Jeremy Haley, a Denver business owner and entrepreneur, received a notice from the Drug Enforcement Administration on Aug. 30 that the natural substance he had been selling for nearly 5 years — first out of his home, then out of his storefront — would soon be considered more dangerous than methamphetamine.

“This is our freedom on the line,” Haley said. “If they make it Schedule I, technically they'll be treating it the same as heroin. And that could have me locked up in jail for life."

Less than a week after the DEA’s notice of intent to temporarily place kratom — a product made from the leaves of a southeast Asian tree — on the most restrictive tier of the Controlled Substances Act, Denver's Department of Environmental Health was at Rocky Mountain Kratom’s door.

Haley’s supply was put on a hold order. As a result, his business, which is one of the only kratom storefronts in the nation, was forced to close shop that same day.

"Given the fact that [the DEA] is framing this as pressing public health concern, and given our roles and responsibilities here as a local public health authority, we felt that it was our responsibility to address kratom products in the Denver markets," said Danica Lee, the director of public health inspections division for the DEH in Denver. Holds have now been placed on the kratom stock of 15 Denver stores.

The DEA says the reason behind the emergency scheduling is due to signs that kratom abuse is on the rise. The dried leaves are most commonly crushed into a powder, which can then be mixed with other liquids and drunk. It can also be brewed as a tea, or swallowed in capsule form. Across the U.S. there were 15 kratom-related deaths between 2014 and 2016, including one in Colorado. The Centers for Disease Control reports receiving 660 calls related to kratom exposure between 2010 and 2015.

Dr. Jeffrey Brent, a distinguished clinical professor of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, those numbers don’t seem overly concerning.

"Frankly, if they were unambiguous kratom-caused deaths, I'd be a little bit more concerned than these kind of mixed drug overdoses, or mix-drug usage where kratom might not have even been a particularity big player,” Brent said. “And it can be very hard to sort out with people with multiple substances."

He adds that the anecdotal accounts of users, who say it’s helpful for chronic pain management, overcoming depression and anxiety, and even weaning off opioids and alcohol, are just that — not necessarily reliable, since little research has been done. For comparison, the National Center for Health Statistics reports 18,893 deaths from opioid pain relievers in 2014 alone.

“[Kratom] is quite weak though, it doesn't cause a huge number of problems in most people,” Brent said. “But like anything else, all exposures to anything no matter what we're talking about is dose-dependent. And if you take enough, anything can make you sick and certainly that is true of kratom."

The DEA’s announcement to officially ban kratom was expected Friday.

"If it takes effect on Friday, you'll hear it. If it doesn't, you'll hear when it does," said Barbara Carreno, a spokesperson with the DEA.

She acknowledged the hundreds of calls and comments coming from users, adding that the response has been unexpected. The outcry from the community includes a letter from Congress, with the signatures of 51 representatives ― including 22 Republicans ― addressed to acting DEA administrator Chuck Rosenberg and asking the federal government to delay the scheduling of Kratom until further research can be done.

Colorado Democratic Rep. Jared Polis helped compose the letter.

"It is absolutely ridiculous,” Polis said. “The DEA to add kratom to Schedule I, along with marijuana, and say that both of them need to be controlled even more than opioids is ridiculous — when opioids are the devastating health crisis that so many families have faced and is causing so many deaths.”

He adds that banning kratom could make the opioid crisis worse, and that this decision would be “counterproductive.”

“I really worry that if it's allowed to go to Schedule I, some of those people might turn to opioids or harder drugs," Polis said. The letter was sent to the DEA on Sept. 28 and Congress has not yet received a response.

But the DEA’s silence doesn’t mean there is any change in plans to ban kratom, it simply means it hasn’t happened yet. Until they make the formal announcement, kratom remains legal.

Where does that leave Rocky Mountain Kratom? According to Danica Lee with the Department of Environmental Health, most likely right where they are now.

"If there was a change in the decision, we would certainly want to evaluate that before making a decision on action,” Lee said. “If the time frame is extended, but the result seems as though it will be the same, we would likely leave those hold orders in place."

For Jeremy Haley, the actions against kratom have only encouraged him to fight for the plant he says saves lives.

'Kratom Kingpin'

Haley first heard of Kratom while listening to a podcast. The guest of the show briefly mentioned his use of it for pain management. Haley started doing research and tried it for himself, and quickly found his anxiety and depression diminished, along with his cravings for alcohol.

"My life has been a 180 since then,” Haley said. “I was working in oil and gas at the time actually, and now I'm advocating for botanicals."

He says it helped him work the 16-hour days in the field, and helped him excel at his job. But in 2012, he was arrested for a DUI after a night of light drinking, and was caught with MDMA ― commonly known as ecstasy ― in his pocket. He lost his job and his right to drive, and moved back to Colorado where he is originally from.

