Inside a busy microbiology lab on Colorado State University’s foothills campus, the quest for a coronavirus vaccine has already begun. Ever since a sample of the coronavirus arrived mid-February, researchers have worked eight-hour days in full white protective gear, sometimes wearing respirators.

“For our lab that’s what we live for,” said postdoctoral virologist Izabela Ragan. “I know a lot of labs are excited for the opportunity.”

Ragan and other researchers at Colorado State University have focused attention on using a Mirasol machine, a white box the size of a printer to render the virus inactive. That’s the first step toward creating a vaccine. Over the next six to eight months, they’ll turn to tests of the potential vaccine on small rodents.

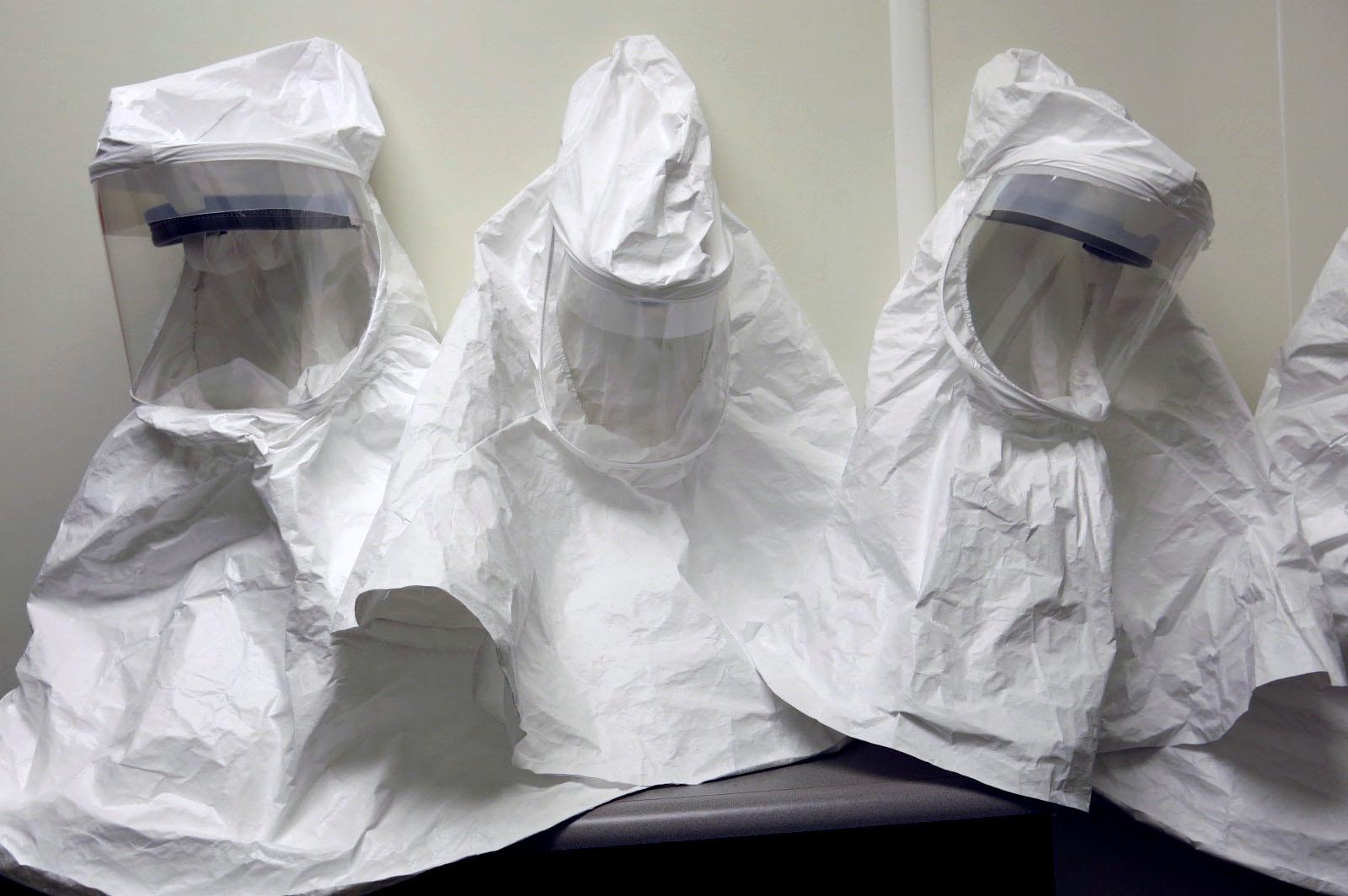

Here’s what it takes to be a virologist: Ragan and others wear head-to-toe white protective gear when they’re in the lab working with the virus. After leaving the lab, they have to shower head to toe if they need to leave it in a small utilitarian stall before walking into a public hallway. The lab itself has filtered air so the exhaust from the lab doesn’t release viruses outside the room. Even animals tested in the lab live in heavily filtered cages.

“Nothing goes out of this filter,” said CSU Biosafety Director Bob Ellis pointing to the ceiling of a mock lab at the university used for training. “So it protects the environment around you, too.”

CSU won’t allow reporters into the actual lab where the coronavirus is, but they did allow reporters into a duplicate training facility.

Vaccine research can take years to develop a successful dose. CSU Vice President for Research Alan Rudolph said the soonest a vaccine can be developed for coronavirus is 18 months. That includes about 6-8 months of animal testing followed by trials with humans, heavily regulated by the Federal Drug Administration.

Rudolph and his colleagues are trying to better develop vaccines in the future. They’re asking questions like, What if researchers could one day develop a vaccine that covers multiple strains of influenza instead of just one? Or, what about manufacturing a vaccine not from a giant facility, but from a bunch of small 3D printers across the country?

“That’s really what we need so we’re not waiting a year and a half for the next vaccine,” Rudolph said.

Stopping the spread of a deadly virus is one research prong at CSU. Understanding why some viruses, like coronavirus, make the jump from animals to humans is another. The hunt is on right now to understand where the coronavirus emerged.

Read more: What does a quarantine look like?

Microbiology professor Richard Bowen has looked extensively at how animals spread viruses to humans. He studied how camels shed the Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome. He also set up an artificial barnyard in the lab to replicate how birds spread the avian flu. That translated into ducks and chickens and rats “running around happy” in a small lab to replicate conditions where the virus emerged.

“And we’ll do more of that--trying to see, do the animals in the cages below become infected more readily than the cages above and that kind of thing,” Bowen said.

He knows the virus originated from Wuhan China, possibly from a so-called wet market where live animals are sold. Now that the virus is inside a CSU lab, Bowen is keen to study which animals are susceptible to the coronavirus. That could lead to understanding how the virus jumped between animals and eventually became contagious to humans.

Based on the genetic sequence of the coronavirus, Bowen said it appears to have possibly come from bats.

“Whether it came from bats in that market, or whether there were two or three animal reservoirs in between, who knows?”

That’s where coronavirus research questions lead to answers, which eventually create more questions on campus.

Ultimately, CSU Vice President for Research Alan Rudolph wants to supercharge research in some of the university's labs with the help of federal dollars. CSU is one of many institutions that submitted grant proposals seeking a piece of the $8 billion federal coronavirus bill. An answer is expected in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, researchers like Izabela Ragan will continue diligently working in the lab to find a vaccine.

“It’s evolving every day of how we can do better with the testing, diagnosing people, understanding how quickly the virus spreads. Every day we’re getting better technology, we’re getting more successful, we have to be better for the next one as well,” she said.