The first weeks of March are often a sprint for political candidates in Colorado. With a deadline looming, campaigns race to collect the thousands of signatures needed to guarantee themselves a spot on the primary ballot. It’s retail politics at its purest.

“That last week, that last six days, that’s the time that you normally would have just hit hard,” said Ken Drew, campaign manager for Democratic state Senate candidate Maria Orms.

March isn't so normal anymore.

The coronavirus outbreak grounded campaigns just as the March 17 signature deadline approached. Voters are unwilling to pick up pens, and volunteers are hesitant to ring doorbells. One state House candidate — Pastor Terrence “Big T” Hughes — is quarantined after a COVID-19 diagnosis, according to his family.

“There has been much speculation already as to how the virus was contracted. Speculations abound, but I dare not speak with any certainty regarding the collection of petitions or any other political functions,” wrote Reginald Holmes, Hughes’ co-pastor.

Hughes was hospitalized with pneumonia and intubated last week, according to a statement released by his family. It was a sobering reminder that COVID-19 is especially threatening to the older people who are often most involved in party politics.

Campaigns grind to a halt

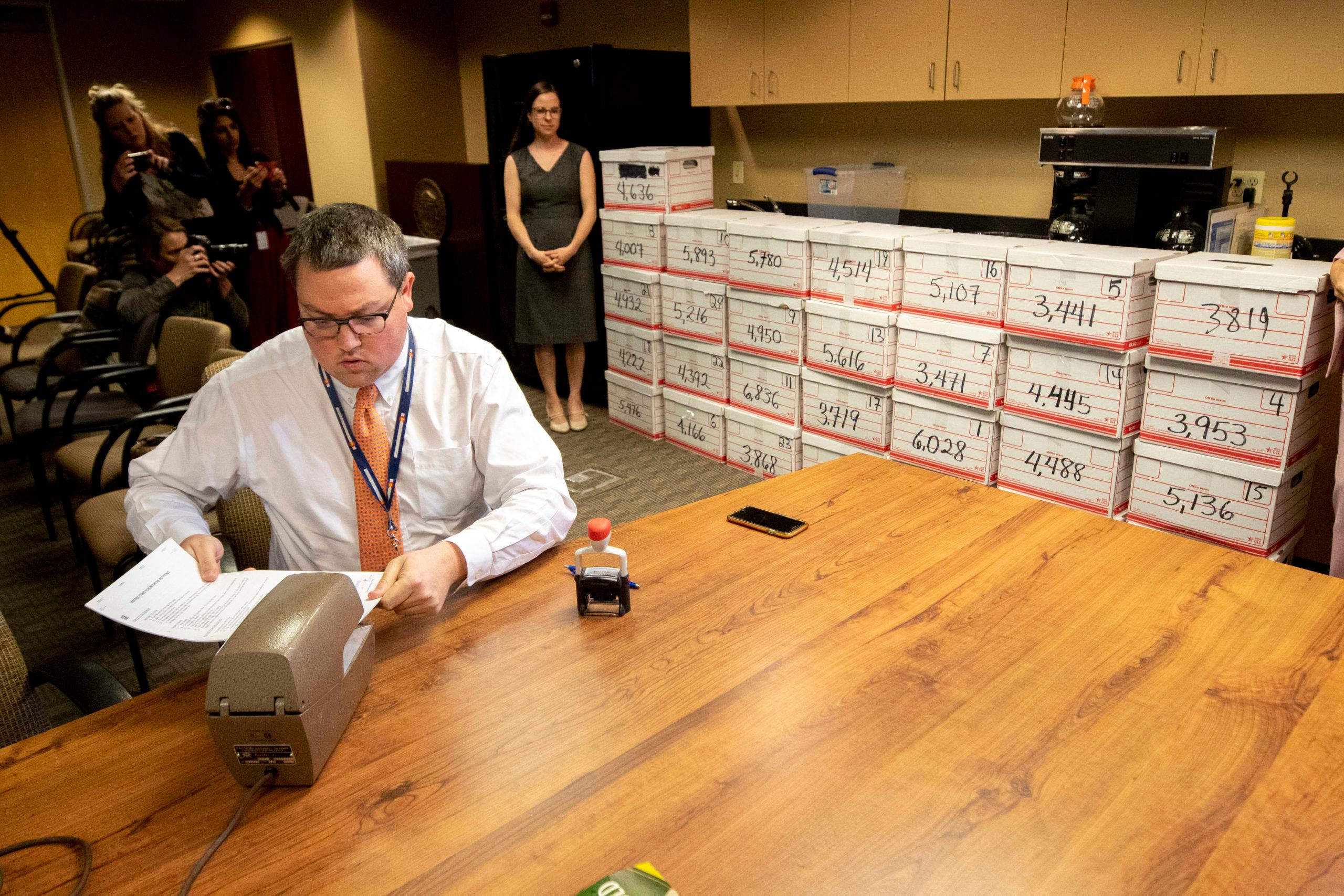

Signature gathering is one of two ways to make the state ballot. Candidates can also try to win support at party political meetings throughout the state. The parties are moving many of those assemblies and conventions to virtual formats, but the state hasn’t made any changes for the signature process.

