Schechter spoke to Colorado Matters' host Ryan Warner.

Read an excerpt:

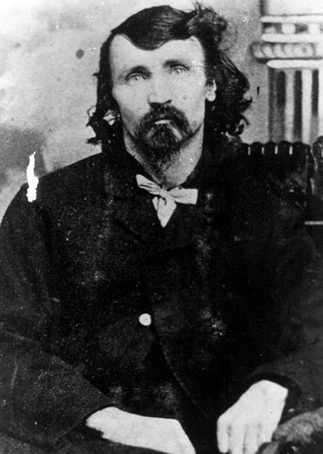

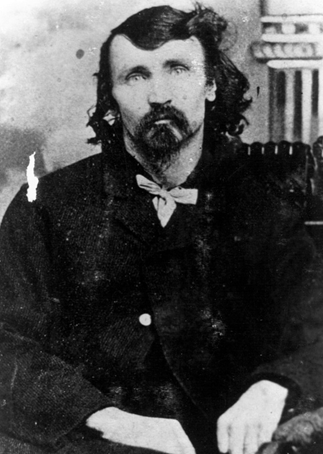

Part One: Deadman’s Gulch Asked to name the greatest explorers of the American West, most people—at least those with a modicum of historical awareness—would answer Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, Lewis and Clark had been largely forgotten by their countrymen, their achievements overshadowed by those of another trailblazer, John C. Frémont. Remembered today by few outside the ranks of professional historians, Frémont was hailed in his lifetime as “The Great Pathfinder” and “The Hero Who Started Civilization in the West.” One contemporary proclaimed that, along with Columbus’s first voyage to the New World and George Washington’s military triumphs in the Revolutionary War, Frémont’s deeds were “the greatest events in the world…connected with the rise and progress of the United States.”1 His renown rested on a series of surveying expeditions he undertook with the legendary scout and Indian fighter Kit Carson. In the course of these journeys, Frémont “covered more ground west of the Mississippi than had any other explorer,” mapped most of the Oregon trail, and played a leading part in wresting California from Mexico.2 The published reports of his adventures, packed with vivid descriptions and thrilling incidents, became instant bestsellers, inspiring thousands of settlers to migrate out west. Such was Frémont’s fame that, in 1856, he was nominated as the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate. The ensuing campaign was “one of the nastiest in the nation’s history.” Indulging in the kind of unbridled calumny that makes modern-day mudslinging seem like the height of civility, Frémont’s adversaries branded him “a secret papist” (a harsh accusation in an era of virulent anti-Catholic bigotry), a bastard, an adulterer, a native-born Frenchman, and the son of a prostitute. They also alleged that, during his last expedition, his men had resorted to cannibalism.3 Unlike some of the other imputations leveled against him, this one happened to be true. In 1848, at the behest of his father-in-law, US senator Thomas Hart Benton, Frémont—with three triumphant expeditions behind him— undertook a journey to chart a route for a transcontinental railroad. The proposed path, following the thirty-eighth parallel, would cut through the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan ranges of the Rockies, Colorado’s “roughest mountains.” Through urged by trappers familiar with the region to wait until spring thaw, Frémont and his party of thirty-three men forged ahead in one of the worst winters in living memory. Either through incompetence or (as some researchers believe) deliberate treachery, their guide, a sixty-one-year-old mountain man named “Old Bill” Williams, eccentric even by the standards of his breed, consistently chose the “worst possible routes.” Trapped in the snow-choked mountains, the men froze, starved, and began dying off one by one. After exhausting their food supply, devouring the pack mules, and consuming their own boots, belts, and knife scabbards, some survived on the flesh of their dead companions. In the end, ten of the thirty-three men perished in the disaster.4 Frémont failed in his presidential bid, losing the 1856 election to his Democratic opponent, James Buchanan. While other factors contributed to his defeat—among them his staunch antislavery stance— historians agree that the rumors of cannibalism associated with his “fatal fourth” expedition helped put an end to his political career. Twenty years later, in the same region of Colorado where the Pathfinder’s men suffered their harrowing ordeal, another episode of cannibalism occurred, inciting widespread horror in the American public. In contrast to the now all-but-forgotten Frémont, however— who had already begun his long slide into obscurity—its perpetrator would achieve lasting notoriety, becoming a permanent part of our national folklore. His name was Alfred Packer, though—as the West’s most infamous cannibal—he was known by a variety of epithets: Packer the Ghoul. The Human Hyena. The Man-Eater. Chapter 2: The New Eldorado On January 24, 1848, James W. Marshall, a transplanted New Jersey carpenter hired to construct a sawmill on the American River near Coloma, California, spotted some