Dr. Pamela Valenza wasn't immediately alarmed by the construction outside Tepeyac Community Health Center.

The nonprofit clinic, where she works as the chief health officer, sits in the heart of Elyria-Swansea, a working-class and largely Latino neighborhood in north Denver. Her office is part of a larger redevelopment to convert an entire city block into brightly colored community spaces and affordable housing.

Until last summer, Valenza assumed the excavators were at work on the final phase of the project: a long-planned affordable senior living facility. But while scrolling on social media one evening, she caught a post revealing it was, in fact, a future data center.

“At the forefront of my mind was just understanding what would be the potential impacts to the surrounding community here,” Valenza said. “There's a lot of unanswered questions.”

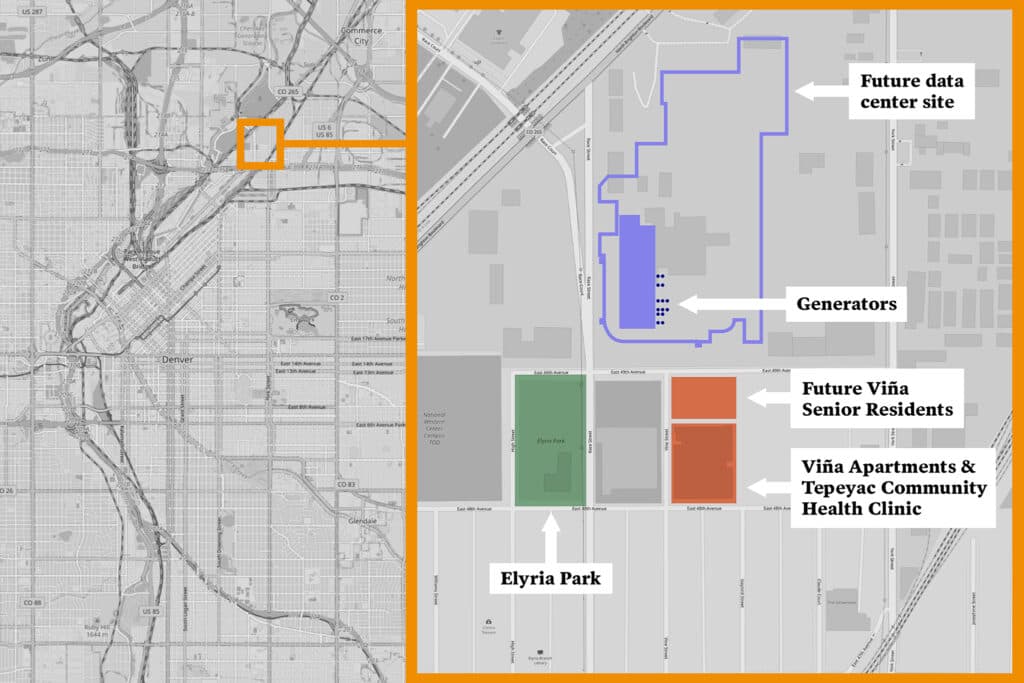

CoreSite, a Denver-based data services provider, is currently at work on a data center campus less than a block from the health clinic. The initial 180,000-square-foot building is scheduled to be fully operational by mid-2026. Once completed, the final complex will hold three facilities with 600,000 square feet for cutting-edge processors — computing power available to help corporate customers run cloud-based software or new AI tools.

The company claims the project will create 75 permanent jobs and generate more than $200 million in city property tax revenue over two decades. It also announced plans earlier this month to refresh a computer room at the local Boys & Girls Club and pledged to join with some of its suppliers to donate $25,000 to other local community groups.

Valenza, however, fears public health risks presented by the data center will outweigh any benefits to Elyria-Swansea. Besides her concerns about light and noise pollution, she’s learned data centers use fossil-fuel-powered backup generators to provide uninterrupted service during power outages. The CoreSite facility, for example, will rely on 14 diesel-powered generators positioned near the future affordable senior housing complex, according to planning documents.

