mountain Center for Agricultural Health and Safety at Colorado State University.

Douphrate said hydrogen sulfide, or H2S, is the gas most often associated with manure-related deaths. At a high concentration, it can cause rapid loss of consciousness and death within minutes.

Maria says, along with proper protective equipment, workers need training on how to handle such dangerous environments and what to do in an emergency. After the tragic accident, her son in the oil and gas industry told her about how his crew was trained to escape sudden toxic gas leaks. She believes the same level of training is needed at large dairies.

“All of us have family that work at a dairy farm,” she said. “Everything they do with toxic gases, it’s impossible for someone to (work) without protection because it’s so dangerous.

What protections should have been in place at Prospect Valley Dairy?

“Whenever you have a manure management system like what they have on large dairy operations, you have to account for [H2S]. You have to measure for it. You have to make sure and confirm that it is present, and if it is present at high enough concentrations, then you need to protect workers,” Douphrate said.

It’s not yet known what safety equipment and procedures were in place at Prospect Valley Dairy. Records show the dairy may have more than 10,000 cows. The dairy’s registered owner, Arend Bos, issued a statement over the weekend expressing condolences for the workers' families, but offering no explanation.

"We at Prospect Ranch and our employees are devastated by the tragic loss of our team members. While the cause is still under investigation, there is no indication that this is anything other than a terrible, isolated accident," the company said. "And, out of respect for the families and our employees, we will refrain from responding to the media at this point. We will continue to cooperate closely with local authorities. Our focus remains on supporting the families of those we lost and our employees."

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) says its investigation may take up to six months.

OSHA has permit standards for safety in confined spaces. Though for agricultural operations, they are only guidelines, so they’re not enforceable. Those guidelines include placing warning signs at entrances to confined spaces, testing for hazardous gases, properly venting the area, and having workers wear a safety harness so they can be pulled out of the space in an emergency.

Douphrate says workers in confined spaces should be supplied with oxygen masks. There are also sensors they could wear to alert them to the presence of H2S. According to dairy workers CPR spoke with, these types of protections are not commonly offered.

OSHA inspects dairies in Colorado, but it’s not clear how frequently those inspections occur. Of the more than 300 dairies here, according to a publicly available database, it appears only a few have planned inspections each year, and a few other dairies are inspected after a referral or complaint.

Prospect Valley Dairy was fined $8,000 by the EPA this year for a violation of the Clean Air Act.

It’s unclear if that violation is related to the same manure pit where it’s believed the six workers died, but it does demonstrate the industrial size of the dairy. The violation is related to specialized equipment installed in 2021 to turn emissions from manure into natural gas. The equipment appears to be part of a $50 million project with the nearby Lost Creek dairy and the Stellar J engineering contractor. According to Stellar J’s website, the project aims to pipe $20 million worth of natural gas to California each year.

How dairies could become safer

“These are not ‘Old McDonald’s Farm’ with sort of a small scale and small risks. These are large industrial facilities,” said Kelsey Eberly, an attorney at FarmSTAND, a national organization that advocates for better environmental practices and worker protections in the U.S. food system.

Since the 1970s, the average size of dairy farms in the United States has been growing. According to the USDA, large dairy farms with more than 1,000 cows now account for most milk production. This mirrors a trend seen in farming as the difficulties of the business force families to leave the industry, often selling their property to larger operators who can profit at scale.

Eberly is working with Colorado workers' rights groups to try to protect a 2021 state law she believes is at risk of being repealed. She said agriculture industry lobbyists are trying to convince lawmakers to strip away provisions of the Agricultural Worker Rights Bill. They have already succeeded in part: This year, state lawmakers removed a protection that allowed immigrant workers to meet with “key service providers,” such as medical personnel, attorneys and clergy, on private agricultural property during off-hours.

Most other provisions in the worker rights bill remain intact, despite objections from farm owners, including the right for agricultural workers to unionize.

It’s estimated that at least 51% of dairy workers in the United States are immigrants, many of them without valid work authorization. Eberly acknowledges that unionizing may not be easy for workers who don’t have legal status and fear retribution and deportation. Still, she believes the law brings progress.

“It’s a step to try to provide some greater sense of security and some great protection,” Eberly said. “It is certainly a step in the right direction for bringing these workers out of the shadows.”

Eberly says another step toward better safety could be making the OSHA permit standards for confined spaces apply to agricultural operations.

“We do know that farming and agriculture is one of the most dangerous industries for worker safety,” she said, referencing U.S. Department of Labor data that shows agriculture remains the sector with the highest rate of fatalities, ahead of the construction, transportation and manufacturing sectors.

“These are not new risks. This is an incredibly dangerous industry, and so certainly workers should be provided the protective equipment and training necessary to work safely in those kinds of environments,” she said.

Douphrate, whose organization provides safety training to dairy owners in Colorado and across the country, agrees that dairies need more resources to improve safety. He stresses that even though American dairies are getting larger, 95% of them are still family-owned and operated.

Dairy owners know they and their family members face the same hazards as other staff, said Douphrate. They often call him after news of industry deaths to discuss his perspective on an accident and whether there is something they could do better at their own dairy.

“The industry itself is always looking for ways to improve what they are doing and how they do it,” he said. “We need to continue to partner with industry, with owners, with the state associations. We all need to work together to address these issues.”

A program in Vermont may provide a model for how immigrant workers can partner with dairy owners, retailers and consumers to advance safety. Eberly pointed to the Milk with Dignity program started by the Migrant Justice organization.

“Basically, retailers that purchase milk from Milk with Dignity farms, the farms have to abide by certain safety and worker protections that are monitored by the workers themselves,” she explained.

Working together to improve dairy safety may also involve getting lawmakers in Washington to agree on immigration reform so that a well-trained workforce can be consistently maintained. The Dairy Farmers of America says dairies are facing a labor crisis, and they need “well-paid, dependable and skilled people” to work in an industry that is “uniquely demanding” and year-round.

The National Milk Producers Foundation (NMPF), which lobbies Washington on behalf of dairy farmers, says dairy workers don’t have access to the same H-2A guestworker visa program used to bring in seasonal workers for other agricultural work. The organization says dairy farmers struggle to recruit American-born workers despite higher wages. It warns that if they lose their foreign-born workers, it would disrupt farms and rural economies and raise the price of milk.

Immigrants feel their work is taken for granted

Rosalba has seen firsthand how her diary struggles to retain workers.

“It’s not easy. There are other [workers] who stay only two, three days and then they leave,” she said. But some have been there for years. She’s not sure what her future holds, but she believes that she might leave if she could find a safer job.

Maria and friends have been organizing GoFundMe drives and other fundraisers for the victims’ families.

She says the current climate toward undocumented immigrants makes her feel even sadder about the tragedy at Prospect Valley Dairy. According to the Labor Department, Latino immigrants in the United States are more than twice as likely as other workers to die from a workplace accident.

“I would like the people who go buy milk, who go buy meat, who go buy vegetables, fruits, to know the reality of all the work that we do — those of us who don’t have documents — so that they can be well fed and healthy. We are risking our lives for them,” Maria said.

“It’s sad what’s happening now, that they take for granted all we do for this country. That’s what hurts, that they don’t realize how we sacrifice our lives for their well-being.”

Alejandro Alonso Galva, Juanita Hurtado Huérfano, and Tegan Wendland contributed reporting.

Editor's note: This story has been updated with a statement from the dairy owner and to correct the spelling of David Douphrat.