glittering flakes in the water. “It made my heart thump,” Marshall later recalled, “for I was certain it was gold.”1 Despite efforts to keep the find a secret, word of the discovery quickly spread, unleashing a worldwide epidemic of gold fever and instigating a mass invasion of California. The earliest arrivals found nuggets for the taking. Within a decade, however, the rivers were panned out. Disillusioned miners began searching elsewhere. In 1858, a party of prospectors led by a Georgian named William Green Russell turned up a few small deposits of gold dust in the Pikes Peak country of the Southern Rocky Mountains. Newspapers trumpeted the discovery, touting the region as “The New Eldorado.” Heeding the rallying cry of “Pikes Peak or Bust!” tens of thousands of treasure hunters swarmed to the Colorado Territory in the second-greatest gold rush in US history. Mining camps sprouted throughout the mountains. In less than a year, Denver grew from a small cluster of mud-chinked log cabins and ramshackle lean-tos into a bustling settlement with a population of close to five thousand. While most of the newcomers ended up with nothing but “broken hopes and busted fortunes,” some became rich overnight. “Millionaires were made in a matter of moments,” writes one historian, “as the born lucky swung their picks and felt the rock give way to…pay dirt—a pocket of mixed sandstone, clay, and quartz, impregnated with flour gold.” From a high-grade vein, a man could realize as much as $1,500 a day, at a time when the average American laborer earned less than one third of that amount in a year. The outbreak of the Civil War temporarily halted the stampede. With the war’s end, a new army of hopefuls flocked to the region. By then, the gulches and streams of the Rockies had yielded much of their precious yellow ore. Gold, however, wasn’t the only mineral treasure to be wrested from the mountains. In 1860—so one story goes—a prospector named Sam Conger, while camping on a meadow near Boulder Creek, fished out a nugget of silver from the water. Since Conger was hunting for gold, he attached little value to the specimen, though he kept it as a curio. Nine years later, however, after learning of the wealth issuing from Nevada’s fabled Comstock silver lode, he and some partners returned to the spot, where they quickly uncovered a rich vein of the precious white metal, setting off a second frenzied rush to the Colorado Rockies.3 From the older mining districts north of Denver, this new wave of fortune hunters poured over the mountains until it reached the mineral- rich wilderness of the San Juans. Situated in the southwest corner of Colorado, the San Juan country is an area of spectacular beauty, its towering peaks among the highest in North America, its slopes and alpine valleys heavily forested with native conifers and deciduous trees: pine, spruce, fir, cedar, aspen, box elder, and more. With its jagged peaks, deep canyons, sheer rock walls, and dizzying gorges, it is also a notoriously harsh environment, particularly during its prolonged, brutal winters. For John C. Frémont, whose fourth expedition met its terrible fate in the area, the San Juans were “the highest, most rugged, most impracticable, and inaccessible of the Rocky Mountains.”4 The natural obstacles presented by the San Juan range, however, did nothing to stem the tide of migrants. When one early pioneer, Enos Hotchkiss, uncovered a high-grade claim east of Lake San Cristobal, thousands of silver seekers swarmed to the area in a matter of weeks.5 The dream that possessed them was described by an earlier would-be miner “smitten with silver fever,” the young Sam Clemens. “I would have been more or less than human if I had not gone mad like the rest,” he recalled in later years when the world knew him as Mark Twain. “I succumbed and grew as frenzied as the craziest…I expected to find masses of silver lying all about the ground. I expected to see it glittering in the sun on the mountain summits.”6 For countless men lured to the “Silvery San Juans” by a similar fantasy, the quest for instant riches would end in abject failure. For a few, it would lead to something far worse. CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

|

Excerpted from Man-Eater: The Life and Legend of an American Cannibal by Harold Schechter. © 2015 by Harold Schechter. Published by Little A in August 2015. All Rights Reserved.