One of the most common reasons for finding yourself in the emergency room is pain. In response, doctors may try something simple at first, like ibuprofen or a Tylenol. If that wasn’t effective the second line would be the big guns.

“Percocet or Vicodin,” says Swedish Medical Center ER doctor Peter Bakes, “medications that certainly have contributed to the rising opioid epidemic.”

Now though, physicians are looking for alternatives to help cut opioid use and curtail potential abuse. Ten Colorado hospitals, including Swedish in Englewood, participated in a six-month pilot project to cut opioid use called the Colorado Opioid Safety Collaborative. It was launched by the Colorado Hospital Association and is believed to be the first-of-its-kind in the nation.

The goal was for the group of hospitals to reduce opioids by 15 percent. Instead, Dr. Don Stader says the hospitals did much better: down 36 percent on average.

“It’s really a revolution in how we approach patients and approach pain, and I think it's a revolution in pain management that's going to help us end the opioid epidemic,” Stader says.

The decrease amounted to 35,000 fewer opioid administrations than during the same period in 2016.

The overall effort to limit opioid use in emergency departments is called the Colorado ALTO Project; ALTO is short for alternatives to opioids.

The breakthrough method calls for coordination across providers, pharmacies, clinical staff and administrators. It introduces new procedures, for example, like using patches for pain. Another innovation, Stader says, is using ultrasound to “look into the body” and help guide targeted injections for pain.

