Ninety-two-year-old World War II veteran Gerald Bennett lives by himself in a San Antonio apartment community made up of seniors. His place is small but homey. Newspapers cover the coffee table, and family photos take most of the shelf space in the living room.

"I like the independence of having my own place and doing my own thing," Bennett said.

He's considered moving to an assisted living facility but doesn't think it would be a good fit, at least for now.

"You are conformed to the things that they do," he said. "I don't feel that I need the kind of help that a lot of people in assisted living need."

Sometimes, isolation will creep in. His wife died several years ago, and his children are scattered across the country. So he's thankful for the companionship of Gloria Estrello, a volunteer with a new Department of Veterans Affairs pilot project.

The five-city pilot is called the Choose Home Senior Corps program. It was created by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Corporation For National and Community Service, a federally-funded agency that also administers the AmeriCorps program.

Besides Bennett's home city of San Antonio, the program is underway in Colorado Springs, Colorado; Las Vegas, Nevada; Glendive, Montana and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

"I have nobody down here, no relations," Bennett said. "If it gets a little lonely, if I feel like I'm getting depressed, I'll give Gloria a call. We'll talk."

Estrello, 70, lives in the same apartment complex. She cooks, cleans, shops, and exercises with Bennett. She also keeps his children updated about his health.

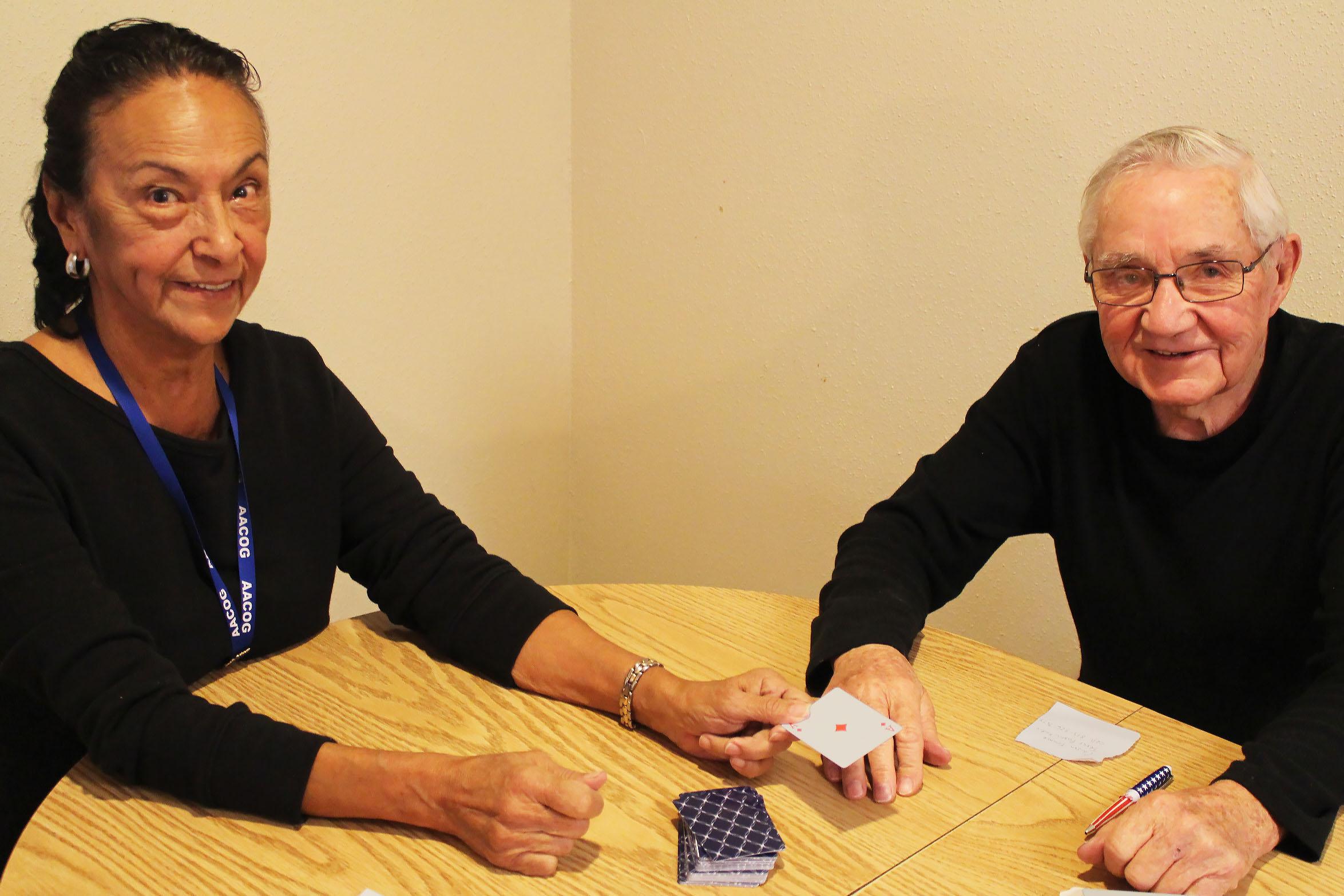

On a recent afternoon, the two played seven cards rummy at Bennett's kitchen table over coffee. Estrello said her arrangement with Bennett, in place since early 2019, has helped her feel more connected. Previously, she lived in a bigger house where her family often gathered.

"I was in a house where I had yard work to do," she said. "Grandkids came over. Then I came over here and it was different. No yard work or activities, in other words."

Carol Lillegard, Bennett's daughter who lives in Vermont, said Estrello has been a godsend.

"She seems to have radar for what his needs are and looks out for him pretty well," Lillegard said. "We've had moments where he's not felt well and needed to go to the emergency room. Gloria's been right there with him. She'll text me and let me know what's going on blow by blow."

VA invested $2 million in seed money to recruit and train about 200 volunteers over 55 to help in veterans' houses. CNCS estimates the volunteers will serve approximately 600 households over a three year period.

Some of the veterans already rely on primary caregivers to help with daily living tasks. Others just need a little bit of help and companionship.

"There have been many, many, many studies on how, when you're isolated, a lot of chronic things can come up with your health," said Kelley Gallant, who coordinates 15 Choose Home Senior Corps volunteers in San Antonio.

The program is part of a broader VA effort to keep veterans out of institutional care. Scotte Hartronft with the VA's office of geriatrics and extended care said initiatives like Choose Home cut costs and try to honor veterans' wishes.

"As technology improves and medical care improves — and people live longer — how can we respect them and honor their preferences to remain in the home as long as it's safe to do so?"

The veteran population, like the rest of America, faces a long-term care bubble. The VA's annual costs of nursing home care have risen to almost $6 billion. By 2024, that number could top $10 billion, a sizeable chunk of the department's budget.

VA Undersecretary Teresa Boyd told Congress last February that as veterans age, approximately 80 percent will need long-term services and support.

"There's an urgent need to accelerate the increase and the availability of the services since most veterans prefer to receive care at home," Boyd said. "VA can improve quality at a lower cost in that setting."

Still, keeping veterans at home longer can put a burden on family caregivers, usually wives, children, or younger siblings. In those cases, volunteers can mean the difference between a veteran being institutionalized or not.

"Sometimes the caregiver will get burnt out and prematurely, they'll have to put them a nursing home," Gallant said, "and they don't want to have to do that."

Gallant hopes the pilot will expand. She said in San Antonio, the demand for volunteers outpaces supply.

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans. Funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2020 North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC. To see more, visit North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC.9(MDEyMDcxNjYwMDEzNzc2MTQzNDNiY2I3ZA004))