Published 12:45 p.m. | Updated 5:44 p.m.

High prices at hospitals are driving the cost of health care up more dramatically in Colorado than elsewhere in the U.S., according to a new state report released Thursday.

The report on cost-shifting comes as Gov. Jared Polis and his administration battles with hospitals over how to rein in health costs, a fight that promises to get even more heated as the legislative session unfolds.

Top Polis health officials contend that hospitals — and the cost to get care at them — are mostly to blame for the state’s ballooning health costs. They say hospital operating expenses in Colorado in 2018 were 14 percent higher than the national average.

Lt. Governor Diane Primavera said, on average, Americans pay twice as much for healthcare compared to those from other developed nations but only enjoy "middle-of-the-pack results" and the lowest life expectancy in the developed world.

"So the question is. If all the money we spend on healthcare isn't making us healthier, then where is all the money going?" Primavera said.

It’s a view hospital leaders vehemently deny. Instead they say a complicated mix of factors, including the state’s high cost of living and competitive job market, help inflate hospital costs as well.

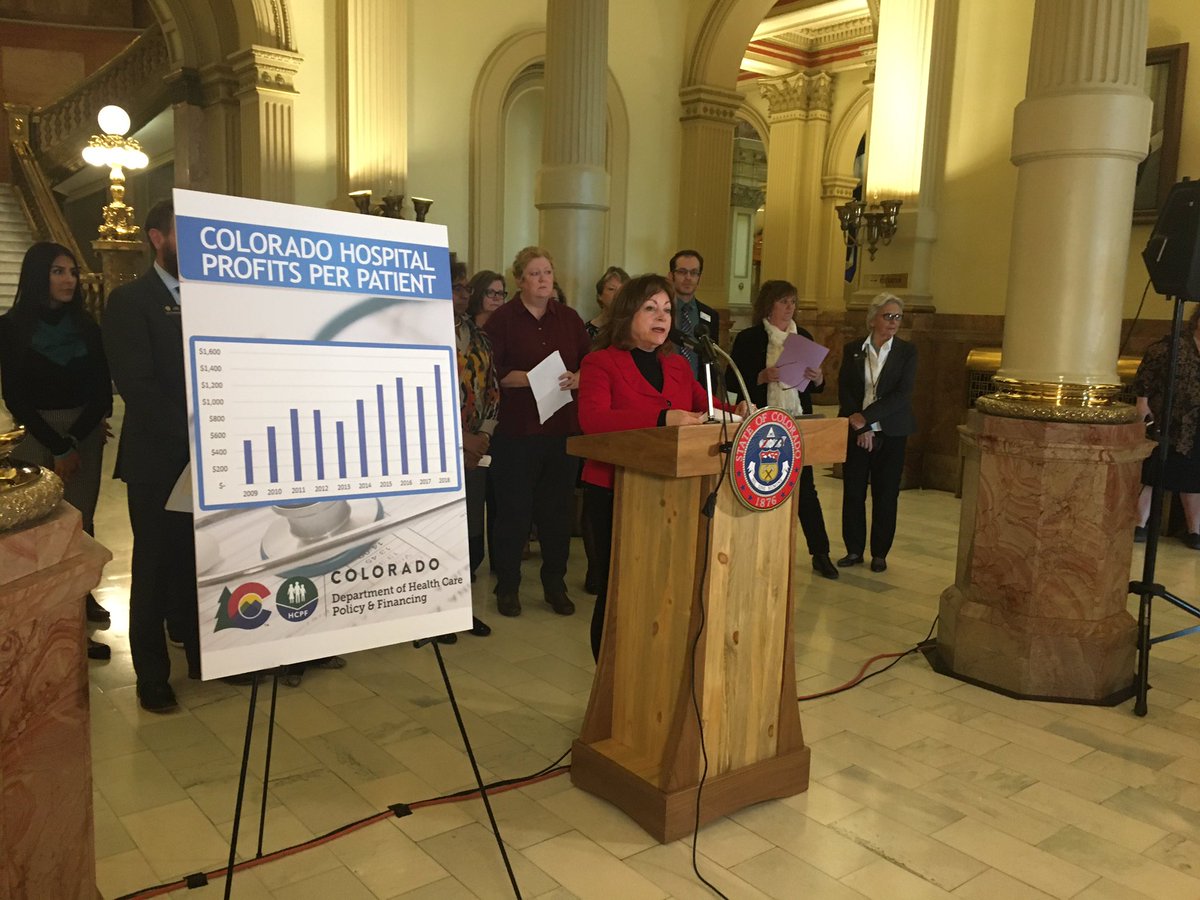

The report found hospital profits shot up by more than 280 percent between 2009 and 2018. Profit per patient rose to more than $1,500 a patient, more than triple the figure from a decade earlier.

The study, by the state’s Department of Health Care Policy and Financing, also reports uncompensated care in Colorado — care that hospitals give but are not paid for — is at historic lows. A fee on hospitals, as well as the launch of the Affordable Care Act, cut the number of uninsured in the state in half. It found hospital financial losses due to charity care and bad debt had plummeted by more than $385 million a year since the state implemented the ACA's Medicaid expansion. That program covers low-income Americans with health insurance.

