Doctors and nurses who work in hospital emergency rooms and intensive care units are trained to anticipate the next crisis, and to consider that one day a major pandemic like the 1918 flu could sweep across the world.

But the coronavirus has tested those assumptions, and added unforeseen pressures on health care workers, forcing them to reinvent the way they do their jobs.

Families have always been a mainstay in hospital rooms, gathering around a patient’s bedside. But the rules designed to prevent the spread of COVID-19 prohibit visitors, turning nurses and doctors into substitute friends and family as well as caregivers.

“Families are helpful to our patients,” said Courtney Hoffbauer, a nurse and director of acute care services at Memorial Hospital in Colorado Springs. "Just them being present (in the rooms) really impacts (them).”

With that familial presence missing, nurses and doctors have taken on that role to varying degrees, spending extra time with patients, holding their hands and trying to ward off loneliness. It’s also led many hospitals to develop innovative ways for families to continue to play a role in a patients’ recovery, Hoffbauer said. Technology has been the great connector.

“One of the things that we learned early on is that it's important for our patients to hear their family's voices, if nothing else,” Hoffbauer said. “So we have put in place where we have a nurse that goes into every single patient's room with an iPad, and families can speak to their loved one.”

If a patient is on a ventilator and can’t talk, this allows them to at least hear a loved one’s voice.

The Medical Center of Aurora has had to adapt to a no-visitors policy too, said Dr. Joseph Forrester, a critical care physician and pulmonologist who works there. The hospital is among those in the metro area that have treated the most COVID-19 patients.

The Aurora hospital’s intensive care unit has 38 beds, but served 50 ICU patients earlier this week. That meant opening up two other parts of the hospital and converting them to ICU beds, Forrester said. He says of his 30 years practicing medicine, this has been the longest stretch that he’s seen so many patients with such acute needs.

“It puts a lot of strain on everybody involved, from the housekeepers to the nurses to the physicians, when it's sustained to this degree,” he said.

Forrester has seen family members drop patients off at the ER without knowing if or when they’ll see them again. And now that doctors can’t talk to families in person, Forrester said conveying complex medical information over the phone has been particularly challenging.

“We're trying to express how sick they are, how much equipment they have on them (and) give them some idea of prognosis,” Forrester said. “And I think it's quite difficult for our families to go from having someone at home doing relatively well to being critically ill, and then being unable to see them in that transition.”

Doctors have often described the rapid decline that can come with the virus. Patients can be sick but doing relatively well one minute only to be gasping for breath the next. And doctors and nurses across the country have expressed the heartbreak of being the only person in the room with patients who don’t survive.

