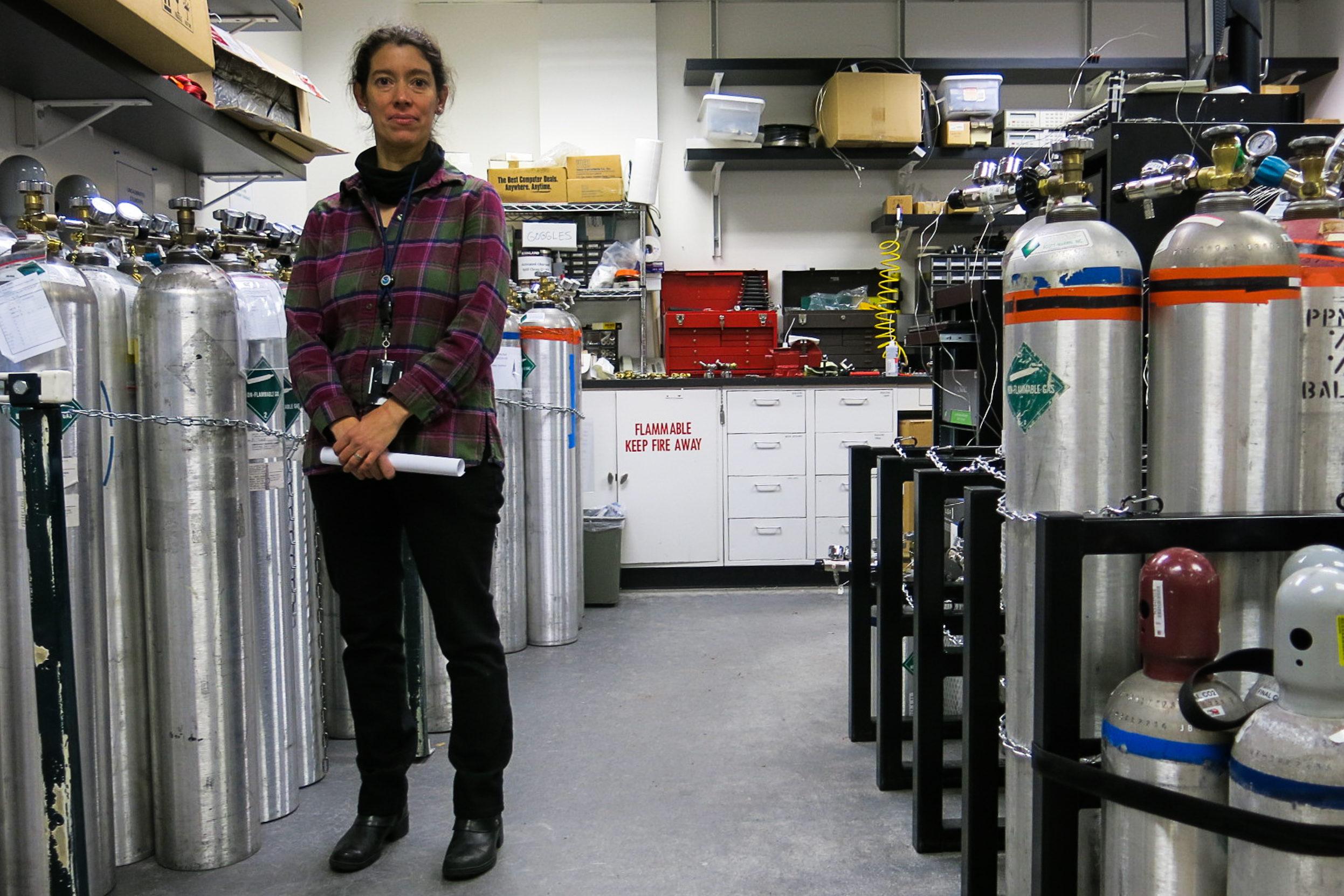

Scientist Gabrielle Petron looks out into the world and sees numbers. In her work for the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, Petron plots data on her computer like most people complete a shopping list on the back of an envelope.

