Updated at 10:30 a.m. on Nov. 26, 2025.

For more than 200 years, Farmers’ Almanac has helped people decide when to plant their crops, go fishing and efven potty train their children — all guided by a blend of folklore and early weather predictions based on the phases of the moon and seasonal cycles. Now, that era is coming to an end.

“The Almanac had a pretty large influence around 100-120 years ago,” said Todd Ballard, agronomy specialist with CSU Extension in Mesa County. “But it’s been fading for quite some time now as more science-based information has become available.”

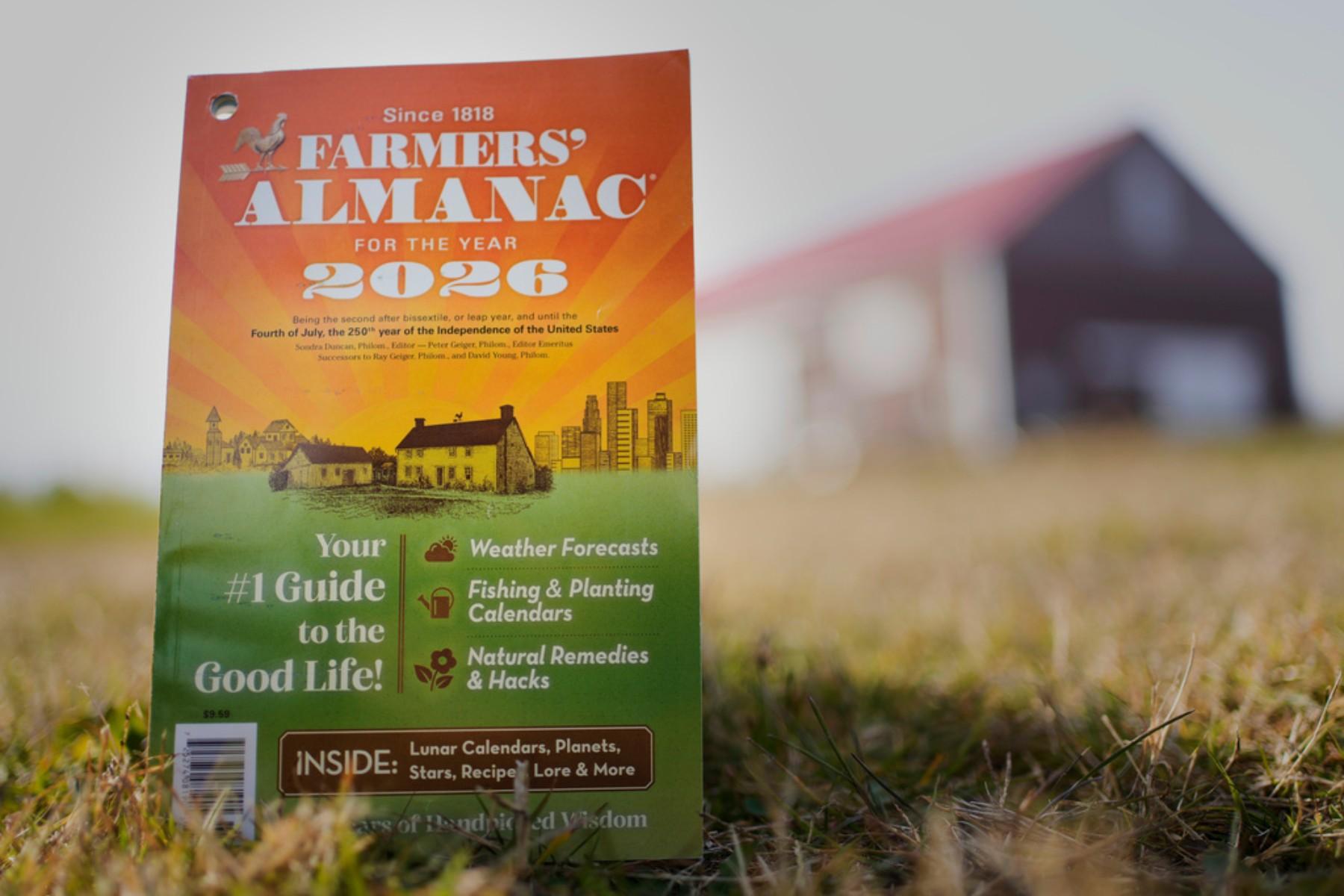

Almanac editors Sandi Duncan and Peter Geiger announced this month that the 2026 edition of the long-running print publication will be their last. In their farewell letter, they thanked generations of readers for “keeping the spirit of the Almanac alive” and encouraged people to continue planting “peas when the daffodils bloom” and watching “for a red sky at night.”

The announcement should not to be confused with the Old Farmer's Almanac, which was founded a couple decades earlier in 1792 with its famous yellow cover. The two made up one of the oldest publishing rivalries in American history — the original Time versus Newsweek, Coke versus Pepsi, Nike versus Adidas. (The two publications even disagree on where to put the apostrophe.)

Ballard said the Farmers' Almanac was once a vital resource in an era when long-term forecasts and soil data weren’t easy to come by, but it was ultimately anecdotal. “Anecdotes are certainly of value,” he said, “but they’re more a point where you start formal inquiries rather than being your final decision.”

Today, farmers and gardeners can find far more accurate information online. CSU’s Colorado Climate Center, for example, works with NOAA and maintains statewide soil and temperature networks, something that’s helpful when producers and home gardens alike are preparing to start their spring seedlings.

“The Almanac is printed long before planting season begins. Now there are websites, blogs and even YouTube channels that have more updated information,” said Ballard.

The publication itself claims 80 percent accuracy, but a 2010 study by the University of Illinois found its accuracy rate to be closer to 52 percent. Ballard pointed out that climate change has made traditional long-range predictions like those found in the Almanac more difficult.

“Anytime you add energy to a system, you make it more variable,” said Ballard. “The quick analogy I like to make is placing a pot of water on a stove — when you first put it on, it’s really a pretty calm pot of water. But as you heat it, boiling starts with small bubbles at first, and then when you get a rapid boil, it’s the most chaotic, unpredictable system.”

He said the same holds true for Earth’s atmosphere. “As you inject more energy through climate change, it will become more difficult to predict over the long term.”

For home gardeners in Colorado, Ballard said there are still some local traditions worth holding onto — even if they aren’t exactly scientific. “Here in Mesa County, the traditional anecdote is whenever the cross of snow on Grand Mesa is broken from the melting, then it’s time to go ahead and start planting your corn,” he said with a laugh. “There are probably many local things like that around the state that could still hold true.”

Overall, though, he recommends a more scientific approach when it comes to planting, like CoAgMet, Colorado’s Mesonet network, for up-to-date soil and weather data.

Ballard said the loss of the Almanac could be a reminder to Coloradans to get out and discuss the weather and planting more with their neighbors. “Go to the co-op and grab coffee, or go to your local diner and talk to your neighbors about the seasons. I think that’s really where we can have the human connection more than through print media, which is becoming less common.”

Because of this and the wealth of easily accessible information tied to all things weather, Ballard does not believe anything will rise to replace the Almanac. Its website, however, will remain online through December 2025, and copies of the final edition are available now at retailers like Walmart and Amazon.

Editor's Note: We added a graph avoid confusion between the Farmers' Almanac and the Old Farmer's Almanac.