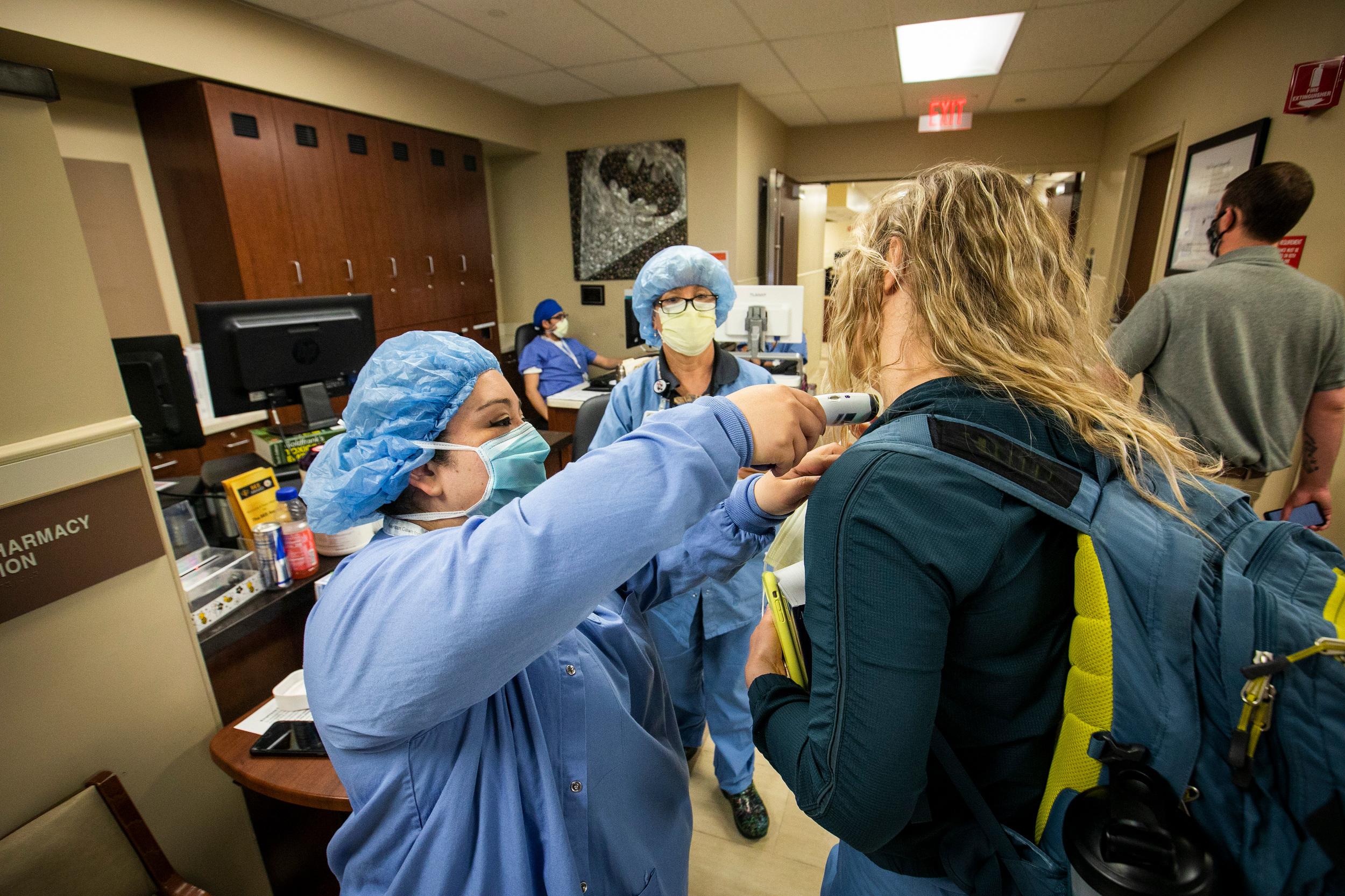

Forrester also says along with being a conduit between patients and their families, there are extra steps medical staff have to take these days to do their jobs. Dozens of times a day, they’re required to put on and take off protective gear when going from room to room. That slows their efforts to care for multiple patients.

Forrester said, fortunately, Colorado hasn’t run into a situation like New York where it's been short ventilators, though many hospitals here have lacked adequate protective equipment like masks and gowns and have had to use them multiple times.

The Medical Center of Aurora and other Colorado hospitals have been given a respite of sorts in recent days, with the number of patients dropping.

Now, there’s a new factor for health care workers to consider as Gov. Jared Polis lifts the state’s stay-at-home Monday. Many wonder if the easing of restrictions will accelerate the spread of the virus and lead to another sustained period of very sick patients in the hospital.

“I appreciate a soft opening, and I appreciate us easing into this to try to get a handle on ... what the next few weeks is going to look like for us,” said Courtney Hoffbauer, the nurse at Memorial Hospital in the Springs. “We want to make sure the community is safe.”

Many nurses and doctors say they are cautiously optimistic.

“We're members of the community ... and we feel the same stresses that everybody else does financially and personally and emotionally,” said Dr. Dylan Luyten, medical director of the emergency department at Swedish Medical Center. “So I think it's fair to say that ... we welcome the opening of the economy.”

Luyten says he recognizes the change will probably result in some increase in the total number of sick patients they see. But, he says, Colorado hospitals are much more prepared today than they were before the crisis.

“I think now we have a lot more experience and understanding of our ... ability to (handle a) surge and develop backup plans of care,” he said.

Luyten said he expects a lot of “waxing and waning” of the state rules over the next few months.

Hoffbauer said she’s learned a lot over the past month or two and has been reminded why she went into nursing years ago.

“There is not another profession I could ever imagine myself in,” she said. “The ability to take care of the community ... when there is such a need has really been humbling and a privilege.”