NIH. That would represent a 20 percent drop in funding for biomedical research.

“We were shocked.” said Dr. Kathleen Barnes, who leads the Colorado Center for Personalized Medicine at University of Colorado Anschutz medical campus. “In my almost 25 years of NIH-funded research in academic medicine, we've never experienced a threat this great to the NIH.”

CU’s School of Medicine, where Barnes works, gets about $200 million a year in NIH funding, so a 20 percent drop could make $40 million vanish. Barnes points out that there’s “no historical precedent for a drop that drastic in the NIH budget.”

Personalized medicine, which is Barnes’ specialty, is one of the many kinds of research the NIH funds. The story of a patient named Namourou Konate helps spotlight how research can make a difference.

Last November, Konate had a big scare when he lost his vision and ability to speak. His wife rushed him from his Aurora home to the emergency room. Konate, who’s originally from West Africa and for whom English is a second language, said that he couldn’t even talk.

“They ask me my name and I can't even remember!”

He was having a mini-stroke, a condition brought on by high blood pressure. His ER arrival coincided with an NIH funded study looking at high blood pressure. Konate allowed researchers to map his genotype. That lead his doctors to switch medications, which has made a big difference.

“Everything is normal,” Konate said. “So it's a good thing.”

Dr. Andrew Monte, one of Barnes’ fellow researchers, said they learned Konate’s cells have high levels of an enzyme that responds to one drug much better than another. He suggests that this information made a difference in his life because they are “able to actually treat his blood pressure more effectively knowing his genotype.”

Researchers are able to identify new genes by mapping the genome of large populations, in this case that of people with African ancestry. Which brings us back to the research of Dr. Kathleen Barnes.

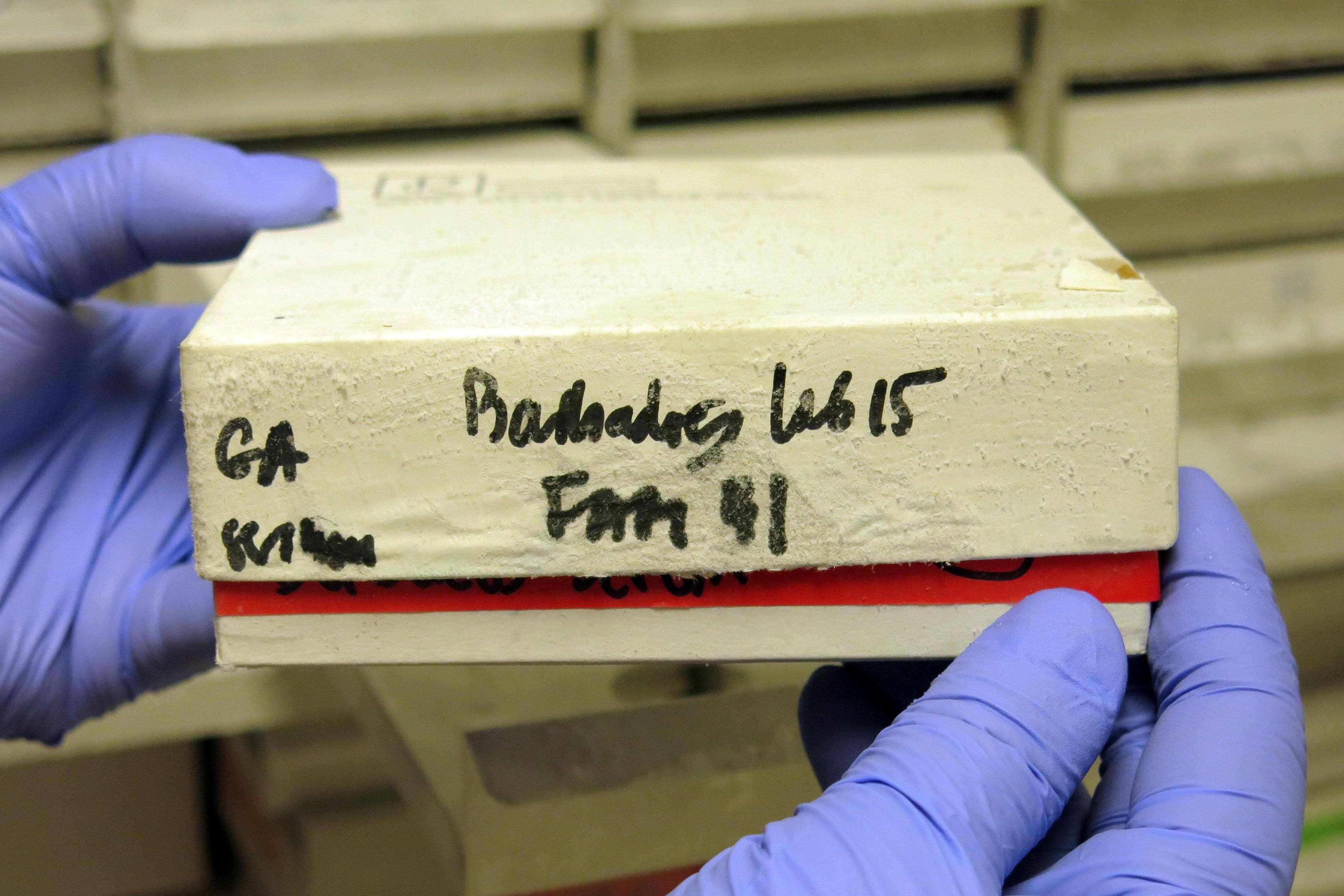

Inside a large freezer in her lab are trays of tissue samples from around the world. Studying the samples they’ve created a massive genetic catalog — including the largest ever sequencing of people with African ancestry in the Americas. Barnes said researchers identified changes in their DNA that puts them at higher risk for certain diseases.

“We miss a lot if we're only studying Europeans,” Barnes said. “Because at the end of the day we're all Africans, modern humans moved out of Africa.”

People of African ancestry in the Americas suffer disproportionately from chronic illnesses like asthma, diabetes and cardiovascular disease, but the reason has remained elusive. This research will add to a public database. Given that, it will also let doctors better track, predict and treat diseases. Barnes said “it has the potential to save a lot of lives.”

It’s also the kind of work and research that does not come cheap.

A $10 million NIH grant funds the project and pays for, at least in part, about 70 jobs. Barnes is waiting to hear about a renewal of the programs NIH funding. She worries deep cuts to NIH’s budget will severely hamper cutting edge research in biomedicine, a field in which the U.S. currently leads the world. It’s also just the start of the long federal budget process, so it’s unclear what, if any cuts, the National Institutes of Health would endure.

“It does have huge potential implications for research in general and would really be a pity to cut it at this point,” Barnes said.