Stephen Szutenbach didn’t have anywhere to turn when his priest and mentor came on to him sexually when he was 18 years old.

Szutenbach aspired to be a priest himself. He had never even kissed anyone before.

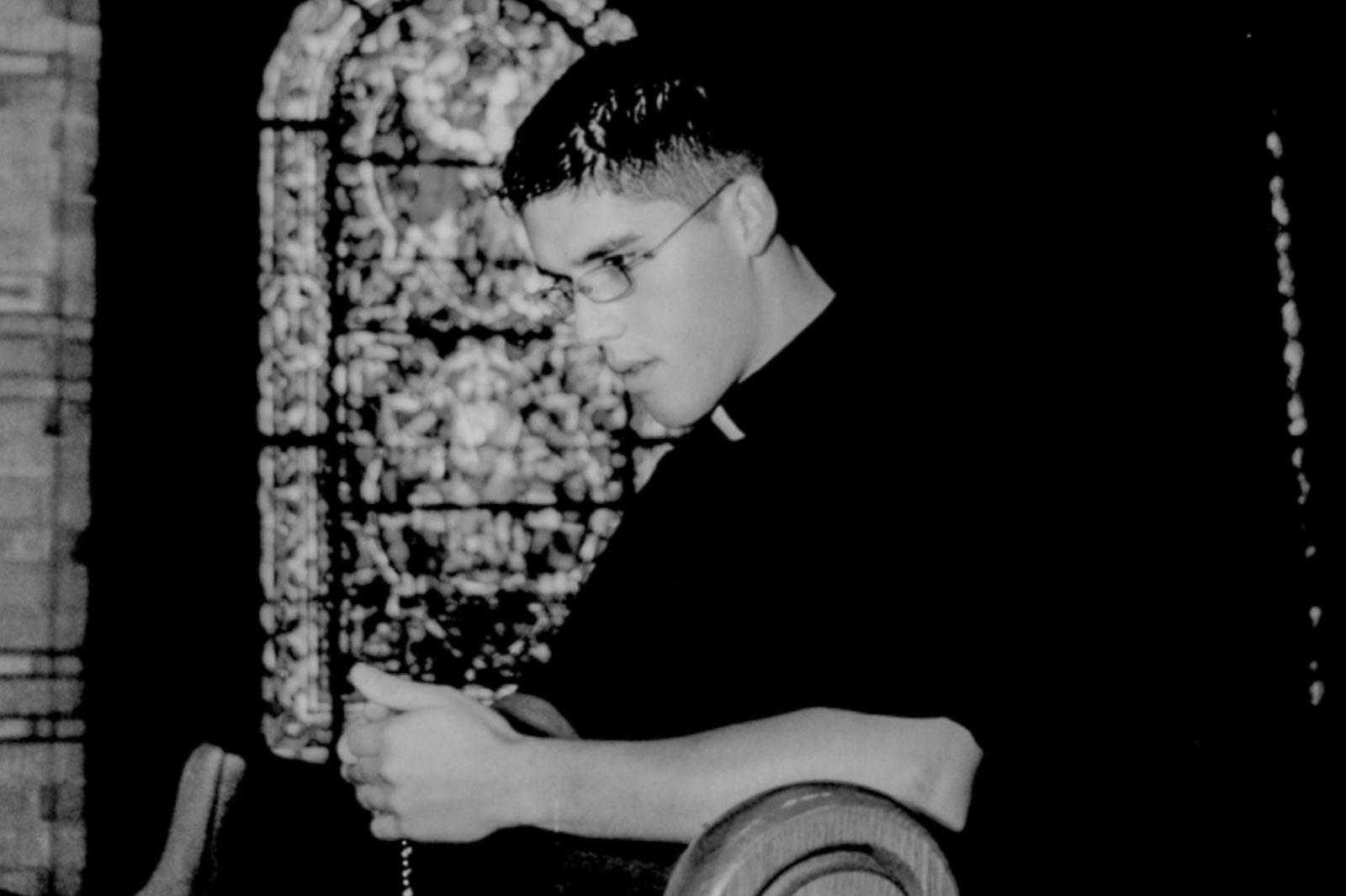

He first met Rev. Kent Drotar, a leader at St. John Vianney Theological Seminary, at a youth retreat in 1999. It was the summer before he started his senior year at Conifer High School.

Szutenbach was having trouble with his parents and confided in Drotar. The priest gave him advice and counsel and supported him personally and spiritually throughout his last year in high school. He attended his swim meets and graduation, where Szutenbach delivered the valedictorian speech in 2000. Drotar gave Szutenbach a laptop computer after graduation.

“I saw him as a friend and a mentor,” Szutenbach said. “And as a father figure.”