This fall, her love of data motivated her to go to the Colorado Department of Health and Environment’s website. At night, with her daughter doing homework in the background, she graphed Colorado’s methane levels in 2017 and 2018. Something didn’t seem right; dozens of data points recorded methane levels lower than those measured at the South Pole, home of the planet’s purest air. So she plotted them again. She double-checked them and went over her work.

Finally, she had to conclude: Much of the data recorded at the state’s two methane collection sites in Denver and Platteville between mid-2017 and mid-2018 seemed wrong.

“I was kind of shocked,” she remembers.

Petron was right.

State regulators at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment acknowledged to Colorado Public Radio that several of the publicly available data files on the presence of methane in Colorado’s air were inaccurate. After questions from CPR, the state uploaded data files with “reprocessed” methane numbers to address issues that originated from a third-party lab. They say the incorrect data don’t affect their ability to track methane emissions.

Researcher Petron still has questions about the corrected state methane numbers.

Accurate numbers on methane levels matter because the state of Colorado has adopted aggressive climate goals designed to reduce the amount of heat-trapping gases like methane. Lawmakers like Democratic State Sen. Steve Fenberg say the state needs an accurate report of where it’s starting from in order to know if it’s making progress.

“The state government doesn’t have the data that everybody has confidence in to make sure we know how to set ambitious goals and how to meet them,” Fenberg said.

Colorado Spikes The Ball On Methane Reduction

Methane is a scentless, invisible gas that can have 86 times more global warming potential compared to carbon dioxide over two decades. The greenhouse gas dissolves into carbon dioxide in about 12 years. Methane’s potency has made it a target of policymakers seeking a quick way to curb the effects of climate change.

In 2014, Colorado became the first in the country to crack down on methane, which can escape from oil and gas wells, lines, equipment and tanks, as well as from landfills, cattle operations and natural seeps. The state required oil companies like Noble and Anadarko to regularly inspect and repair leaks at their biggest facilities. Then-Gov. John Hickenlooper stood on stage with oil executives and groups like the Environmental Defense Fund to celebrate the news.

In 2016, the Obama administration even followed Colorado’s lead and announced a federal methane rule, now threatened with rollback under President Donald Trump.

In 2019, Colorado’s Democratic lawmakers went even further when they passed sweeping new regulations for the oil and gas industry. Included in the new law was a section that sought to further crackdown on methane emissions and the accompanying volatile organic compounds that can escape from wells.

“We are the model nationwide along with California and a [few] other states on how to most tightly regulate methane,” said John Putnam, head of environmental programs at the Colorado Department of Health and Environment. “All eyes are on us right now for the rulemaking that we have, and the rulemakings to come, because states know that will set the standard.”

In the contentious world of environmental policy, oil trade groups, environmental groups and the state of Colorado have declared the state’s methane rule a success. They point to company-reported repairs that have addressed thousands of methane leaks.

But Petron’s digging, confirmed by CPR, found that the state’s air methane monitoring system is ill-equipped to verify that success story.

As a scientist at CIRES, Petron was among the first to measure methane at hot spots in Weld County, the epicenter of the state’s energy boom. In 2008, she spent weekends taking her daughter, who was an infant at the time, along in her car to scope out oil and gas sites, where she would measure spikes in methane and VOCs. Today, her 12-year-old daughter is a companion in her data obsession. Even their everyday interactions pivot on percentages: “Are you feeling 50 percent or 80 percent better compared to yesterday?”

So, she knows exactly what methane levels ought to look like for Platteville and for Denver. After mapping the state’s data in 2019, she took her graphs into work at CIRES, which is affiliated with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Boulder. She compared state methane measurements to those her agency regularly takes at the South Pole.

Here’s what she saw: At the South Pole, methane levels annually hover around about 1800 parts per billion. In Platteville, deep in the heart of Colorado’s oil and gas country, methane samples measured as low as 1090 parts per billion.

“Then it became clear, it sounded familiar,” recalls Petron. “We had once again data for methane measurements that were much lower than the cleanest place on Earth. And that was not realistic.”

