Coloradans have plenty on their minds between protests, the pandemic and — in some cases — an upcoming primary election. In fact, those three ‘p’s don’t stand alone. They’re intertwined in the politics of the moment.

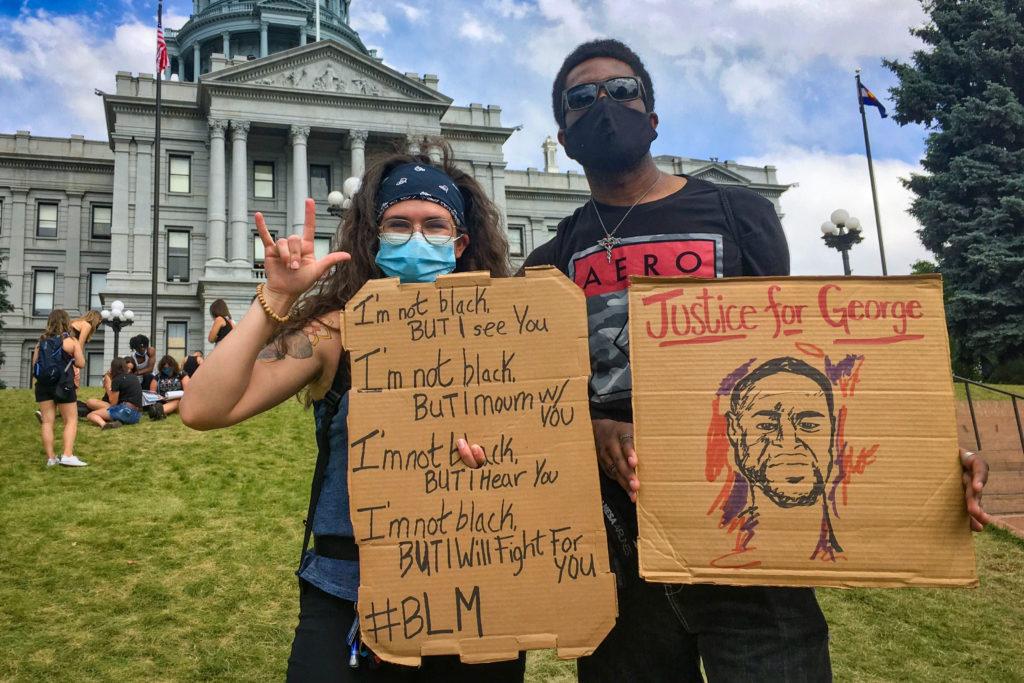

After the death of George Floyd, Gabriel Lavine came out to lend his voice to the Denver protests against police brutality. As he stood on the steps of the state Capitol, Lavine drew a line between the demonstrations and the nation’s health system.

