Ten years after the start of the war in Iraq, veterans are increasingly struggling with substance abuse, which often goes hand in hand with PTSD. A recent study shows that one out of five active duty service members say they drink heavily. As the numbers grow, so does the need for programs aimed at helping heal these invisible wounds. Haven Behavioral War Heroes Hospital in Pueblo started in 2009, bringing together staff with military backgrounds to focus on soldiers coming home from the current wars.

REPORTER SHANNA LEWIS: Patients at Haven don’t get much spare time. Sgt Rob Kennedy is one of the soldiers immersed in a full schedule of sessions that go all day long. The lean 28-year-old says he only drank once a month or so when he first joined the Army. But when he got back from Iraq the second time he’d changed.

ROB KENNEDY ohh - alcohol - I couldn’t sleep without it I couldn’t get up in the morning or start a day without it I was drinking every chance I had the opportunity too.

REPORTER: Alcohol made him feel more normal and helped quell the panic attacks that are part of his PTSD.

ROB KENNEDY…it’s easier to come back and just pick up a bottle then it is to ever admit that you have a problem that you’re in that much pain…..

REPORTER: But alcohol didn’t solve his problems - Kennedy tried to commit suicide. After that his family and other unit members pushed him to come to Haven. Four weeks at Haven is no easy task.

RACHEL LENTZ: We have them talk about the stuff they don’t want to talk about and remember the stuff they don’t want to remember.

REPORTER: Retired Air Force major Rachel Lentz is the clinical director at Haven. She’s part of the team that helps the 30 or so patients learn to deal with their PTSD and chemical dependencies. The therapists are nearly all former military personnel, which means they understand where their patients are coming from. Especially during the part of the program called exposure - where they go to places that trigger flashbacks for them like open spaces at the city park or a crowded Walmart.

LENTZ: ...we basically have him stand there and engage with whatever it is and talk about it and think about it and stay grounded in the present so that we can start to help them train their brains a new way of reacting to things because what they did when they were deployed it's very effective and reactive kept them alive but here it’s just causing problems ....

REPORTER: Haven medical director Dr. Harry Silsby is a Vietnam vet. He draws a diagram of the brain and explains to each patient what happens in the body when the fight or flight response is activated by threats or other stress.

HARRY SILSBY:... blood goes to your major muscles so you can run or get out of there, your eyes dilate, you quit digesting your food, you're hyper alert you can't sleep and after a while the more you're in trauma the more this thing starts going off and pretty soon goes off on its own.... I do this because I want them know that they aren’t crazy....this is sort of a normal reaction of the nervous system to an abnormal situation but it accounts for most of the symptoms that these guys have.

REPORTER: Patients learn how to recognize and control these physiological and emotional responses to stress. They have to deal with substance abuse issues too. Chemical and alcohol dependency are so intertwined with PTSD and other conditions that they can’t really treat one without treating the other. Not only that, some patients may need to quit medications that have been prescribed for them to treat PTSD, depression or pain.

SILSBY: Even though drugs will help these guys’ anxiety but they won’t learn to deal with it unless they can feel it.

REPORTER: Silsby started Haven because he saw that veterans could help others heal the invisible wounds of war. Sgt. Rob Kennedy wants to help others to face their problems too. When he’s retired from the service he wants to get a masters degree in social work and teach others what he’s learned at Haven. And it’s likely he’ll have plenty of work to do. Recent estimates by the Institute of Medicine show that well over half of the military members and veterans who need mental health care are not getting it.

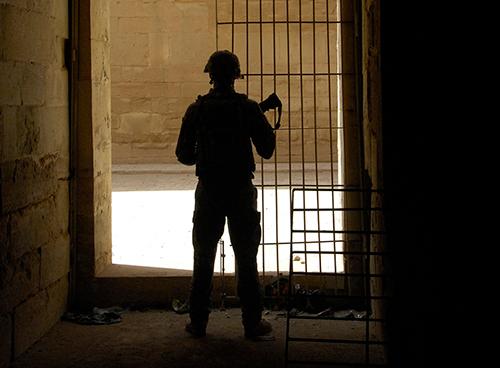

Photo:[PFC Sarah De Boise]