In late December, Xcel Energy shut off power to a vast swath of the Front Range, plunging Betty Devine and her best friend Beatrice Bell into darkness.

Devine has purple hair, a new look for the 69-year-old. It was a Christmas gift from Bell; the two had saved for months to splurge on each other.

“You know — you only live once,” she said of the new mane. “Why not?”

Devine and Bell share an apartment in low-income housing in Boulder. Their stretch of the city is decidedly urban — there’s a Target, Whole Foods and other big-box retailers nearby.

Even so, they lost power intermittently for four days because of exceptionally high winds and fire danger that blanketed Boulder County.

A lot of Devine’s energy went to keeping Bell comfortable in the dark. Bell has Stage 4 breast cancer, and now only occasionally leaves the house. Devine’s her caretaker — she’ll spend hours walking or taking the bus to pick up supplies and groceries to cook for her “sister from another mother,” as she likes to say.

Money is tight. After paying for rent and utilities, they have just $300 a month to pay for medicine, groceries and medical debt. Devine buys meat and seafood on sale, and carefully repacks and freezes it.

The outage spoiled nearly $200 in food, wiping out their reserves.

“Especially for us low-income people who sometimes struggle from month to month to make sure that we get all of our bills paid, it’s a real blow,” Devine said.

Public Safety Power Shutoffs are sometimes used by Western utilities to reduce wildfire risk during dangerous weather conditions. After all, it costs less to cut the lights than pay for the aftermath of another Marshall Fire, which caused around $2 billion in damages and resulted in a roughly $640 million settlement.

But shutoffs are a blunt instrument. After December’s event, businesses reported destabilizing losses, hospitals canceled visits, courts canceled hearings, and nursing homes gave notice that their residents were running low on oxygen.

The company has faced a torrent of criticism from Governor Jared Polis, Boulder’s city council and thousands of incensed residents, who’ve submitted comments to the Public Utilities Commission (PUC), which regulates Xcel.

On Wednesday, commissioners will hear directly from people affected by December’s shutoffs; Boulder is also holding a meeting on Thursday to brief residents about the city’s response. The PUC is in the early stages of crafting new rules around shutoffs.

But solutions to cut wildfire risk are not always fast or cheap, especially since fire season is now year-round. And in an increasingly dry climate, Colorado is poised to experience more shutoffs, a burden that will weigh heavily on people like Bell and Devine.

“It was a really upsetting experience,” Devine said. “Just the fact that we had nowhere we could turn to.”

Xcel said in a statement that its Colorado president, Robert Kenney, would be discussing the shutoffs at a hearing with state lawmakers this week.

Room for improvement

April 2024 was the first time Xcel pre-emptively shut off power. The utility said the move likely prevented a wildfire, but was criticized by residents and businesses.

The rollout “suffered from a lack of effective coordination,” according to state regulators, who vowed to improve how the company prepares the public for a shutoff.

A year later, Xcel, Boulder and other groups agreed to the utility’s sprawling, nearly $2 billion wildfire mitigation plan. The plan aims to reduce wildfire risk in Xcel’s territory and sets conditions for future power shutoffs.

Regulators required the company to improve how it communicates with customers, coordinate with emergency managers, and start a rebate program so customers with medical needs, like people on oxygen, can afford battery backups. It also required Xcel to work with towns to compile a list of “critical facilities” that need power, like hospitals or water treatment plants.

All of that work has started. But not all of it was finished when Xcel began its December 2025 shutoffs.

For one, dozens of towns haven’t finished working with Xcel on their “critical customer” list, according to a November update from the company. Those lists can help Xcel prioritize those locations for faster power restoration.

On Dec. 5, Xcel and other utilities held a tabletop exercise with emergency managers, to game out their response during a simulated shutoff. The timing — just under two weeks before Xcel cut the lights — was a coincidence. But the exercise highlighted the importance of proactive communication, according to Mike Alexander, the head of Douglas County’s Office of Emergency Management.

“I would certainly say that the management, and communication and end-to-end process between this particular PSPS that occurred recently, and the one in 2024, was greatly improved,” he said.