Elyria-Swansea residents already worry about pollution from a nearby dog food factory and an oil and gas refinery owned by Suncor Energy. Along with other communities nationwide, it's now facing the possibility that the AI boom could leave residents breathing yet another source of urban air pollution.

A vulnerable, over-polluted neighborhood

The roots of heavy industry stretch back more than a century in Elyria-Swansea.

Starting in the 1870s, smelters refined heavy metals in the neighborhood, leaving a legacy of soil and groundwater contamination in a four-square-mile Superfund site. Major factories later arrived to benefit from railroads and highways crisscrossing the area.

In more recent decades, residents unsuccessfully fought the expansion of Interstate 70, warning that expanding the highway would be bad for air quality. The project was completed in 2023.

Those battles brought more attention to residents struggling to improve local air quality. A state-funded health study, conducted as part of a settlement over the I-70 expansion and published in February, confirmed the neighborhood’s asthma hospitalization rate is significantly higher than Denver’s average. It also concluded air pollution exposure likely contributes to higher childhood asthma rates in the area.

Julie Mote, a neighborhood resident, said pollution leaves a black film on her windows in Viña Apartments, the affordable housing complex above Tepeyac Community Health Center. She sees the data center as a continuation of Elyria-Swansea’s history: another industry putting a controversial project in an already polluted area.

“They do this kind of stuff in the poorer neighborhoods. Because this wouldn't go down a few blocks up. No way,” Mote said.

The project, however, caught the attention of local leaders after CoreSite applied for a $9 million sales tax break last year. A Denver City Council committee held a hearing to consider the plan in October 2024.

While the facility is far smaller than “hyperscale” data centers planned by tech giants like Meta and Microsoft, officials found its environmental footprint is still significant. CoreSite executives acknowledged electricity usage at the completed site would peak around 60 megawatts, more than the total power currently required to operate Denver International Airport.

Cooling data processors inside the first building alone will require up to 275,000 gallons of water per day, roughly equal to the average daily irrigation at some of Denver's larger golf courses. The fully completed site is expected to require up to 805,000 gallons of water per day.

Why some experts fear the AI boom could harm air quality

The meeting only briefly touched on any potential risk to local air quality. After one council member raised the issue, Erick Bromfield, CoreSite’s vice president of acquisitions and development, denied that data centers produce significant amounts of air pollution.

“We're not really too different from a big office building, 99% of the time,” Bromfield told the committee.

CoreSite noted that the facility would rarely operate at full capacity, but the water and electricity figures still alarmed officials like at-large Councilmember Sarah Parady, who told CPR News she “could not see the logic of giving a tax credit to that kind of user.”

The company dropped its bid for tax benefits a few weeks later.

It’s true that most data centers — including CoreSite’s project in north Denver — look like nondescript warehouses lacking visible smokestacks.

Unlike other industrial sites, the facilities are also linked to customers via fiber optic cables, not trucks or trains, known to belch exhaust. The facilities, however, demand vast amounts of electricity from a grid heavily dependent on fossil fuels.

Some utilities have cited data center growth to justify delaying the closure of fossil-fuel power plants nationwide, according to a recent report published by climate advocacy organizations Environment America and Frontier Group. Other power companies are planning new gas-fired power plants to meet data center demand.

Backup generators also represent a potential local pollution source. Diesel-powered systems release significant amounts of dangerous particulate matter and nitrogen oxide. President Donald Trump’s Department of Energy has also warned that blackouts could become far more frequent by 2030 — unless the country powers future data centers with new and existing fossil fuel power plants.

Potential costly damage to climate and air

Multiple studies have investigated how the situation could accelerate climate change. The AI boom will also have local and regional environmental impacts, according to Shaolei Ren, an associate professor of engineering at the University of California, Riverside.

“Air quality is one of them,” Ren said.

