It's a group no one wants to be a part of: communities scarred by abuse in Catholic Churches.

With the Attorney General's office's report, Colorado now has at least a partial accounting of child sexual abuse in the state’s three dioceses. The independent inquiry revealed that priests abused, at minimum, 166 children in Colorado over 70 years.

The Centennial State is far from the first community that has already been down this path.

A prominent one is Boston, where in 2002, the Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigation revealed widespread sexual abuse of children by priests in the Archdiocese of Boston and an ensuing cover-up by church leaders.

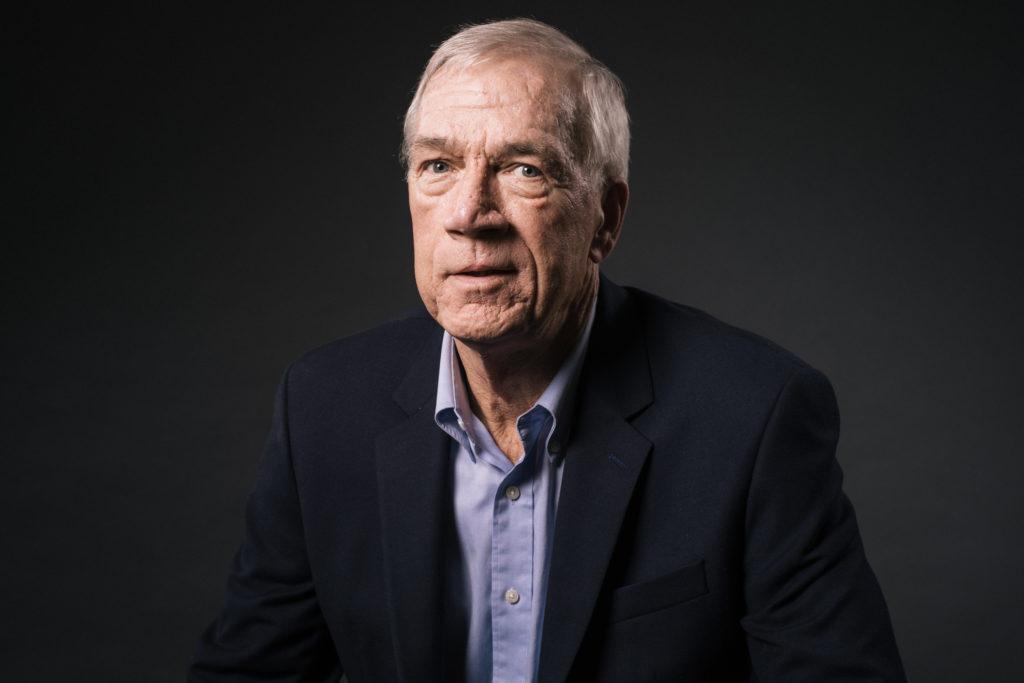

Walter Robinson led that coverage as the Spotlight team’s editor. The stories drew national attention and won the paper a Pulitzer. The 2015 movie about the reporting, “Spotlight,” won Oscars for Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay.

When Robinson spoke to Colorado Matters, he said Colorado’s special report was “eerily similar” to inquiries in Massachusetts and other states.

Interview Highlights

On the Colorado special report's finding that "over 50% of Colorado’s clergy child sex abuse victims were abused after the relevant diocese was already aware these priests were abusers":

"The church decided that the reputation of the church and of the priest, was more important than the welfare of the children. And time and again, the church here, and in Boston and everywhere else, they moved priests around. They persuaded parents, when parents found out, not to say anything, they gave priest second chances. They treated these crimes as sins to be forgiven, and not something that needed lifelong treatment."

On the limitations of the inquiry, which was reached in an agreement with the Catholic dioceses and the Attorney General's office:

"The attorney general's office in the report made it very clear that they, essentially, did not have the ability to give a full accounting. I think you described it as a partial accounting, and that's correct. Many of the files were incomplete, barriers to reporting still exist. There were significant errors in much of the reporting. Critically, the dioceses, they made the decision which files of dead or retired priests to turnover.

I should add here, you mentioned the partial accounting, and the report is very clear that the investigators didn't get everything they wanted. In states where a grand jury has sat and subpoenaed all the records, the number and the percentage of priests who abused children is generally a good bit higher than in states where there was a voluntary agreement reached with the church."

On why it has taken Colorado and other states more than 15 years since Massachusetts’ attorney general launched an inquiry into clergy child sex abuse to make inquiries of their own:

"It's not too complicated. In most jurisdictions, in most states, the authorities were reluctant, and sometimes frightened, to essentially take the church on by impaneling a grand jury and demanding the records.

I mean, even in Boston in 2002, the attorney invited the Cardinal and the bishops to testify before the grand jury and they refused, and he had to subpoena them to get them in. And it took an enormous amount of courage back then for an Irish Catholic attorney general in Massachusetts to take that step. And in the intervening years, not much has changed around the country, until the attorney general in Pennsylvania decided to do a grand jury. And when he did it, and it revealed that in six dioceses there were 300 priests who abused children, and he was widely applauded for taking that step. All of a sudden, around the country, prosecutors and attorneys general realized that there was no political downside to taking this on.

And so we now have over 20 states where prosecutors, in one way or another, are involved in this."

On the financial impact these reports can have on dioceses:

"Well, in many cases, and Boston came close to this, there have been bankruptcy filings by the dioceses or the archdioceses. I think about 15 dioceses around the country have gone into bankruptcy because of the enormous costs of these settlements. In most states where there have been movements to change the law to allow victims to seek civil redress all these years later, the church has fought this legislation, in some cases successfully.

So one issue here in Colorado, and I'm not that familiar with the statute, but if the legislature were to open up a window for all victims to come forward, the number of victims, and surely the number of priests accused, would probably go up dramatically. "

On why the Catholic Church has a long way to go before putting this behind it:

"Even in the U.S. Catholic Church, where there has been much greater disclosure and certainly much more comprehensive reforms, there are many dioceses where there hasn't yet been an accounting, or even a full accounting. And certainly, elsewhere in the world, there are many countries where there's been no acknowledgement, or virtually no acknowledgement that the problem existed at all. When, in fact, it was as bad as anywhere that we know of in the U.S."