The company is also setting up its rebate program, which would pay for the entire cost and installation of a home solar system and battery. Xcel declined to provide a timeline on when the rebate would be available, and it’s unclear whether it would help renters like Devine and Bell.

'Not acceptable:' Boulder and Xcel share a rocky history

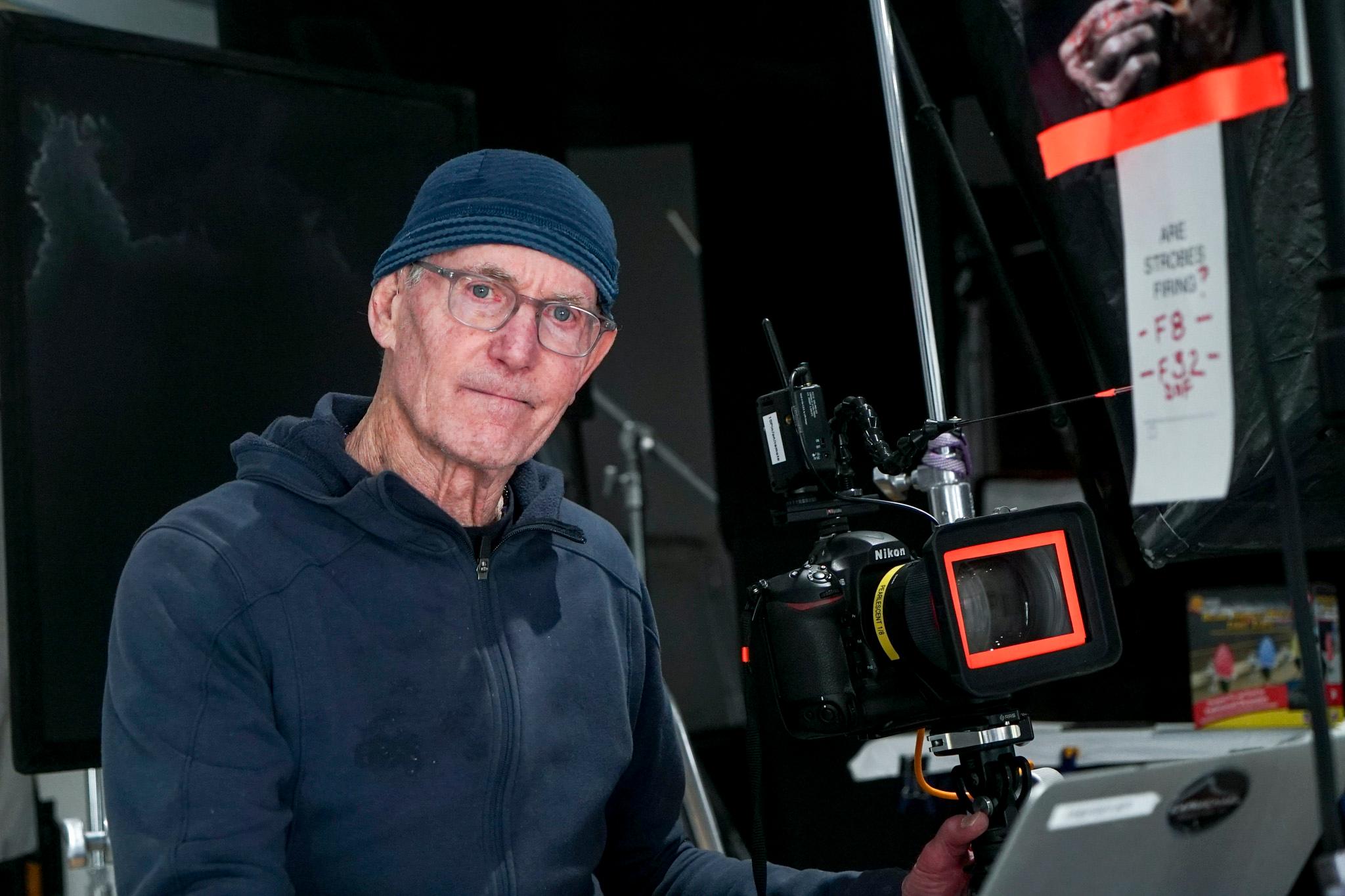

Boulder filmmaker Bob Carmichael has hauled cameras to the ends of the Earth and spent days dangling off mountains. He was an early pioneer in extreme filmmaking, but his shoots and outdoor pursuits required ample preparation.

