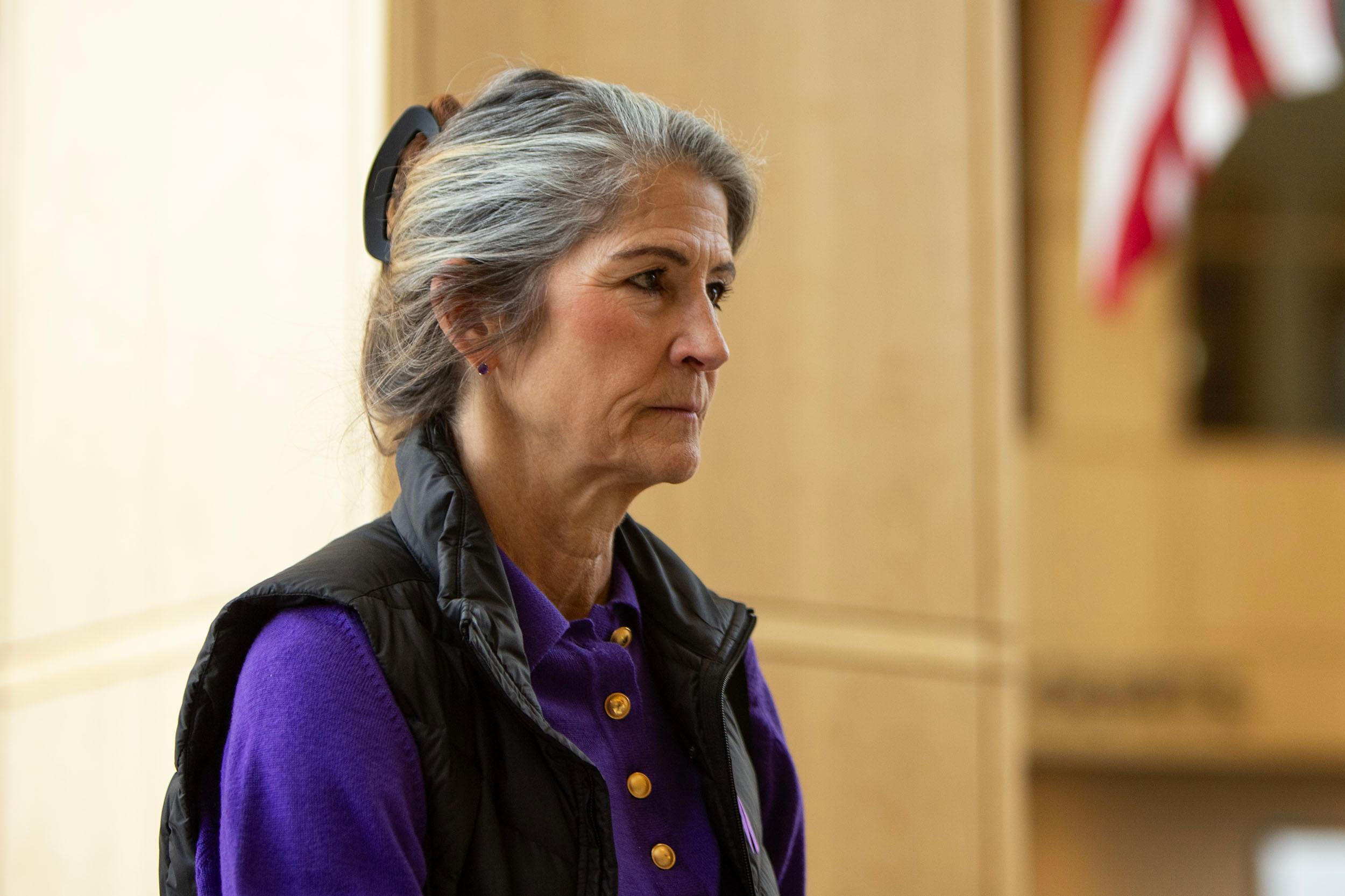

Marissa Garcia noticed a student at her Thornton high school was starting to miss a lot of school. But the girl had trouble connecting with adults. To the student, the thought of meeting with a school therapist was scary.

Over time, Garcia earned her trust — and gently encouraged the student to meet with the school therapist — walking her into the room and involving her mother in follow-ups.

It turns out the student had significant mental health issues.

“It was a relief to her,” Garcia said. “Something she always expressed to me is like, ‘I don’t know what’s wrong with me.’ Finally getting resources and answers helped the student feel some relief. "Now she is on track to graduate this year and seems much happier.”