That summer, Szutenbach was slated to start seminary and got a job working on the grounds at Denver’s St. John Vianney Seminary. Drotar often had him over for lunch in his apartment.

“Slowly but surely as the summer went on, we would be sitting on the couch eating lunch, he would put his arm around me, he would put his hand on my leg and try to cuddle with me,” Szutenbach said. “It made me uncomfortable.”

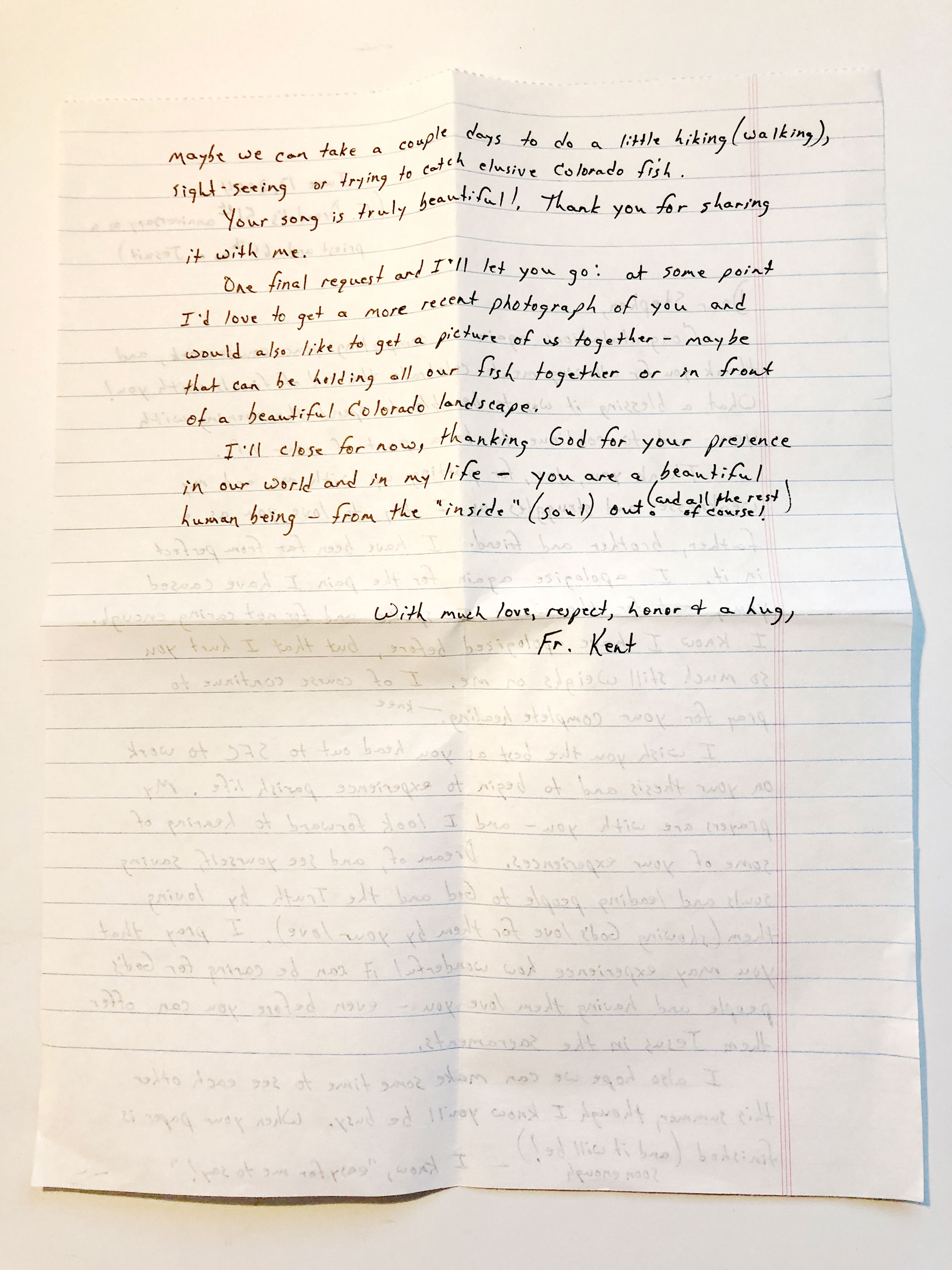

The two went on a fishing trip to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison and got a hotel room with two beds. Szutenbach awoke to Drotar in his bed, fondling him. Szutenbach reminded him of the vows he took to become a priest. On the long drive home, Szutenbach said he felt tortured.

“I just remember feeling just incredibly icky throughout the whole thing,” Szutenbach said. “He offered to hear my confession, which is against canon law, because you can’t absolve someone for a sin for which you are party to.”

Szutenbach said Drotar continued to pursue him for several more years as he worked through seminary.

