Being poor in a ski town comes with its own set of frustrations.

For Crystal, who grew up near Steamboat Springs, it was hard to watch the snow bunnies arrive each winter to play in their expensive homes, while she raised two daughters on her own in a single-wide trailer.

The disparity made her wonder: How do some people have so much, when she just couldn’t seem to get ahead?

“I always thought I was going to be in poverty,” said Crystal on a quiet weekend morning this summer. She asked not to use her last name because she lives in a small town and poverty is a sensitive subject. “My kids and I have both been on Medicaid. We’ve been on WIC. We’ve been on food stamps. I don’t want to rely on that.”

Crystal sought out anti-poverty programs through the county human services department to improve her situation. What she found wasn’t the standard how-to-write-a-resume-and-make-a-budget training. Instead, she’s part of the inaugural class of an experimental Routt County program that aims to help people out of poverty by emphasizing quality of life as much as improving income.

This new effort is called Routt to Work and on a Thursday evening this past summer, the program’s first eight enrollees and their kids gathered in a Steamboat Springs church to share a meal and discuss how they were doing to meet individual goals.

Over cups of melting gelato, one participant confessed that extra hours at work had kept her from organizing her bills. Another proudly said she’d taken the time to prepare healthy, fresh food for her and her son, although the extra cost meant a few other things had gone unpaid. Crystal’s fiancé Anthony described taking one of his future step-daughters shooting, to help improve their family bond. And Crystal announced not only had she met her goal to apply for jobs, she’d actually landed one, a part-time customer service position at the local airport. The table erupted in cheers at her news.

