Kids at one summer camp in Boulder don't need swimming suits or hiking boots. New ideas and a whole lot of curiosity are much more important for a science summer camp at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Here, kids do work that mimics sophisticated research taking place at university labs just down the road.

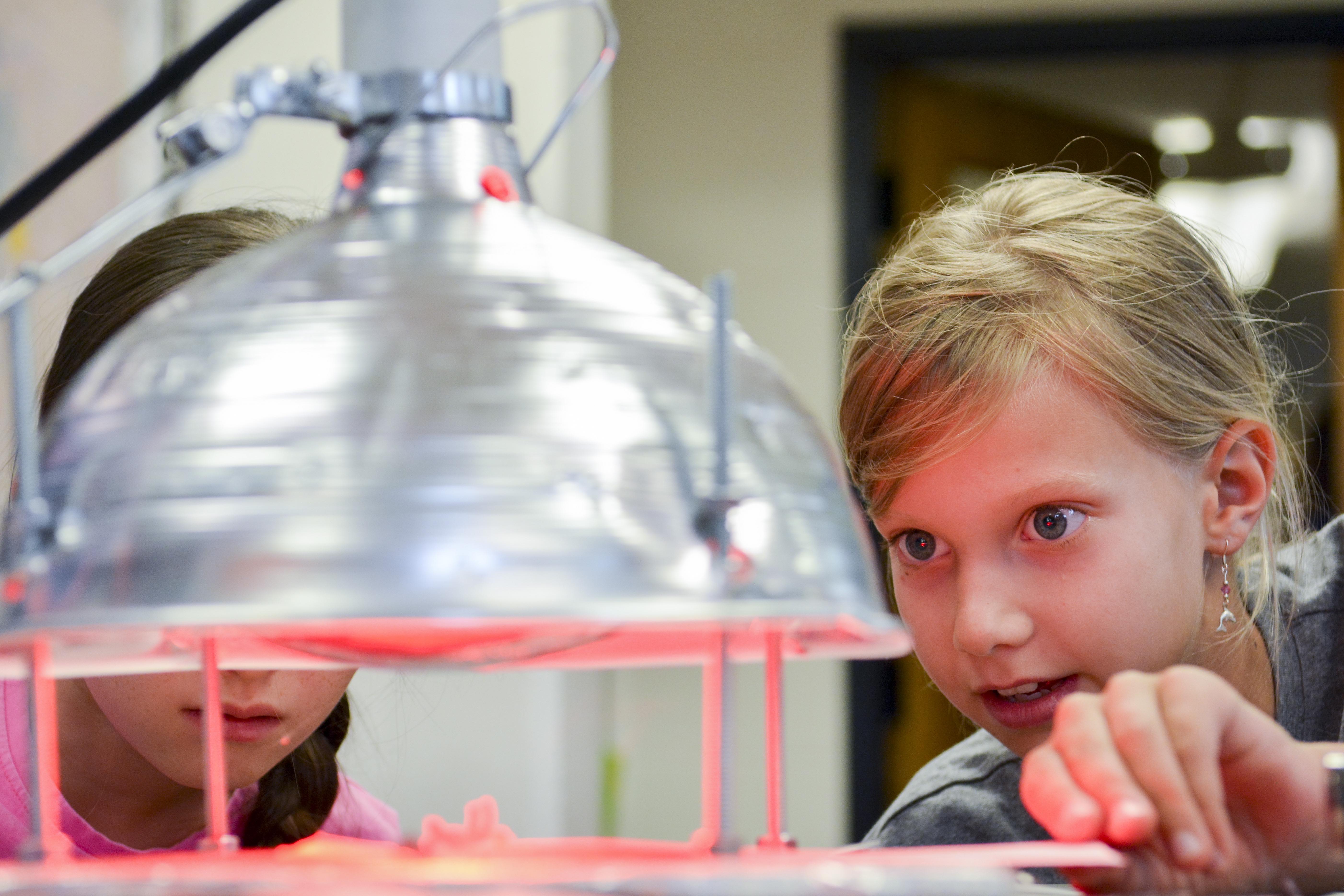

At the Science Learning Laboratory on the CU Boulder campus, 11-year-old Eliot Hwang admits if he were at home on this hot summer day, he’d play Pokémon. Or even study, he said, so he doesn’t get behind before school starts up this month. But here he is huddled around a heat lamp.

