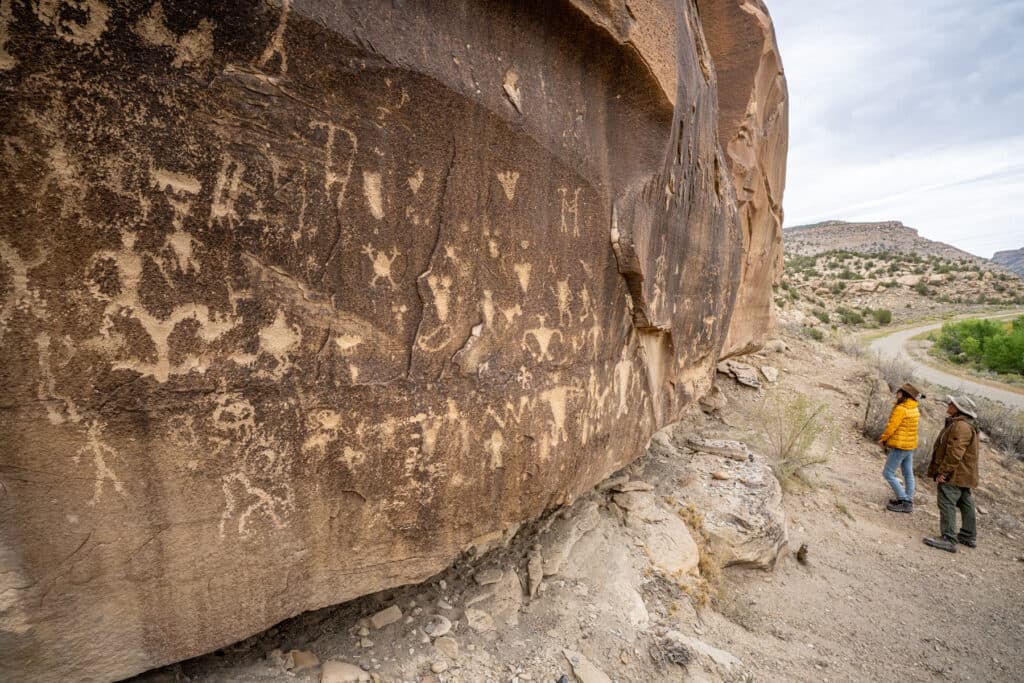

Staying awake for several days at the top of Ute Peak without food or water, after having the same dream four times, is part of the spiritual practice on the Ute Mountain Ute reservation in Southwest Colorado.

But you’d never know it by looking at the data collected by a recent survey of religion and who participates.

“We do traditional service here,” said Farley Ketchum Sr., a wildlife biologist who works as a technician with the Ute Mountain Ute environmental program. A leader of the tiny tribe in a rural part of southwest Colorado, he is also one of six traditional religious leaders on the reservation, whose population is between 1,500 and 2,000.

“We have a sweat lodge ceremony that I also conduct, and also we have Sun Dance religion here as well,” said Ketchum, who was willing to share general information about spiritual practices on his native land. “We’re pretty active in these traditional practices.”

While Christian, or Western religious practices are available there, a good portion of the reservation’s population practices more traditional religious beliefs, none of which showed up as even existing, according to the Religious Landscape Study, released earlier this year.

Done for the third time (previous studies were completed in 2007 and 2014) with a sample size of almost 38,000 people across the country, the Pew Research Center came up with only a handful of religious denominations that people surveyed said they took part in.

The survey found that about 62 percent of people in the U.S. are Christian. The two largest Christian subgroups are Protestant, at 40 percent, and Catholic, at almost 20 percent. Jewish adults were less than 2 percent, and Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus came in at about 1 percent each.

But the study didn’t capture the views of traditional Native American religions, practiced in a more quiet way without some of the pageantry and visibility of Western religions.