It wasn’t the first time she had encountered similar errors in Colorado’s methane data set. Back in 2014, after a journalist asked her questions about why Colorado state data were lower than South Pole numbers, Petron raised the issue with the state agency in charge of tracking methane. She provided air canisters with known methane levels in an effort to point state officials in the right direction to adjust their methane values.

“I think there’s been good collaborations in the past. We’ve tried to be responsive to when she’s brought up issues to us,” said Gordon Pierce, technical services program manager at the state’s Air Pollution Control Division, which is in charge of data collection.

When Bureaucracy And Data Collide

For the past five years, state officials have touted lower methane levels thanks to rules that require energy companies to seek out and repair leaks at well pads. The data questioned by Petron support this conclusion.

“Yes, average emissions per well site have probably dropped,” said Detlev Helmig, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder who regularly sets up field sites to measure methane and other compounds. “But that does not mean that total emissions for the region have decreased.”

That conclusion is supported by a recent research paper, which says methane and ethane emissions associated with Colorado oil fields have remained constant. The date range researchers examined was 2008 to 2015; state regulations kicked in in 2014.

The state has proposed even stricter limits on methane and volatile organic compound emissions, as well as ambitious goals for cutting the state’s carbon footprint. A formal hearing for the new oil industry rule on methane is slated for mid-December.

CPR contacted the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment about issues identified by Petron. While a CPR review of correspondence revealed state officials identified methane data problems in June 2018 and fixed them in August 2018, the agency took until October 2019 to update the state’s public data files.

“You do the best that you can, you make the changes as you see issues come up,” Pierce said.

While the state has had issues with methane data in the past, Pierce said there are other data points that show oil and gas emissions are going down. When an oil well leaks methane, it also leaks propane and ethane. Those volatile organic compounds are measured from the same air canisters by the third-party lab Atmospheric Analysis and Consulting.

The state’s vendor declined to speak to CPR. But CPR did obtain emails sent between the state and Atmospheric Analysis and Consulting via a Colorado Open Records Act request.

The emails show that the state started asking questions about potentially inaccurate methane levels soon after AAC took charge of processing state data in early 2017. State officials continued to ask questions about methane data through 2017 until late summer 2018.

“There are times in methane where there have been issues,” Pierce acknowledges. “We feel that currently what we’re getting is reasonable. That’s what we have to go with.”

Sen. Fenberg, who oversaw the state’s ambitious new legislative goals for carbon cuts, said he’s aware of the data issues. He’s had conversations with scientists concerned about the quality of the state’s methane data and volatile organic compound data.

“I’ve been hearing from some scientists that they feel like the trends are going in one direction, and the state government is saying that they’re going in the opposite direction,” Fenberg said.

The state process collects air for three hours in canisters at sites in Denver and Platteville early in the morning. Those flasks are collected every six days. They’re then sent via FedEx to the third-party lab in California to process. Each month, the state gets a data file of results. Those results are posted annually to the state’s air quality data collection repository.

In 2014, when Petron first identified issues in Colorado’s methane data, the state contracted with a different company, Eastern Research Group, to analyze samples. Pierce said those issues were eventually resolved and the data corrected. It uploaded new files to the repository. But in mid-2016 when the state of Colorado switched to Atmospheric Analysis and Consulting, new problems cropped up with methane data.

“We did not necessarily want to switch labs, but per state rules, we had to go out and re-bid,” said Pierce.

According to a 2016 bid sheet obtained by an open records request, AAC underbid the state’s old lab by about $30,000.

All told, the state spends about $84,000 annually to send air canisters to the California company every six days for measurement. Per state instructions, the lab tests the air for 74 different compounds, many of them the airborne pollutants that the state says it relies on in lieu of methane to track lower emissions from the oil and gas field in Weld County.

Are Lower Methane Counts Really The Goal?

From the state’s perspective, the numbers on methane levels that worried Petron were nearly irrelevant.

“Really [methane data] feeds into nothing,” Pierce said. He and the agency say they use other measures for policymaking and enforcement. “We use it for information purposes but that’s about it.”