“It’s an excuse to get out,” the bespectacled Hwang laughed.

He and his friends are doing a version of innovative engineering research called “photo-origami” involving light-activated 3D structures. Hwang’s the kind of kid, when, you point at the giant periodic table on the wall and ask him what his favorite element is, he doesn’t skip a beat.

“I would say I like iron (Fe) because of its handiness for a bunch of stuff and ytterbium (Yb) just because it’s spelled funny and it’s so fun to say,” he said.

At camp recently, Hwang and his friends watched a bit of magic take place. They have tiny strips of “shape-memory” polymer – a.k.a. – Shrinky Dink. Teacher Eric Carpenter prepared the kids for what they’ll see once the polymer sheets go under the heat light.

“After about 30 seconds this polymer is going to start to wiggle, start to rise up, and start to shrink and lay back down,” said the energetic Carpenter. “It will literally go back to a shape that the polymer remembers.”

The kids get a big kick out of the transformation:

Carpenter is one of several instructors at CU Science Discovery, which offers a variety of hands-on STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) camps for kids ages five to 18.

Mimicking nano research

The kids' research is modeled after work being done at the nano scale at CU Boulder's College of Engineering and Applied Science in a million-dollar optics lab. Researchers there are developing new materials that are engineered to fold in certain places when exposed to light. It’s called Photo Origami. The light transforms a flat polymer sheet – that’s complex strings of molecules – into a mechanically robust, low-weight, high-strength 3-D structure.

Similar to what the kids are doing, this research involves creasing and folding. However in the high-level research, crease patterns are made through a chemical process that is caused by the absorption of UV light. The UV light initiates a reaction that locally causes the material to become stiffer and less soluble.

“Could I mail someone a flat piece of paper in the future?” asked CU Boulder research associate Beth Stade. “Could you shine light on it and it turns into a three-dimensional book?”

Researchers like to share what they’re learning with school-age students, but they knew bringing them into this tiny lab wasn’t realistic.

“But what we realized is we could do all the same bending, we could ask all the same questions with Shrinky Dink, which is a shape memory polymer that’s thermal activated," she said . "Instead of being activated by light, it’ s being activated by heat.”

For 9-year-old Molly Urbonas, it’s discovery that’s the fun part of camp.

“I’ve never been able to make other shapes besides what the package gave me but I’m very curious to find what the Shrinky Dink material is going to,” said Urbonas.

Imagining the future

There is no shortage of ideas when it comes to what these kids think photo origami can be used for in the future:

- “A portable robot that would shrink up and maybe move if you had the mechanics to do it. The military could deal with insurgents and mines."

- “It could be used for espionage. You could engineer things to help people carry a package the size of a mouse.”

- “It could be like a small package to rise up and become a cell tower.”

- “It could be used to make organs in the body.”

These students are asking questions and trying new things just like the graduate students, said research associate Stade.

“Our graduate students will say, ‘well what if we pre-stress it?’" said Stade. “I’ve heard students say, 'what if I pre-bend my Shrinky Dink?' The conversations are exactly the same. The materials are different. The labs are different. The scientific process is identical.”

Stacey Forsyth, director of CU Science Discovery, said there is a lot of evidence that if students don’t keep working on reading, science and math skills throughout the summer, those skills slip.

“We find really creative ways to get kids doing math and doing science in ways that are really fun so they don’t necessarily realize how much they’re learning,” she said. “It’s a real gem if we can use current science that’s happening now at the university as part of that effort.”

High schoolers in on the act, too

It’s not just the elementary school kids whose imaginations are being stoked – two high school kids help the younger kids out. They’re part of a six-week photo-origami research experience and mentorship program.

April Garland, 16, loved her math classes at Northglenn High School. She said helping with this camp broadened her view about what options there are for further study and career.

“In the first week we met chemists,” she said, “We met some people who are doing textile picture books for the blind -- I didn’t know that was a thing before! They’re so many new things out there instead of just math. You can have a subject within a subject.”

Nakai Barr, 18, said before the mentorship, he never thought about being an engineer.

“My entire life I was led to believe that only prodigies or very, very gifted children or individuals could do something like this," said Barr. "There’s room for everybody here. Anybody can be an engineer and I would really recommend that people look into it because that’s what the future is going to be."