"It's one of my biggest regrets in life, but it did lead me down this road,” Haley said. “And it pushed me towards seriously looking for better ways to live."

He continued to use kratom, and he says it kept away the urges to drink while on probation. That’s when he got the idea to start selling it.

"I had a feeling inside that people needed to know about this, and I needed to be the one to at least introduce it to people,” he said. “And to counteract the head shops that were selling it at the time, because a lot of the head shops are also giving kratom a bad name."

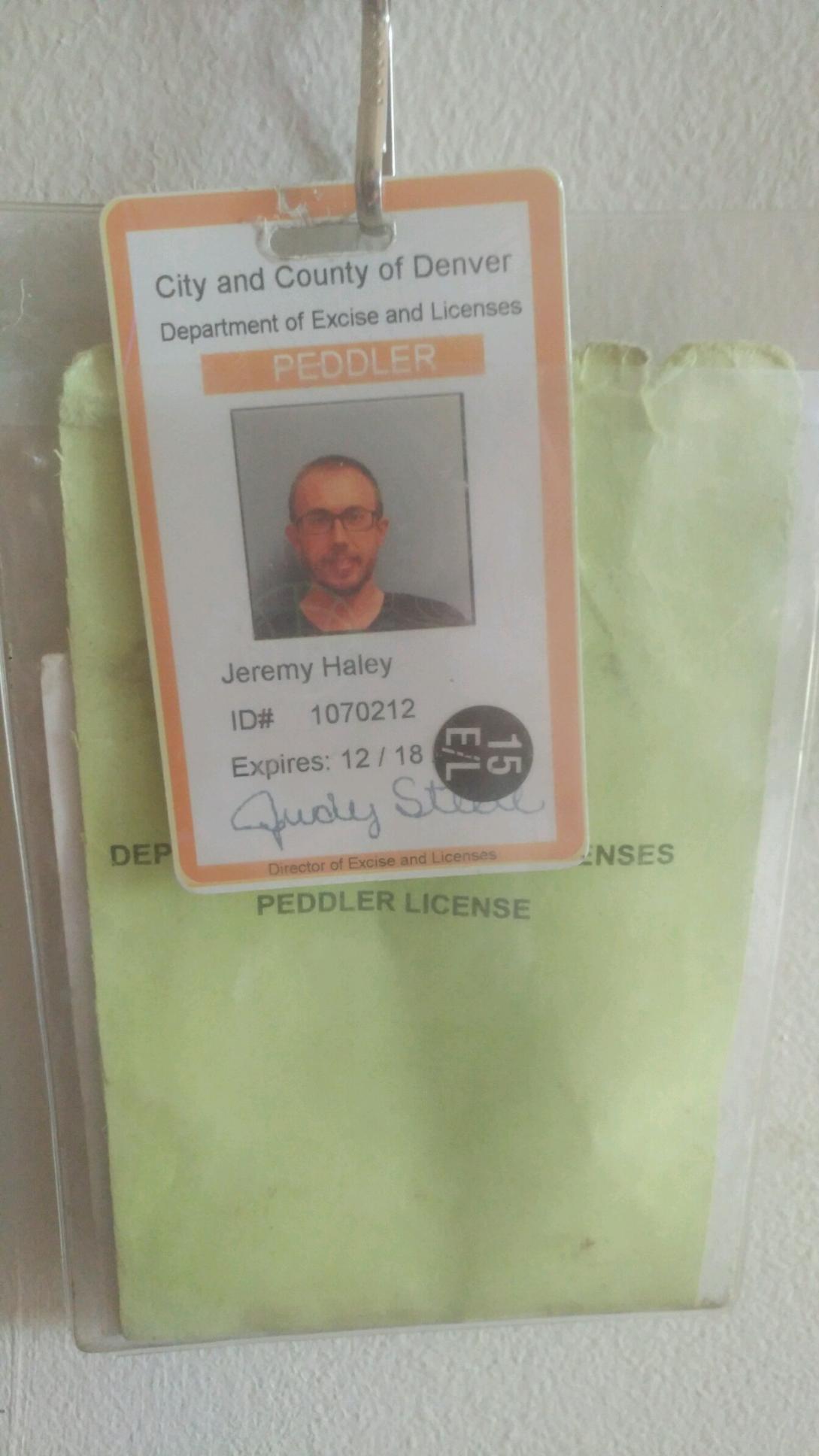

He applied for his peddler permit, and was allowed to sell kratom on the street. He set up a website and engineered it to be a top result after searching “opioid withdrawal help in Denver.”

"I'd walk out there with my big, goofy peddler's badge, and there'd be such a diverse group of clientele,” Haley said. “There'd be like, soccer moms and the elderly. I was really shocked by it actually at first. I kind of had my own personal stigma and idea of what kratom users, what the demographic would be.”