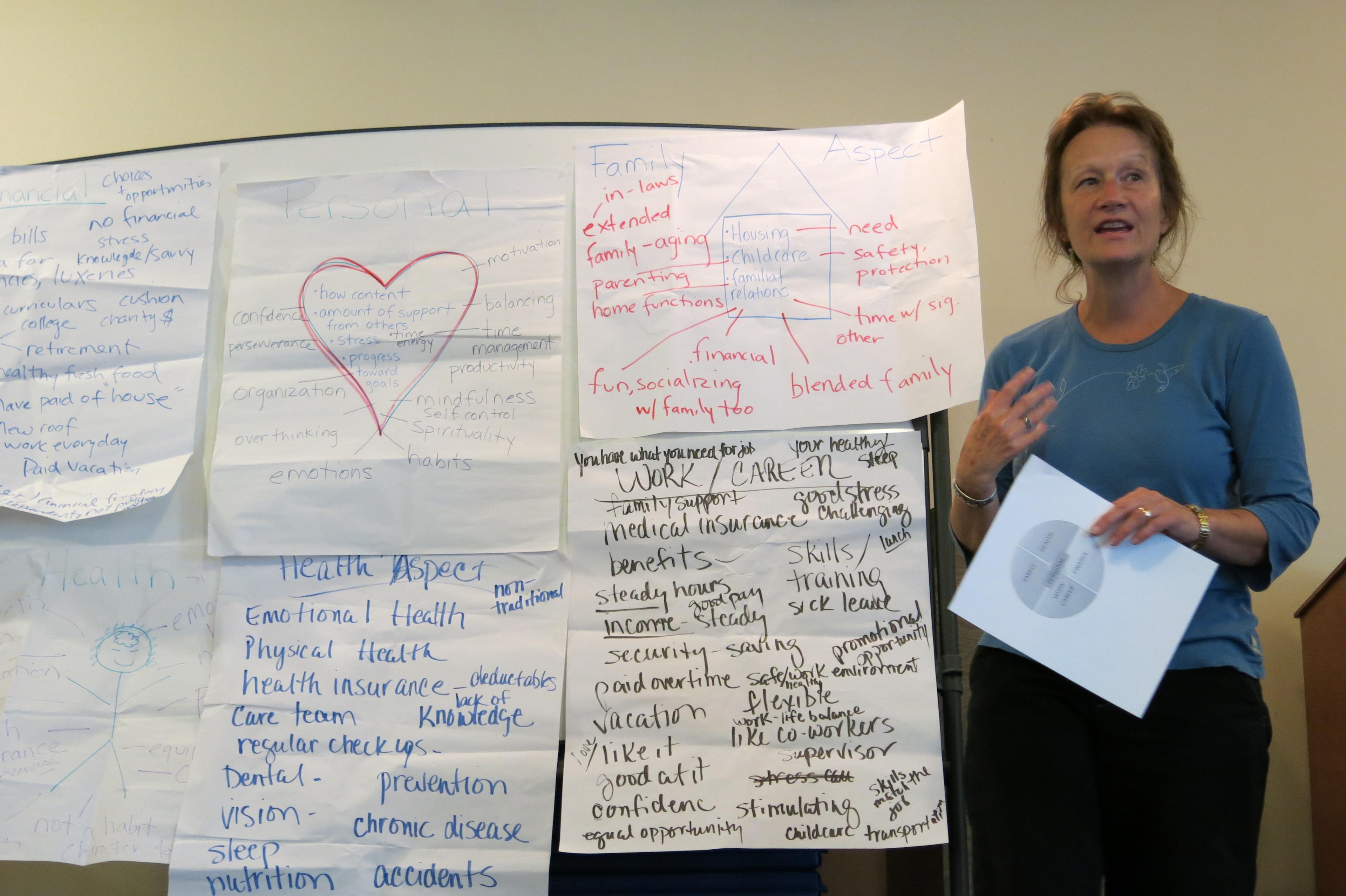

Routt to Work turns the familiar formula of social services on its head. Much of what government is geared to offer the poor are large, single-service direct assistance programs: food aid, job training, childcare subsidies. All come with strict eligibility requirements and narrow missions.

By contrast, participants in Routt to Work set their own goals, which may or may not be directly related to their economic situation. They’ll spend a year working with mentors to help them identify resources and navigate systems, while meeting frequently with the group for moral support and encouragement. Altogether the approach seems like a mix of anti-poverty life coaching and group therapy. For Crystal it appears to be working.

“What I've gotten from these classes is, ‘Okay, slow down enough to know what I want. Now here's how to go get it,’” she said.

A ‘Radical Notion’ Born Of Frustration

Routt to Work is the homegrown creation of the county’s human services department, in partnership with a couple of local nonprofits. But Routt isn’t the only place in the state experimenting with this small-group, intensive-mentoring approach to help people out of poverty.

In Jefferson County, Human Services workers started talking with Head Start families about what the parents thought would improve their situations. The result of those conversations is the JeffCo Prosperity Project, which is now in its fourth year.

“It’s kind of a radical notion, right, what if you listened to families?” said Joyce Johnson, JPP’s director. “What if you said, ‘What do you need?’ and then helped them find that?”

That philosophy has lead Johnson places she never expected as a career social worker, like into meetings with local auto mechanics to pitch them on donating their services. But as a result, JPP families can now get help before a flat tire or a dead battery has a chance to spiral into a lost job.

Jessica Valand, who oversees job training programs through Colorado’s Department of Human Services, says programs like JPP and Routt to Work are signs of a shift in thinking about what it takes to help the poor. She sees social services professionals who are increasingly disillusioned about the power of traditional safety net programs to help people meaningfully improve their lives.

“It’s so frustrating to have somebody come in the door [at human services] and you’re only able to help them for a little bit … and then they’re back six months later,” Valand said. “I think there is just this sense of, ‘Dammit, we have got to be able to do something about this.’ It just feels futile.”

One reason that efforts like Routt to Work look promising to Valand is that unlike more focused direct-assistance programs, these experiments try to support members across many aspects of their lives, proving “wrap-around” services to meet multiple needs at once.

That approach starts by acknowledging that what holds someone back from improving their economic circumstances might not be a lack of experience or education, but uncertain childcare or untreated health issues, and then having the resources to address those issues.