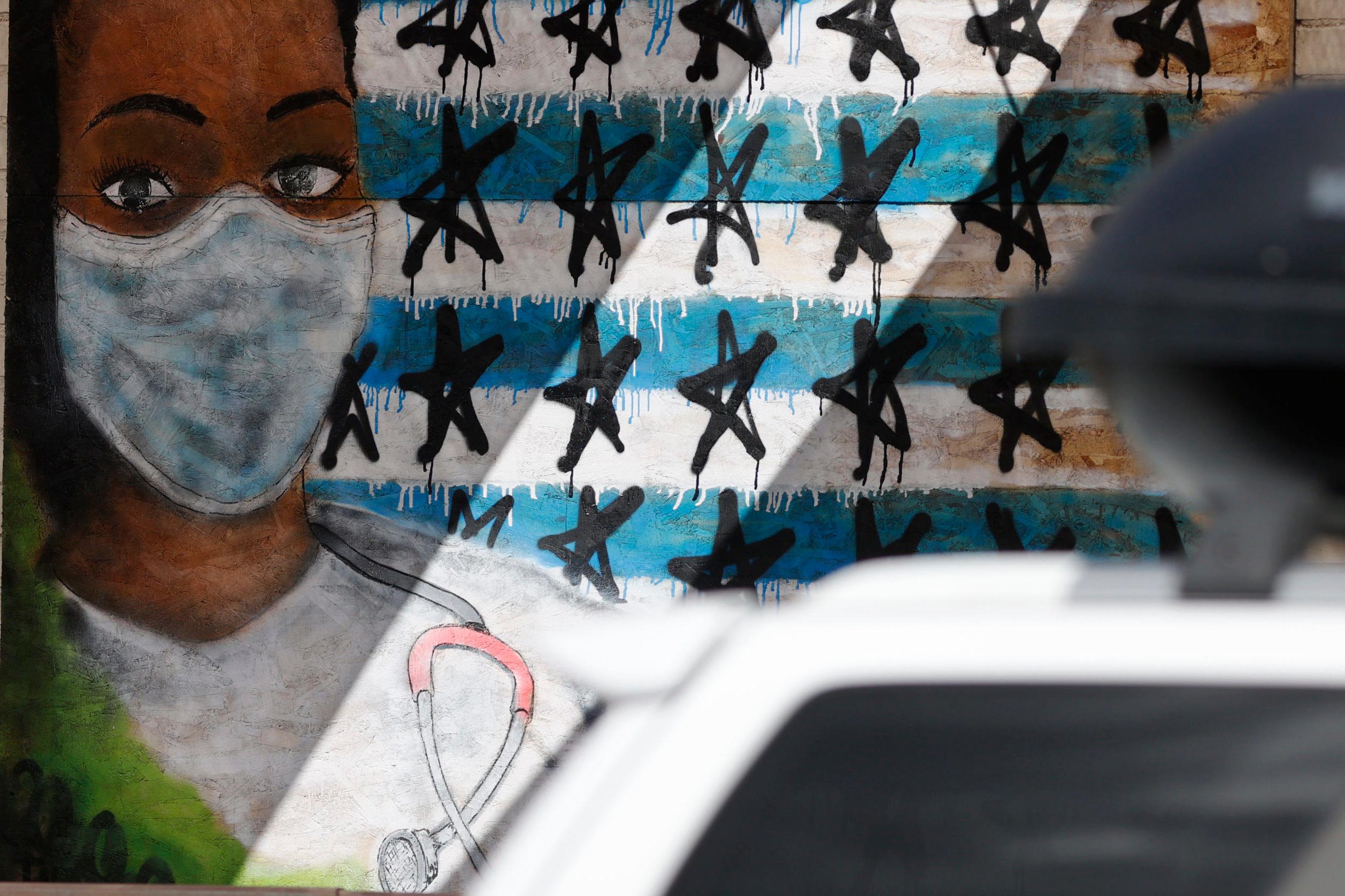

“Why are our cops decked out in protective gear, but we can't find a mask for nurses?” he said. “There's no reason those many nurses should have died when I'm literally staring down the barrel of a gun on the opposite end of somebody decked out in plastic. That makes no sense to me.”

Lavine moved to Denver from Louisiana last year to look for a job in education. In the meantime, he started to drive for Lyft until “COVID ate all of that up.” When asked what he’s doing for health insurance, he replied that he doesn’t have any.

“I hope I don't get sick,” he said.

Even as people take to the streets, Colorado is in the midst of a primary race to decide the Democratic candidate who will challenge Republican Sen. Cory Gardner for the Senate. Both hopefuls, former Gov. John Hickenlooper and former state House Speaker Andrew Romanoff, say the pandemic has made it clear how urgent health care is.

In their final debate before the June 30 primary, Hickenlooper said that “Health care is a right — it’s not a privilege and we've got to get to universal coverage.” The governor wants to build on the success of the Affordable Care Act and pursue a public option. Romanoff is a proponent of Medicare for All, an idea popularized by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, that would make the federal government the single-payer of health insurance.

“We ought to fight with all our might to provide a system of universal health care instead of allowing the broken model subsidized by the insurance industry and the politicians on its payroll to leave a quarter of the population uninsured or underinsured,” Romanoff said in the debate. “That was never a great idea. During a pandemic, it's a disaster.”

Even though they disagree on how to tackle health care, both candidates want the same thing that Lavine wants: expanded coverage and universal health insurance.