Right now, the state of Colorado has several tools that track progress on methane: the dataset Petron questioned, a greenhouse gas inventory that estimates methane emissions and annual leak detection and repair reports submitted by oil and gas companies. Those energy companies could be required to estimate their overall methane emissions in 2020 if a proposed rule is approved by the Air Quality Control Commission in December.

The state’s other sources for tracking methane emissions have their own issues and limitations.

Colorado’s greenhouse gas inventory tool — one of three the state uses to estimate methane emissions could be undercounting emissions.

“We’ve done several atmospheric studies at the regional scale that show the [state] inventory either for methane or for VOCs were too low compared to what the atmosphere was telling us,” Petron said.

She has noted lower oil and gas emissions estimates by Colorado state officials in other research projects she’s published.

Fenberg said as climate and air quality goals become more important, he wants to see an additional level of scientific scrutiny.

“We absolutely need to do better. We know air quality is more of a problem,” the Democratic legislator said. “We know that the data is sometimes confusing and is actually telling us something opposite from what we are experiencing on the ground. We need to look more into that. And I think that probably means spending more money and resources into monitoring and data analysis.”

The state’s methane tracking efforts are limited in part because federal regulations don’t demand much in the way of cutting methane emissions. In spite of the state’s growing emphasis on cutting planet-warming emissions, Pierce said the agency’s main focus is still on federal regulation, which focuses on ground-level ozone, not methane. Colorado has been out of compliance with federal Environmental Protection Agency standards for ozone for years.

State officials like Pierce do still care about methane. As Colorado oil companies ramp up production to record levels, that can mean higher VOCs and methane. If the state can lower those emissions, that could mean less ground-level ozone production. So it’s in the state’s interest to keep a watchful eye on, even as it doesn’t prioritize tracking methane closely across Colorado.

The state also faces significant technological hurdles. CDPHE’s Pierce said methane has been a tricky substance to monitor because third-party labs use a different analytical technique to measure it compared to what’s used to measure VOCs.

“I doubt whether any other [states] are testing much for methane,” Pierce said.

‘Beautiful’ Methane Data Does Exist

Other institutions in the state have far more rigorous methane measurements for several years. That includes the source monitoring done by Petron, aerial surveys by NOAA and private companies like Scientific Aviation, and Helmig, the CU professor, who has done real-time monitoring.

“We have the only place in the state that measures VOCs in real time,” Helmig said. “It’s a complex measurement. It takes experience to build instruments and run it.”

Monitors in Boulder test VOCs and methane every two hours. The information is stored along with wind data and uploaded to the county’s website.

In 2019, after more than two years of data collection, Helmig said the patterns are clear. When the wind blows from the northeast carrying Weld County air onto Boulder Reservoir, both methane and VOCs increase.

“We clearly see differences in air composition and pollution levels depending on wind patterns,” he said. “It’s the most beautiful data set I’ve generated in my 30 years of doing atmospheric observations because it’s so clear and obvious.”

In terms of quality control, Helmig tests his equipment weekly using calibration standards set by NOAA and the World Meteorological Organization.

“We love audits,” Helmig said. “Anyone who wants to audit us, please come here. The more audits the better.”

The biggest difference between the Boulder system and the state system is cost. CU Boulder’s system operates in real-time and they’ll spend $120,000 in 2019 to operate. The state reports numbers annually and will spend $84,000 to analyze canister data and upload their spreadsheet once a year. Still, when Helmig and the University of Colorado bid on the state contract to track methane in 2016, they were underbid by just $3,990.

Right now the state of Colorado does not use Boulder’s air quality data. Air Commission Control Division Director Garrison Kaufman said the state would like a setup like that of Boulder — but the money just isn’t there.

“If they have ideas on what we should be doing instead, and if someone has dollars for us, we’re willing to take that,” he said.

Colorado’s Untapped Expertise

Petron and NOAA have engaged with Colorado officials on methane in the past. Back in 2014, when she first identified methane data issues, her research group lent air canisters so they could zero in on more accurate values. That led to presentations to officials in charge of air quality about her methane oil and gas research. She’s met a wide range of participants about monitoring including officials from the state, EPA and counties to discuss research conclusions and techniques.