Garcia, 24, a member of the Youth Mental Health Corps, wasn’t much older than the student at the time. That’s at the core of the program’s relationship-centered approach that relies on the unique trust teenagers place in someone just a few years older. Young adults 18 to 24 work in schools and other centers to help connect students to mental health and other support.

The program launched last year and early signs show schools with corps members reported fewer behavioral referrals, better attendance, and a cultural shift: More students now proactively seek out mental health support.

Colorado was one of four pilot states, with more than 140 corps members supporting 4,500 students in the first year. This school year the program is expanding from four to 11 states.

The “near peer” model

The model tackles two issues: a youth mental health crisis and a shortage of behavioral health professionals in schools. Nearly one in four middle schoolers report persistent sadness or hopelessness, and 17 percent say they have seriously considered suicide, according to the latest Healthy Kids Colorado Survey.

Vanessa Notman, associate executive director of Colorado Youth for a Change, the host organization for the Youth Mental Health Corps, believes the near-peer model has power.

“There’s a societal distrust of young people,” she said. “Having a program like this allows us to utilize the strengths of somebody who was not that long ago in the shoes of those students and can really relate to the things that they're experiencing in a different way than someone who has gone through seven years of school and has their Master's degrees and five years of experience.”

She stresses to corps members that they are not therapists or counselors. But they are a resource for the student to get information when they are struggling with their mental health or struggling to connect to school.

Corps members who commit to one year of service receive two weeks of intensive training and monthly professional development. They learn about trauma-informed care, case management, and Mental Health First Aid. Many also pursue credentials through the Community College of Aurora.

'I didn’t stop checking in with him'

Garcia is in her third year at York International High School in Thornton. She began as a member of Colorado Youth for a Change, which last year became the host organization for the Youth Mental Health Corps. Garcia was a nursing student when she switched paths during the pandemic, earning a degree in family and human development. She wanted to channel her own personal and life experiences into service.

As a corps member, she works with a caseload of 20 to 40 students, many of them absent about half of the time. She works to understand what the student is missing, “whether basic needs at home or if it's more behavioral health matters, maybe it's social emotional skills, or goal setting.”

Sometimes she provides resources to the family for transportation or food banks.

“My overall job is to make sure the students are not falling between the cracks and making sure that they're getting everything they need to be at school and then to be healthy individuals."

Garcia said many teens don’t have a consistent adult in their life and to young people, consistency is what matters most.

“I’ve had kids who took a year and a half for him to open up to me. Over that year and a half, I didn't stop shooting him texts…I didn't stop checking in with him.”

Garcia said she sees a lot of students unsure of what they’re feeling, not being able to control emotions. Garcia observes that instead of school staff immediately disciplining a student who is acting out, “letting the student breathe, talking to them about what they're feeling, can go a long way.”

Training for the future

The Youth Mental Health Corps also aims to boost the number of people getting mental health counselor certifications. Nearly 90 percent did last year. Twenty percent secured employment in behavioral health before finishing their service year.

Garcia earned her Behavioral Health Assistant certificate last year. But at 24, she is aging out of the program. She said it will be hard to leave the school. But she said the experience has reshaped her career path. She has applied for Master’s programs in social work. The corps gave her hands-on experience, a stipend and stackable credentials that can apply to more education in the future.

Lake Middle School case study

An evaluation report by the research group West Ed highlights central Denver’s Lake Middle School, where nearly 80 percent of students are Hispanic and nearly 90 percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. The report notes that challenges at school have been compounded by systemic issues that students face outside of school, including family incarceration, substance abuse and trauma.

More than 50 students received individualized support in the first semester last year from corps member Josiah Sanchez.

“I grew up in this neighborhood,” said Sanchez, in the report. “I know what these kids are going through. I want to be the person I wish I had—someone who shows up, who listens, who makes you feel like you matter.”

School officials said Sanchez was someone the kids could relate to. He could be arranging tutoring for a student, arranging for food or clothing assistance or mediating peer conflict. Students would seek him out during passing periods.

“They were asking around, trying to find him,” said one teacher in the report. “He’s doing something that’s winning their trust – that’s leadership.”

School administrators credit Sanchez’s daily presence with reducing behavioral referrals and improving absenteeism. More students began seeking out mental health support on their own.

For Sanchez, the program opened a path he hadn’t considered.

“This role has helped me find my own voice,” he said. “I’ve learned that my presence matters. Seeing these students try, seeing them show up—that’s a big success.”

The Youth Mental Health Corps was launched by Pinterest and the Schultz Family Foundation.