In 2004, four years into his work and education to become a priest, Szutenbach decided to leave Colorado because, he said, he wanted to get away. He also wanted to start living his life openly as a gay man. When Szutenbach told Drotar he was gay, Drotar told him God didn’t make gay people.

Drotar did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Colorado Public Radio.

Szutenbach went on to graduate school in Florida. He still lives there with his husband. He designs hospitals for a living. He never told anyone what happened until 2007, when he was back in Denver over the holidays to visit one of his favorite former professors, Marica Frank.

She told him one of his former classmates was having trouble getting ordained because Rev. Drotar said he acted “too flamboyant.” Szutenbach told Frank that was ironic given what he had been through with the priest. Frank stopped him.

“He told me enough that I could tell that this was a case of sexual abuse. And so I named it. I said, ‘Stephen, you realize you were sexually abused,’” Frank said. “And that didn’t seem to have occurred to him … He hadn’t framed it that way.”

Frank told her colleague Jeanie Engelbert, who at the time taught classes at Vianney and was on the pastoral formation team. Engelbert went straight to Friar Michael Glenn, St. John Vianney’s rector, and told him the whole story.

“I had complete faith that they would honor the young man and do the right thing,” Engelbert said.

Within a couple of weeks, Drotar was sent away for a couple of months of therapy. Engelbert and Frank figured that was the end of it and he wouldn’t get another assignment. But when Drotar returned later that spring, Engelbert read in the Catholic Register that he was assigned to a parish — with a school.

“My thought was whoever, wherever they sent him, whoever treated him, obviously didn’t get it,” Engelbert said. “So, I needed to let them know. I was speaking from my clinical understanding, my psychological training, my theological training, he must not get it. So I’m going to lay it out very clearly.”

She confronted then-Archbishop Charles Chaput about the assignment and he said he had documentation from the therapist, who treated Drotar, that he was fit to serve in a parish.

Szutenbach was also dismayed at the assignment and asked for a meeting with the head of the Archdiocese of Denver.

“I said, in no uncertain terms, ‘either you do the right thing or I’m going to go to the press,’” Szutenbach said.

After that meeting, Chaput created a conduct response team, which removed Drotar from the parish within a couple of weeks. The archdiocese eventually stripped Drotar of his rights to call himself a priest or act as a priest anywhere in the world.

Archdiocese spokesman Mark Haas said the archdiocese handled everything correctly.

“The information available to them at each step, they followed each step and the ultimate outcome was this man was removed from the priesthood,” he said.

Haas said Chaput learned additional details at the August meeting with Szutenbach — and that sparked him to convene the review team to look into the allegations. Szutenbach said the only thing new at the meeting with Chaput were the threats to go to the media.

“The reaction of Archbishop Charles to protect himself and his reputation and the seminary’s reputation is a complete act of clericalism,” Szutenbach said. “It’s more important than the truth or honesty or transparency or good faith.”

Szutenbach is speaking up about this now because of recent revelations about seminarian abuse across the country. Szutenbach first told his story to the Philadelphia Inquirer, which is working with the Boston Globe on a series of stories about failures in the Catholic Church to address systemic abuse. Chaput is now the archbishop of Philadelphia.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops met last week to address the Catholic abuse crisis and left without adopting any reforms.

Szutenbach told Colorado Public Radio he is disappointed in how Denver’s archdiocese handled his allegations of abuse — and he has been waiting for more than a decade for leaders to laicize or defrock Drotar.

Szutenbach said he was told, again, in October that the archdiocese is working on it.

It’s important to Szutenbach because he had found references on social media where Drotar still calls himself a priest as recently as 2017. He worries Drotar could serve again somewhere under a different archbishop.

“I really hope they do what they said they were going to do 10 years ago,” he said. “He hasn’t been active as a priest for 11 years. You know, laicize him.”

Diocese spokesman Haas said he wouldn’t go into communications the archdiocese has had with Szutenbach. He noted that defrocking a priest takes permission from Rome, and Drotar is, for all intents and purposes, not able to serve as a priest in any capacity.

“We are not trying to minimize at all the experience this young man went through, but we do want to stress that from what we can do the archdiocese handled this just as it should have,” Haas said. “He’s not acting as a priest anymore. The process worked. He is no longer in ministry in Denver, in Colorado, in the U.S.”

Szutenbach said his Catholic faith actually survived the abuse and he still practiced after he left seminary. But it hasn’t survived the way he has been treated since he came forward.

“If you truly believe the church is a sacred institution, you’re doing something that is sacred holy, even if you’re doing something that is objectively wrong and disordered and evil,” Szutenbach said. “They’re so afraid of looking weak or unholy. They’re terrified of looking like they’re doing something wrong. That’s why there are so few apologies.”