During an interview on the reservation, Ketchum, dressed in jeans, a sweat jacket and black office boots, was cautious about oversharing, as some facets of their spiritual practices are not talked about with outsiders. But he said the tradition of going to a church and sitting in a pew for a few hours on a Sunday morning isn’t the only option: sun dances and vision quests are ways of practicing that many community members hold sacred.

A sun dance, Ketchum Sr. said, is an all-night ceremony starting Saturdays at 9 p.m. that continues through the night until sunrise.

“There’ll be water drums in there and also a gourd and also the medicinal plant and they pray all night … Everybody has their own purpose for attending … to ask for help from the Creator,” he explained.

He was interviewed while sitting in a squeaky chair in his office, whose window looked out onto other tribal buildings, including a school where the Ute language was being taught, and a center where the community’s elders, some of them Ute speakers, went to socialize and receive services.

Ketchum said sun dances and other ceremonial practices are part of “traditional” religious practice, while religions examined in the study are what he and others on the reservation would consider “Western.” The traditional ceremonies practiced there were learned from Comanche and Cheyenne leaders from Oklahoma generations ago, he said.

“The sun dance is seeking power through the Great Spirit,” said Ketchum, 50, the father of seven, aged 9 months to 32 years, who took part in his first sun dance when he was 13. “We fast for three or four days without food and water … we seek this vision ... if we have problems, we enter it to get the answer how we’re supposed to go about this problem, this issue we’re having.”

He said during those ceremonies, children, noise and alcohol are prohibited, and they are for people who have had a specific experience: having the same dream four different times. When that happens, Ketchum said, they’d approach an elder for help deciphering it.

An elder, such as Ketchum himself, “would say, ‘What you need to do is you go to climb up this peak that is 10,000 feet, and you got to take no water with you. Take a tobacco pouch as an offering and sit up there without food and water and just meditate and get another vision up there. Then, when you receive that, then you get back down there.”

Ketchum’s vision quest was up Ute Peak. He said when he arrived with a pouch of tobacco, he tied it to the branch of an aspen tree. When he looked up, he could see other pouches of tobacco that had been left as offerings years before, tied to higher, older branches that went up toward the sky.

While on the mountain during a vision quest, Ketchum said, sleeping is not a big part of things. “Yeah, stay up as long as you can and get a little rest in, and continue until the early morning comes up. That’s the most important part, is the sunrise. You face east and greet the sun.”

A vision quest, as he described it, would often be the precursor for participation in a sun dance, he explained. Upon completion of such sacred ceremonies, he said, people tend to feel different. “You kind of feel, like, more wiser, that you’ve been through a lot within just that short time, and you kind of get a sense of a little bit of awareness. Your conscience is more stronger.”

Family members often offer praise to those who have completed a vision quest, but other people don’t necessarily know.

“The ones like your family, they know what you've accomplished, and they say, ‘That’s good.’ But it’s not for everybody to know,” he said. “It’s a personal experience for yourself. We make our own life, our own footsteps.”

Rather than using a spiritual book like the Quran or the Bible, traditional religion on his reservation isn’t written. “It’s kind of like oral, and it’s kind of private … something that we rarely share out of respect of the ceremony.”

And unlike other religions, where there’s an imam or a priest, he doesn’t have a title.

“They call me by my regular name,” he said.“They don’t give me no special title or treatment or anything. That’s not nothing to brag about. You just live, and the way you conduct yourself is the way they’re going to see you — how you are.”

The Pew Center would have loved to have included this form of practice in the Religious Landscape Study, which was conducted in English and Spanish from July 2023 to March 2024.

But not enough people from communities like Ketchum’s participated to have a statistical impact.

“If you wanted to get any sort of reliable estimates of a Native American religion as a group, you would probably have to conduct a specialized survey focused solely on that group ... we often don't have the sample size to give reliable estimates,” said Chip Rotolo, a research associate who participated in the study and interpreted the results.

But the number of Native people who follow a religious practice led by Native American leaders was less than one in a thousand — or smaller than one tenth of one percent.

“Out of the nearly 37,000 people who took this survey,” Rotolo said, “just 28 identified with a Native American religion.”