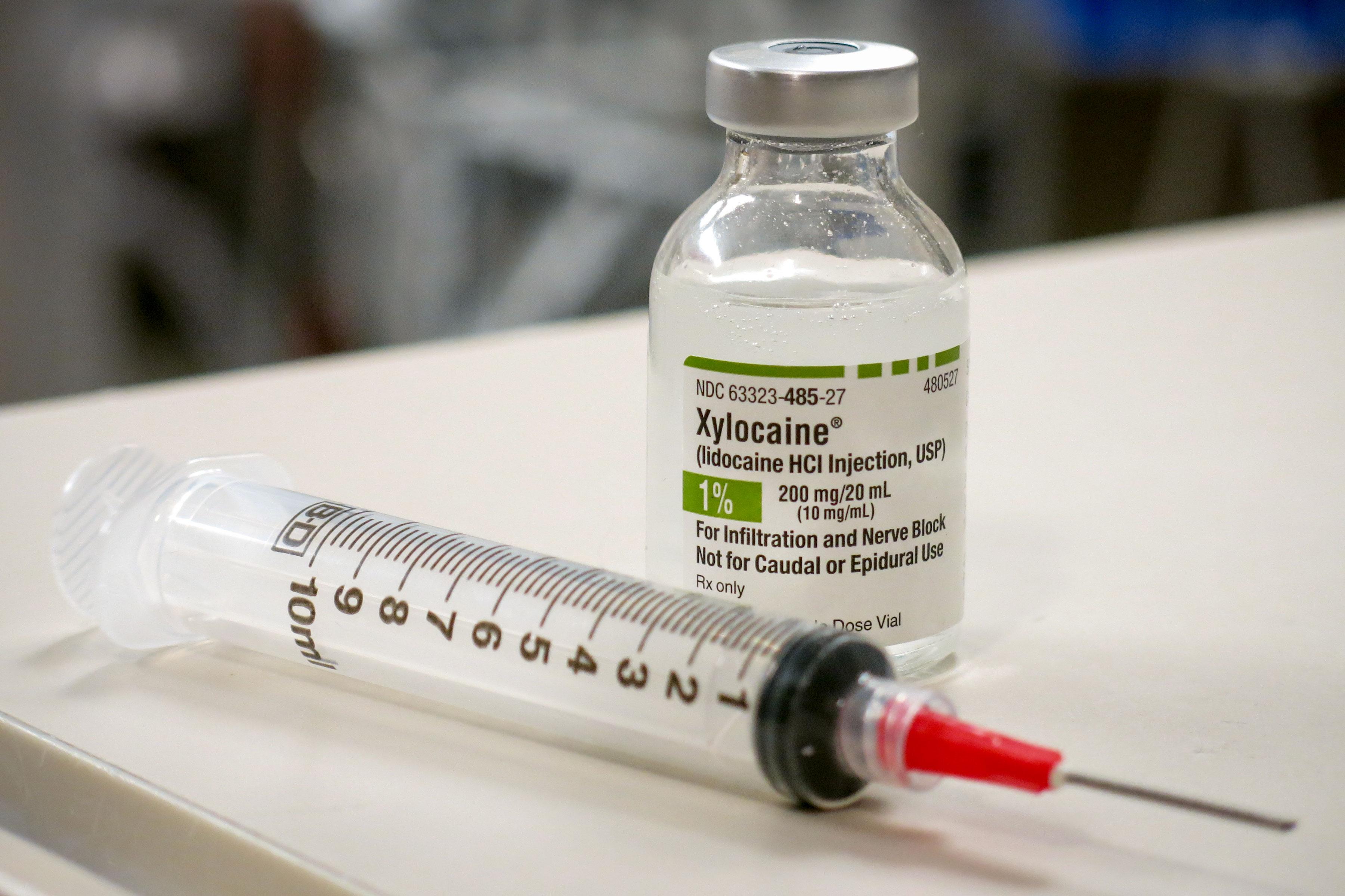

Rather than opioids like oxycodone, hydrocodone or fentanyl, Stader says safer and less addicting alternatives were used, like ketamine and lidocaine, an anesthetic commonly used by dentists.

Lidocaine was by far the leading alternative; its use in the project’s ERs rose 451 percent. Ketamine use was up 144 percent. Other well-known painkillers were used much less, like methadone (-51 percent), oxycodone (-43 percent), hydrocodone (-39 percent), codeine (-35 percent) and fentanyl (-11 percent).

“We all see the carnage that this opioid epidemic has brought,” Stader says. “We all see how dangerous it's been for patients and how damaging it's been for our communities and we know that we have to do something radically different.”

Claire Duncan, a clinical nurse coordinator in the Swedish emergency department, says the new approach has required intensive training. And there was some pushback, more from patients than from medical staff.

“They say ‘only narcotics work for me, only narcotics work for me.’ Because they haven't had the experience of that multifaceted care, they don't expect that ibuprofen is going to work or that ibuprofen plus Tylenol, plus a heating pad, plus stretching measures, they don't expect that to work,” she says.

The program requires a big culture change, encouraging staff to change the conversation from pain medication only to ways to “treat your pain to help you cope with your pain to help you understand your pain,” Duncan says.

Emergency medical staff are all too familiar with the ravages of the opioid epidemic.

They see patients struggling with the consequences every day. But ER doctor Peter Bakes says this project has changed minds and allowed health care professionals to help combat the opioid crisis they unwittingly helped to create.

“I think that any thinking person or any thinking physician, or provider of patient care, really felt to some extent guilty, but at least powerless to enact meaningful change,” Bakes says.

The pilot project has proven so successful that Swedish and the other emergency departments involved will continue the new protocols and share what they learned. Dr. Stader says the Colorado Hospital Association will help spread the word about opioid safety, and look to see it adopted statewide by year’s end.

“And I think if we did put this in a practice in Colorado and showed our success that this would spread like wildfire across the country,” Stader says.

The ten hospitals that collaborated on the project include Boulder Community Health, Gunnison Valley Health, Sedgwick County Health Center, Sky Ridge Medical Center, Swedish Medical Center, UCHealth Greeley Emergency and Surgical Center, UCHealth Harmony Campus, UCHealth Medical Center of the Rockies, UCHealth Poudre Valley Hospital and UCHealth Yampa Valley Medical Center.