She said it all starts with quality control. In her work, methane samples with errors are identified within hours — not within months. There are layers upon layers of data checks and balances. It all starts with the collection of two air canisters in the field. Lab equipment is tested and calibrated on a daily and weekly basis.

“When we have any type of doubt that a gas may be too high or low, it starts a chain of multiple quality controls on top of what we do regularly for the systems,” Petron said.

State officials don’t appear to follow the same rigorous procedure. By the time the state identified errors with methane values, it no longer had access to the actual canister air. The problems were the result of a data processing error at Atmospheric Analysis and Consulting “that arose after the performance of some routine equipment maintenance,” according to Alicia Frazier, a specialist with the state who is familiar with the issue.

Instead of re-testing the air, AAC readjusted data values “in accordance with accepted statistical practices and standards,” Frazier said. In emails obtained by records request, a representative of AAC said that the uncertainty values surrounding the corrected data are larger compared to other methane values. Some data points simply couldn’t be corrected. But there was no public note or explanation for how or why data points were adjusted.

The end result is data that’s not entirely reliable, Petron said. In reviewing the state’s corrected data, Petron still has questions. Some data points are still lower than South Pole numbers at 1800 parts per billion. She said the data between mid-2017 to mid-2018 still appear lower compared to what is in Colorado’s methane record before and after. There is no scientific explanation for this kind of dip other than inaccurate data.

“This entire mid-2017 to mid-2018 time period is still much lower than what is happening before and after,” Petron said.

That suggests there are still problems that need attention. State officials acknowledge there are still a few data points lower than the South Pole. But John Putnam, head of environmental programs for the state of Colorado, said the state has a different focus.

“We’re not investing the massive amounts that NOAA might have available or some of the other research institutions to finely calibrate that level because that’s not our primary task. Our primary task is to reduce those emissions at the source,” Putnam said.

That means focusing on tracking individual methane leaks from oil and gas wells, rather than putting more resources to tracking the state’s overall emissions. That will help with enforcement against individual operators.

But it still doesn’t tell the state if those crackdowns are getting the state toward its end goal: lower overall methane levels.

To do that, Gabrielle Petron said state of Colorado air quality watchers will have to become more scientific and methodical about how data are collected, stored and managed. Colorado is preparing to implement a bill that requires massive greenhouse gas reductions by 2050. Shaky data on methane could make tracking its success challenging.

Sen. Steve Fenberg is mulling a bill for the 2020 session that establishes an independent scientific review panel for the state’s air quality data.

“It’s a built-in peer review process,” said Fenberg, where scientists review the integrity of the work. “If we’re saying as a policy priority we want to clean up our air, we want to make it healthier to live in Colorado, we need to know where we’re starting from.”

The state has made improvements. It has a mobile lab to measure air plumes when it investigates public complaints. Gov. Jared Polis’ budget request for the next fiscal year asks for $162,000 to fund inspectors and infrared cameras to detect leaks. State officials are planning a large temporary air monitoring effort to gather data on which part of the production process releases the most emissions. As part of this effort, companies will have to start reporting emissions to the state and could use airplane surveys to monitor their emissions

Still, at the moment, the state’s data collection efforts mean it’s impossible to know for sure if Colorado’s crackdown on methane is having an impact. Since methane traps heat most effectively over just 12 short years, time is of the essence. There is no movement to build out a scientific data collection system like that of Helmig or thoroughly incorporate the state’s vast expertise in atmospheric science.

It all adds up to a painfully slow pace for Petron. She can’t help but think of her daughter in the car she drove around the oil fields more than a decade ago. Back then, she was an infant. Today she’s in middle school, about to become a teenager.

In the meantime, the state is taking baby steps and “dabbling” when it comes to air quality and climate, Petron said.

“If we want to take ourselves seriously we need to be responsible and accept that there are better ways to do things,” she said.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to clarify that Gabrielle Petron works for the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, which is affiliated with NOAA.