Designing a program that takes the broad view isn’t easy, though.

“It is very nuanced and complex to try to think about and engage people in that whole-person mentality,” Valand said. “We’ve got a long way to go in that respect.”

Does It Work?

New as these programs are, there’s a lot of interest in figuring out whether they’re working. After all, the history of anti-poverty interventions is littered with efforts that looked great on paper, but failed to deliver in the field.

“It’s all a bit of an experiment,” JPP’s Johnson said. “But I don’t want to give the impression that it’s completely removed from any research … It’s a little bit of both.”

JPP recently got a grant from the Daniels Foundation to try to measure its impact. But Johnson says it’s tough to measure how different families’ progress in the program, when they’re starting from very different situations and trying to reach self-defined goals.

“Stay tuned,” said Johnson.

There is one ‘wrap-around’ effort in the state that has been around long enough to have some data on participant outcomes. Boulder County is one of several communities that has implemented a national program called Circles. So far three groups of ‘Circles Leaders’ have completed the 18 month program.

According to data from the national Circles programs, participants self-report that their income increases an average of 88 percent over the course of the program – in large part because many are unemployed when they join Circles and then find work – while their reliance on public assistance drops by nearly a third.

While those numbers are impressive, these types of programs face a big hurdle: they’re small, especially when compared to the number of people living in poverty.

Circles has fewer than two dozen people at a time going through the program. The JeffCo Prosperity Project covers 35 families. And Routt to Work started with 11 members and is now down to seven.

“I can’t imagine doing it any bigger than that,” said Routt County Human Services Director Vickie Clarke, about Routt to Work. “It’s intense.”

Routt to Work has two part-time staff and runs on an annual budget of around $60,000. If it manages to help seven people get – and stay – out of poverty, Clarke believes that’s money well spent.

“A good place to invest our time, energy, resources is where you might have the best chance for an impact,” said Clarke.

Size isn’t the only reason this approach is unlikely to ever become a panacea for poverty. These programs aren’t just limited in how many people they can serve, but the type of people.

“We need folks to have a certain amount of stability in their lives to even be able to do the work that we’re asking them to do,” said Jessica Austin, head of Boulder Circles. “If you’re dealing with a domestic violence relationship, or you’re currently homeless and you’re looking for housing, you simply don’t have the bandwidth to do the kind of introspection that Circles is asking you to do.”

Program participants themselves say that stability is just one prerequisite; you also need drive. Or as recent Circles’ participant Tracey Jones puts it: “You have to be in a place where you’re sick and tired of being sick and tired and you’re ready to move.”

Finding Success

During her time in Circles, Jones wrapped up a messy bankruptcy and started working full time as certified nursing assistant. Life hasn’t been easy since she completed the program a year and a half ago, and Jones says there are definitely days when she wants to give up. But the skills she's learned and the support she still gets from friends in Circles make a huge difference.

“Now I’m moving to the next level,” said Jones. “I’m still flirting with poverty, very heavily. But I can see the light at the end of the tunnel now.”

Jones’ rental house in Longmont is a testament to how much she values Circles. She's hung a dream board by her front door that she made in the program. It has pictures of the home she someday hopes to own and vacations she'd love to take. Across from it, her Circles completion certificate stands out on an otherwise empty wall.

“I actually don’t have any degrees up there. Those are sitting in the closet,

Jones said, “But, yeah, that is a very hard-earned piece of paper. I put it up there to continue to motivate me.”

Jones is still working to reach the middle class comfort she aspires to. But for supporters of programs like Circles, her progress so far is more proof that the future of anti-poverty efforts should be smaller, more nimble, and led by the poor themselves.

This story is part of our ongoing exploration of Colorado kids who are living in poverty, how it affects their lives and our common future. We'd like to hear your ideas about what can be done about child poverty in Colorado. Share your thoughts through our Public Insight Network or comment below.