Now 78 years old with rechargeable hearing aids, even he was caught off-guard when he lost electricity for days.

“ I've spent a lot of time in bivouacs and big climbs and all kinds of stuff, but I know what I'm getting into,” he said. “I don't just get thrust into it and say, ‘Good luck’.”

Carmichael choked up talking about the isolation he felt in the dark, during the shortest days of the year, and was incensed at the utility’s decision to cut power.

He’s not alone. The shutoff has opened old wounds in Boulder, a city that has tried and failed to sever itself from Xcel.

In the 2000s, Boulder residents began a campaign to start a municipal utility, like Colorado Springs or Longmont. It was an effort to force the company to use more renewable energy.

In 2011, Boulder voters approved ballot measures to move away from Xcel. In 2013, they rejected an Xcel-led petition that could have hamstrung the city’s efforts. With those victories, the city began the arduous process of actually starting its utility and buying out Xcel’s equipment, a crucial step. But that’s where the momentum faltered.

“[Xcel] fought it tooth and nail at every level — either refusing to provide information that the city needed, or being incredibly litigious,” said Steve Fenberg, formerly Colorado’s state Senate president, who was also part of the push to decouple Boulder from Xcel.

“Long story short — they bled the city dry,” he added.

Xcel declined to comment on its opposition to municipalization or Fenberg’s statements.

In 2020, Boulder backed off its quest to start a municipal utility, but got concessions from Xcel, which could benefit the city, according to their shared “partnership agreement.”

The company now pays the city a fee and has agreed to hit key benchmarks, like reducing local emissions, in exchange for being the city’s power provider.

If Xcel misses its targets, the city can exercise options to leave the agreement, which would be just one small step towards starting a municipal utility.

However, Xcel has already missed key emissions targets. In a letter sent to Xcel, Boulder’s city council said it had “major concerns” with the company’s progress, and tore into its communication during December’s shutoffs.

“It is simply not acceptable to turn off the power with the flick of a switch and then take four days to turn it back on,” the letter read.

Both Carmichael and the city council said the prolonged shutoffs may have more to do with avoiding wildfire litigation than protecting Boulder.

“ I don't think they did our town any great justice by turning off the power,” Carmichael said. “I think they may have avoided a calamity of their own.”

In a statement, Xcel said it appreciated the city’s feedback and remains committed to “advancing shared priorities while balancing affordability and reliability for all customers."

'Out of luck'

Among the hundreds of public comments submitted to regulators after the shutoff, many called on Xcel to bury more powerlines. That option eliminates the chance of a downed line sparking a wildfire.

But undergrounding is expensive. Xcel estimated it may cost more than $6 million per mile in mountainous parts of the state. Plus, those expenses are typically paid by customers in the form of higher energy bills.

While Xcel is burying some lines as part of its Wildfire Mitigation Plan, it’s being pushed by regulators to upgrade its aging grid with more modern solutions.

“The grid is not really set up for modern day,” Fenberg said. “It’s essentially the same grid that was installed a hundred plus years ago,” he added, alluding to the poles and wires that ferry electricity across the state.

State lawmakers have required Xcel to invest in “distributed” energy programs. For instance, Xcel is starting a “virtual power plant program” this year, which taps into customer batteries to move electricity around when there’s high demand. The same program could also be used to move some power around during outages.

Xcel is confident it can improve its power shutoffs, according to a January report by the company. That’s a relief for Bell and Devine.

Since December, Bell’s condition has taken a turn for the worse. Her doctor told her she has just a few months left to live.

She’s now on oxygen, which means she needs continuous power to run her compressor. The duo has four spare tanks, which would last just a day if the power goes out.

“ Knock on wood, we won't have another incident like this, while she's still here with us,” Devine said. “Because if the power goes off, then we're gonna be completely out of luck.”