History Colorado mostly focuses on artifacts from the past. But not today.

Assistant curator James Peterson is in downtown Denver hunting for current artifacts. In this case, signs homeless people display asking for help, like the one Jeff Goldberg is holding.

"I was wondering if there’s any possibility that you would have a sign that you are willing to sell?" Peterson asks.

Goldberg has lived on the streets for years. He agrees to sell, and Peterson gives him $20 for the sign and his story.

What Peterson is doing is part of History Colorado’s new approach to building exhibitions by involving the public. This process, called "Exhibit Underground," includes reaching out to people who are often ignored, like Denver’s homeless population.

"I really do feel honored that they share their stories with me," Peterson says.

To get more public input, History Colorado displayed collected artifacts for the proposed homeless exhibition at an event for young professionals.

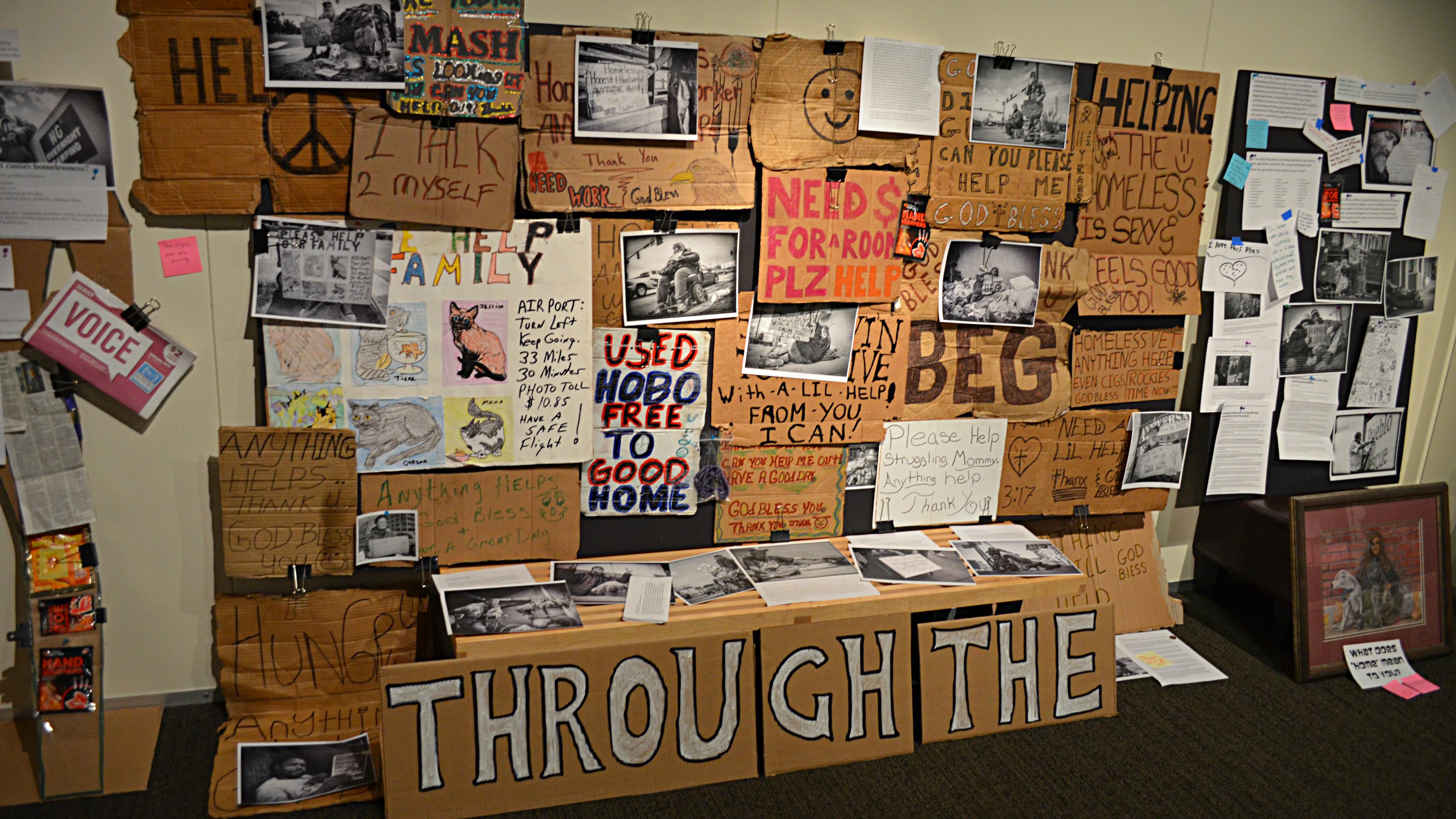

The 30 cardboard signs on display at the event say things like “Anything helps,” “Used Hobo Free to a Good Home,” and even “Helping the homeless is Sexy.”

The signs caught the eye of visitor Susanne Jayasanker of Centennial.

"Sometimes you get so used to seeing them, but you never see them in a museum so it definitely grabs your attention," Jayasanker says.

Museum curators ask the visitors for their reactions, including what home means to them. The input may be used to help museum officials decide what exhibitions move forward, and what shape they’ll take if they do.

After the event, the curators return the artifacts to the basement.

History Colorado Chief Operating Officer Kathyrn Hill points out other exhibition prototypes in the basement, including one on guns and one on Colorado’s Chicano history.

The museum has held several sessions with the public so far to generate feedback and ideas. Hill says including community members in the process is important.

"We need to be co-creating those exhibits with the people’s whose stories we are telling," Hill says.

She adds connecting the present to the past will make History Colorado’s projects more relevant.

"We need to be doing smaller, more ephemeral, more current exhibits," Hill says.

The homeless exhibition, for example, would not only include signs from the streets of today, but it also would include the museum’s collection of artifacts from one of Colorado’s most famous stories about poverty -- that of Baby Doe Tabor.

In 1883, a young divorcee, Elizabeth McCourt, better known as Baby Doe Tabor, married Leadville silver magnate Horace Tabor after he divorced his first wife. It caused a major scandal. When Tabor lost his fortune and died, Baby Doe lived in poverty. She ended her days in a one-room shack.

"Baby Doe’s story is the story of homelessness," Hill says.

The museum is now working to find ways to draw a strong connection between Baby Doe’s story and today’s issue of homelessness.

San Francisco-based arts consultant Kathleen MacLean says most museums are afraid to ask for public input. They see it as a threat to their traditional role as the arbiter of history. MacLean says History Colorado is embracing a powerful new way to create exhibitions.

"They’re kind of modeling the behavior for other museums," MacLean says. "Others see it can be quite powerful, quite thought provoking. And it’s so exciting, it’s contagious. Once people do it they really like it."

Other cultural institutions are starting to catch on to the idea. The 1960s section of the Oakland Museum of California’s History Gallery, called "Forces of Change," grew out of public input. McLean says more visitors leave comments about "Forces of Change" than they do about any other display at the Oakland Museum.

History Colorado is moving forward with one prototype developed through the "Exhibit Underground" process: Next year, input gathered on the state’s Chicano movement will be part of an exhibition on 1968.

Meanwhile the artifacts collected about homelessness are still in the basement.