Ren co-authored a study on the topic published by UC Riverside and Caltech last year, which is under peer review before it’s published in an academic journal. The research found data centers could result in as many as 1,300 premature deaths every year by 2030 due to air pollution linked to cancers, asthma and other diseases. The public health costs could also climb higher than $20 billion annually as residents seek treatment and miss work due to their illnesses.

Major tech companies like Google, Microsoft and Meta claim the study results exaggerate the potential health impacts. In an article by the Financial Times, the companies said the researchers overestimated how much data centers rely on their backup generators and failed to account for their investments in renewable energy.

Ren, however, said investments in solar and wind can’t offset the risk of local pollution. During blackouts, he said, diesel exhaust from generators could overwhelm communities surrounded by data centers. In addition, some facilities have requested to use their backup generators to avoid overtaxing the grid during moments of high energy demand, like hot, sunny days when nearby residents run their air conditioners.

To guard against those scenarios, Ren thinks the AI industry should rely on a simple tactic: putting data centers far from vulnerable communities.

“To minimize the overall health impact, we should do the health impact analysis first and then try to find the locations that are not so harmful in terms of public health,” Ren said.

But companies like CoreSite have opted against that strategy in order to install AI services close to their future customers.

How CoreSite chose north Denver

CoreSite currently operates two other data centers in downtown Denver and North Capitol Hill.

It chose Elyria-Swansea due to its proximity to those existing facilities. Shorter distances allow the company to cut lag time for its future customers in the Denver area, who expect AI-generated responses as quickly as possible, according to Megan Ruszkowski, a CoreSite spokesperson.

“The location was one of the few undeveloped, available parcels in the city that is properly zoned for such a project. The site is in close proximity to current and prospective business customers,” Ruszkowski said in written responses shared with CPR News.

Property records show CoreSite bought the site for $33.5 million in 2022. It previously served as a concrete manufacturing plant, but state air quality records indicate the facility ceased operations at some point after 2018.

The location is also surrounded by other industrial sites, such as an auto repair shop offering diesel emissions testing for heavy-duty vehicles. Ruszkowski said those facilities run diesel engines far more regularly than the future data center, which is only allowed to use the 5,040-horsepower engines during power outages or for brief testing runs between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m.

Those restrictions are spelled out in an air pollution permit issued by state air quality regulators last July. The document also sets strict fuel, hour and emission caps, and explicitly bans the company from running the generators to limit its electricity expenses — unless it installs cleaner generators and applies for an additional permit.

The generators also face inward toward the property, rather than the surrounding neighborhood. The company determined the placement based on wind studies, noise considerations and aesthetic impacts to the surrounding neighborhood, Ruszkowski said.

Those considerations, however, aren’t enough to reassure Ana Varela, a Elyria-Swansea resident and organizer with the GES Coalition, a local advocacy group. CoreSite held community meetings about the data center project in June and October 2024. In the later meeting, Varela said the company didn’t fully address concerns about health impacts like light, noise or air pollution.

Community organizers sent written follow-up questions afterward. In response, the company told residents the data center would “meet all zoning and air quality requirements” and claimed the backup generators wouldn’t run “often” since it expected reliable electricity from Xcel Energy, Colorado’s largest utility.

Varela wasn’t surprised the company didn’t offer more information. Going forward, she’d appreciate it if CoreSite held regular meetings with local residents or even installed fenceline air monitors to track pollution. But she doubts it would take those steps.

“This community deserves so much more. We deserve to be treated like any other gorgeous, historic neighborhood in Denver,” Varela said.

ABOUT THE 'WIRED, WIRED WEST' PROJECT

Data centers are booming across the Mountain West as big tech moves to solve its AI storage problem. Nondescript, square, warehouse-type buildings are popping up in neighborhoods, open plains, and rolling foothills. The burgeoning industry leaves many communities grappling with the prospects of increased air pollution, dwindling water supplies, and higher utility bills. All this even as climate models predict more heat, drought and other weather extremes across the Mountain West.

Read the entire series here.

This story was produced as part of a series in collaboration with The Mountain West News Bureau, which includes public media stations in Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, along with NPR.