He admits he looked sketchy, with his brown paper bags and meeting people on corners. But he had to start somewhere.

“People were coming to me desperate, in really really rough situations. It was the only way I could figure out to make it work," Haley said.

He was even the subject of an undercover investigation by CBS4, and called a “street dealer.” He was worried what his probation officer might think.

“It was just kind of me flying solo there for a bit,” Haley said. “Which was a really cool experience, because it really let me dive in deep and meet a lot of the people and learn their stories and learn how much it's changed their lives in so many different ways and for so many different conditions, from multiple sclerosis to lupus, you can go on and on."

He continued selling this way for two years when he eventually saved up enough to rent out a space on Broadway.

"Things would start looking good, and then you would tell people what you're selling, Kratom, and then they'd Google it, and that CBS story would come up: 'Denver Street Dealer.' And then before you know it, no return phone calls or messages," he said.

But after a year and a half, business was pouring in.

"We were about ready to blow up,” Haley said. “We were on the verge of becoming a major business and opening many shops. Especially getting into wholesale was a huge goal of mine, and getting our product as accessible as possible in as many outlets as possible across the country for people to use it."

He said it probably would have taken off even faster if it wasn’t for the legal troubles his business has encountered.

"We were on the brink of getting shut down, and that's with amazing profits,” Haley said. “The profits didn't have anything to do with it. It's all the other loopholes, it really felt like playing some weird, twisted game."

Banks would close down his accounts because of what he was selling, and his product started being seized at customs after the FDA put out a notice saying that kratom was a substance of concern.

"The customs agencies felt like they needed to take some sort of action, in order to enforce that,” Haley said “And they seized hundreds of kilograms from several different vendors, not just us. And it's just thousands of dollars down the drain."

Haley had to get creative to keep the kratom coming in; he switched over to a Chinese shipping carrier, and had a lab perform tests on his product before it entered the U.S., to guarantee purity for the FDA. And all of it was labeled “not for human consumption,” something Haley had been doing since he started his business.

"It's pretty unfair, and it's always felt very gross having to put those disclaimers on there,” Haley said. “Because we obviously all know the deal. We were making like, kratom candles even. Just so we could keep our customers, you know, provide them the relief that they need. Because we've had so many that have been depending on this stuff."

He says that with all the troubles he’d already experienced, that he knew the DEA’s announcement was inevitable.

“I just didn't expect it to be this soon, or to happen the way that it did," Haley said.

He now sits in his yet-to-be-open shop on Broadway and Alameda, called Artisans Apothecary. It will focus on natural foods and supplements, and was supposed to be his new spot to sell kratom. It was scheduled to be up and running by Sept. 26, but he and his staff decided to focus their efforts on stopping the ban instead.

They flew to Washington to join the protest march on the capital Sept. 13, and they were inspired to put together their own event at the Denver capitol building. About 100 supporters showed up on Sept. 23, holding handmade signs, shouting “Kratom saves lives” and sharing their stories.

Many of the speakers at the event were customers of Haley's, including Jason Delapp ― a veteran from Colorado who was diagnosed with MS in 2005. Delapp found kratom and Haley after suffering from opioid dependency for 10 years.

“My wife and I had lost a daughter, 9 years ago,” Delapp said. “After that, we both used that pain even more than just physical pain and really abused prescription opiates."

He admitted that when it was tough to get the pills, it was easier to get meth and heroine, and he did both.

“That was probably self-esteem wise, the lowest point of my life ever,” Delapp said. “I drank when I was younger a little bit, teenager stuff. But I never did drugs. That wasn’t me.”

He says his wife got tired of their addiction, and found kratom as an option during her search for help. Delapp says he immediately saw a difference in her, and it convinced him to start using kratom himself. He’s now entirely off his medications.

“[Kratom] enables me to be in a good mood, and to think clearly, and to make good decisions with my MS to where I know if I've done too much," Delapp said. "The energy and mood alone makes it possible for me to be part of my families' life again, and I can remember it."

It’s people like Delapp that keeps Haley in the fight.

“I pray that we can all ban together and make our voices heard,” Haley said. ‘Even if it does get outlawed or made Schedule I, that we keep harping on [the DEA] and we do it the right way. Not angry phone calls or letters, or trying to tear anybody down. Because these guys are just trying to do their jobs too, and most of them are good guys. But we really need to make it heard that we're united, as a people. And we're not going to let our personal freedoms get taken away unless there's valid explanation at least for why they're doing this, and they have yet to do that so far."

Editor's Note: We reported there were more than 20,000 deaths from opiod pain relievers in 2014. That number is actually, 18,893. We also stated that the Department of Environmental Health was a state run department. It's run by the city of Denver. We regret the errors.