“We've seen various countries around the world execute it,” Lavine said. “I think the only thing holding Americans back right now is greed. We know it can happen. It's just getting the people in power to wake up to the reality of the situation.”

Voters like Ken Devilbiss, a computer analyst from Brighton, say they’re following the ongoing debate over health care carefully. It’s a major concern for him and “it's either number one or number two on almost everybody's list” that he’s spoken to, including his family.

Devilbiss is a moderate Democrat. He’s also 65 and on Medicare. He blames the administration with “fumbling” the health response to COVID-19 from the beginning.

“Ninety percent of the people I talk to say that that is going to be a defining issue in how they vote. We're the ones that are up against it, you know, there's no two ways about that,” he said.

For other voters, the pandemic has reinforced their political views. Johnny Davis lives in Divide, west of Colorado Springs with a view of Pikes Peak. Both the 59-year-old and his wife work in health care imaging producing X-rays, MRIs and CT scans.

The coronavirus had a major effect on him due to his work with hospitals which have seen “a reduction in hours and a reduction in staff,” he said. “The revenue for our hospital system just dried up. And so now we're starting back up and it's time to catch up.”

Davis is a conservative and thinks both incumbent Sen. Cory Gardner and President Donald Trump have done a good job.

“[The pandemic] doesn't change my thinking because I think he's still the best candidate for the election, for the next term. I think that a lot of this COVID, there's been a lot of overreaction and a lot of overreach by the government.”

Hugh Fowler, a former Republican state senator from south Denver, sees it the same way. Fowler is 94 and founded a pair of charter schools. He credits Trump for shutting down travel from China early and defends the administration's handling of the pandemic.

“I don't think that it's going to have that much impact on the election simply because there are other things that have always been more important and because it's a complex issue.”

As Fowler sees it, the president has been thwarted by “deep-state” bureaucrats, Democrats out to make him look bad and a hostile news media. He thinks the Affordable Care Act was a disaster and is all-in to reelect Gardner and Trump.

“It's the economy, stupid,” he said, quoting an old political maxim attributed to former Bill Clinton campaign strategist James Carville. “If the virus thing settles down so that [Trump’s] own economic record, which is just overwhelming, can become the campaign issue then there won't be any question about the campaign. Health care won't mean anything.”

In conversations with other voters, plenty of them question whether the pandemic has changed many people’s views.

Lori Brooks, a 50-year-old college professor in Littleton, considers herself a conservative. She is firmly in the camp that considers the shutdown orders to limit the spread of the virus as overreactions; she called “the cure worse than the disease.” At first, she understood the need for more stringent measures but once it seemed like the curve had been flattened, “the governors really really went too far in my opinion in the shutdowns.”

A more significant issue for her regarding health care is the Trump administration’s move to unwind Obamacare, including backing a federal lawsuit that would gut the law. She thinks the administration’s moves helped her.

“Me personally, my company's insurance offerings, the deductibles, have gone down and my premiums have gone down. So it's gotten better,” said Brooks, who is an unaffiliated voter.

After the launch of the Affordable Care Act, Brooks said her doctor decided to switch to concierge coverage, where a patient pays a doctor an annual fee for care. His patient load, including those on Medicaid, got too heavy, and she said she “would've lost my doctor.” She’s paying $1,800 a year and said she has “really great access to my doctor now.”

Brooks is happy with the administration and with Sen. Gardner.

“My personal politics is that the federal government, other than Medicare, should not be involved in people's health at all,” she said. “The Democrat agenda with health care seems to be going into more of a single-payer direction. I’m definitely opposed to going in that direction.”

Views of the government's role seem to be at the heart of things for many voters.

If you were to ask 21-year-old Mahala Benson, one of the protestors out on the streets in Denver, you’d get a very different view than Brooks or Fowler. She said coronavirus has only amplified her view that basic health insurance should be available to everyone.

“Now with this pandemic, I do hope that it kind of ignites a fire under a lot of people's butts that a lot of people don't have insurance or can't afford the top-notch doctor to help them take care of themselves,” she said.

Voters will have their say soon enough, either in the June 30 primary or in November.