Still, some campaigns — including Orms’ — canceled signature gathering with a week or more to go. Drew said the thinking was, ‘“OK, if we keep this up, either someone we’re paying is going to get sick, or one of our volunteers, or one of these elderly people opening the door.’”

The campaign still thinks it got the 1,000 valid signatures it needs to make the ballot, although with less room for error than Drew would like. Others aren’t as confident.

“I didn’t get the threshold of what they are asking,” said Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Diana Bray, who called off her volunteers in the final two weeks of the eight-week signature period. She needed 10,500 valid signatures from across the state.

“I’ve been campaigning for a year and poured my own life and heart and soul into this, and of course I was thinking that this was going to make it very tough to make it on to the ballot,” she said of her decision to freeze her signature drive.

“But I just couldn’t be complicit” in putting people at risk, Bray added.

Former Gov. John Hickenlooper turned in his signatures early and has already been certified by the Secretary of State for the U.S. Senate primary ballot. At the same time, he withdrew from the caucus-and-assembly process, citing “ongoing public health and safety concerns.” That leaves the assembly lane open for rival Andrew Romanoff, who has been dominating in that process, and perhaps opens space for another candidate to also win enough delegate support — 30 percent or more — to make the ballot.

Asking for a solution

Bray knew she was short of the requirement, but she turned in her signatures on Monday regardless. She’s hoping that state officials will change the requirements in light of the outbreak.

“How do you measure what 120 people would have done in two weeks?” Bray asked.

She wants the state to allow all candidates onto the primary ballot, and then institute a “ranked choice” system. That would give more power to the voters, she said.

Drew, of the Orms campaign, wants the state to simply lower the signature requirements to reflect the shortened gathering period. The current approach is unfairly damaging candidates who take the signature route, he argued.

Others have suggested extending the signature deadline. It was part of the conversation among state lawmakers and the Secretary of State’s office last week, but lawmakers didn’t ultimately address it.

Instead, they passed a law that allows the parties to hold virtual assemblies and conventions. That will allow one branch of the primary process to continue uninterrupted but it’s no help for candidates who decided to take the signature route instead.

Romanoff said on Tuesday that the state should lower the signature requirements -- a change that wouldn't apply to his campaign's route through the state assembly.

"Although we didn’t take that route, I believe it would be unfair to penalize candidates who did. The pandemic impeded signature gathering," he tweeted. He suggested that the courts of the legislature intervene.

House Majority Leader Alec Garnett disagrees that the caucus-and-assembly candidates would have an advantage. The legislature focused on the assemblies because they were “large group settings” that attract older people and pose a greater public health risk.

Garnett said that suggestions for changing the signature requirements are “a fair question, and I think that we can sort of have a discussion about that.”

But the time for that may have run out. The signature requirements are set by law, and since the legislature has done nothing to change that, Tuesday remains the deadline. Secretary of State Jena Griswold’s office said she hasn’t advocated “one way or another” about changes to those requirements.

“I think everyone’s focus is getting through today’s candidate petition deadline safely,” wrote spokesman Steve Hurlbert.

What is the future for campaigning?

The shutdown could also reshape the race toward the general election.

One big question is what this will mean for ballot initiatives. Campaigners want voters to weigh in on subjects from housing growth to criminal justice, and they also need signatures to get on the ballot. Eight different initiatives are potentially at the signature-gathering stage right now, and others are earlier in the process.

“There’s two sides of it: Everybody’s home. But I don’t know how many people are answering their doors at this point,” said Michael Fields, a conservative organizer for a proposal to restrict the state legislature’s use of fees.

Canvassing companies are still offering to work, according to Daniel Hayes, who wants voters to approve growth limits on the Front Range. He’s in talks with a contractor whose workers travel with hand sanitizer, and he thinks that the anti-development initiative will be appealing “because, frankly, I don’t think people want a ton of people coming here” amid a pandemic.

But with his signatures due by early June, he only puts his odds of making the ballot at 50-50. “I think it’s a great time to do it, but who knew this was the year this would happen?”

State economists hope that the worst of the virus’ impacts will pass by the summer, perhaps leaving time for a normal fall campaign. But the candidates are gearing up for an unusual season.

“Whatever we do, it’s not going to look like traditional politics. You’re not going to be able to knock on doors, kiss babies,” Drew said. “What does a virtual campaign look like?”

The Democratic Party, he suggested, should be working on the infrastructure for online-only debates and other adjustments.

Editor's note: This article was updated with Romanoff's comment.