The state report concludes that it’s not shortfalls in public insurance, but “strategic hospital decisions” that are driving the high costs. In essence, the state says hospitals are shifting costs onto privately insured patients, and profiting to the tune of billions of dollars.

Increased funding from public, taxpayer-backed programs aim to reduce private insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs, but those savings are not being enjoyed by consumers and employers, according to the report.

Hospitals have maintained that the shift in costs to privately insured patients happens because public insurance programs Medicare and Medicaid reimburse hospitals at rates well below what the care actually costs hospitals.

"Cost shift exists because of chronic underfunding of state and federal public health care programs – namely Medicare and Medicaid," said Julie Lonborg, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Hospital Association.

Lonborg said the government payers that cover less than what it costs to provide care now serve more than 60 percent of Coloradans who get care in a hospital.

"The aging of Colorado’s population has driven significant growth in Medicare, which now under reimburses hospitals by 30 cents for every dollar spent on care," she said.

Lonborg conceded that hospitals have improved profit margins over the past year, but said that was due to the state's strong economy and unprecedented population growth.

The state's numbers do not take into account many expenses such as taxes, hospital-owned physician practices and training the next generation of providers, she said.

"This report is distracting from the unintended, yet predicted, consequences of the state’s own policies," Lonborg said.

She said the state’s reinsurance program – touted by Democrats as saving consumers 20 percent on average – caused prices to increase for some consumers, and now the state is trying to force hospitals to pay $40 million one year early. She said that had the potential to endanger the care hospitals provide statewide.

"Colorado hospitals’ losses last year from Medicare and Medicaid hit a record $2.5 billion dollars," pointed out Dan Weaver, vice president of communications at UCHealth. "The report shares that charity care has decreased, which is accurate, as more people are eligible for Medicaid. But their announcement leaves out hospitals’ significant losses from Medicaid under-reimbursements."

He said for UCHealth alone, uncompensated care losses last year reached $367 million, double the number 2015.

But the state’s report claims Colorado’s Medicaid program, called Health First Colorado, has steadily increased payments over the last decade.

“Hospitals could have been passing on significant savings,” from reduced charity care costs and increases in Medicaid payments, to privately insured consumers and employers, the report says.

If hospital costs in Colorado more closely matched national averages, the state could have saved patients more money, it adds. But the report says costs at Colorado hospitals "far exceeded" those elsewhere in the U.S.

Pamela White, a former investigative reporter from Longmont, described a long and difficult recovery from breast cancer.

"I am grateful that I received the care I needed, but it came with a life-altering cost. I couldn't work for a year, although I had insurance. I paid an enormous sum out of pocket. I spent my entire life savings and burned through my retirement," White said.

Since then, White's premium has continued to go up and last year she paid about $15,000 out of pocket in medical bills and the bulk of that was my premium.

"I was paying more than the cost of my mortgage just to have access to healthcare," she said.

White noted that happened just as Colorado hospitals were reporting the second healthiest profit margins in the nation.

Kim Parfitt, a retired public school teacher from Lakewood described similar frustration. She said her retirement package includes health insurance, but premiums are paid out of pocket and the plan has a very high deductible.

Last fall, she ended up in a local emergency room to treat a virus and slight dehydration and was released after two hours of basic treatment. Parfitt said she was shocked when she received a bill with an out-of-pocket amount due of nearly $5,000.

Because of her very high deductible, she will have to pay that entire amount. A call to the hospital's financial assistance office didn't help. The most surprising charges were $650 facility fee and $7,000 facility fee.

"I worry that as my retirement has only just begun, this is likely not the last time I will need hospital care," Parfitt said. "This is out of balance with what the average citizen like me can afford. I wonder what that will mean for me and others like me as we age?"

The report comes as the relationship between Polis, a Democrat, and hospitals, is getting more contentious.

In his annual State of the State address, Polis pointedly singled out hospitals over high profits as the state’s health care costs continue to rise steadily. Polis said Front Range hospitals took in more than $2 billion dollars in profits in 2018. He blamed them for “already using those profits from overcharging patients” to run ads against potential public option legislation. The administration has been exploring that proposal as a central strategy to “save families money.”

It would utilize private insurers to offer every Coloradan health insurance. Officials say it will be cheaper because it lets the state set payment rates and requires insurers use more of the money they take in for actual medical care — not profits.

And to add to that controversy, the Colorado Hospital Association has sued the administration over payments to the fund that pays for Colorado’s reinsurance program. That program basically acts as insurance for insurance. It reimburses insurers for covering the highest-cost patients out of a fund hospitals pay into.

One hospital CEO agrees with state leaders on the need for change, but not the solution. “We've got a problem. We've got to make health care more affordable, more accessible and more transparent. So with that, I agree that we've got to find solutions,” Centura Health President and CEO Peter Banko told CPR in an interview.

But Banko said he worries a public option proposal, one that could include government price controls, is the wrong direction. Banko called for more collaboration on all sides.

"Price is only one small part of the equation," Banko said. "We've been able to partner with health plans and deliver greater savings and more affordability.”