Fifty years ago, on a clear October afternoon, a plane crashed on a tree-studded mountainside above Interstate 70 near Silver Plume, killing nearly the entire first string of the Wichita State University Shockers football team.

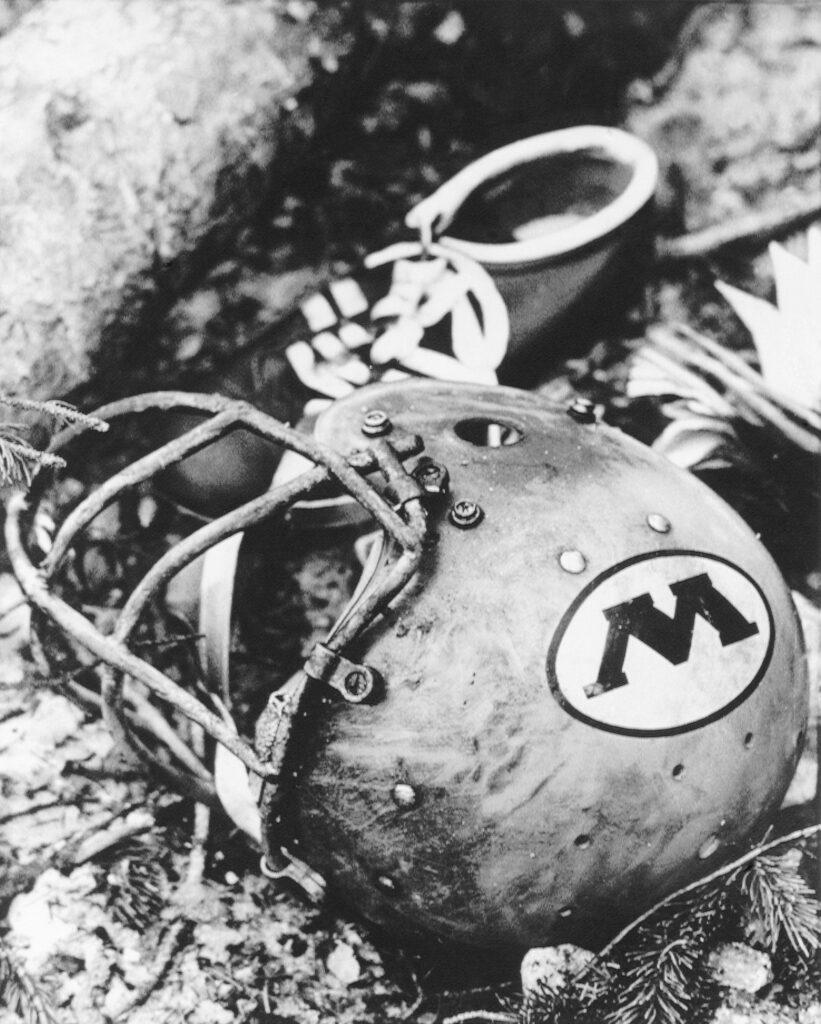

A Denver TV reporter described the scene as melted gold football helmets and cleats strewn over the burning ground, and a “solemn silence” in what he referred to as a “holocaust of death.”

Twenty-two-year-old Rick Stephens, WSU’s noseguard and one of only nine survivors, was thrown from the plane as it belly-landed. He survived because he was ejected away from an ensuing explosion.

Just before the crash, Stephens had left his seat to check the cockpit, sensing that what he was seeing out the window didn’t seem right.

“We were on even elevation with old mine shafts and rusted equipment. When I got to the cockpit I realized the pilots were in a panic mode trying to determine a possible passage-way through, given our elevation,” Stephens told Colorado Matters. “I turned and there was no blue sky. I felt a sharp bank to the left or right. The wings were hitting the trees. I was knocked unconscious. The next thing that I knew I was outside of the aircraft some 25 yards and spitting out gravel and teeth, trying to make some sense of what had happened.”

Stephens’ leg was broken and his hip was dislocated. He watched from yards away, helpless as the plane caught fire, killing his teammates who were trapped by their seatbelts and underneath the wreckage. Three construction workers who saw the crash while they were working on the nearby Eisenhower Tunnel carried Stephens down the mountainside.

“They risked their lives,” he said. “The plane was beginning to become engulfed in flames. They picked me up and carried me 100 yards. It was very difficult moving in that terrain downhill.”

Some players were able to crawl out of a hole in the plane and walk to the highway where surprised drivers in oncoming cars took them to area hospitals.

On Saturday, Oct. 3, 2020, Stephens, 72, started a 500-mile bicycle ride from Wichita, Kansas to the Eisenhower Tunnel. His goal is to reach it by Oct. 10. From there, he will then hike to the crash site with relatives of some of those killed in the crash to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the accident. His aim is to raise money for a program that pays for descendants of the victims to attend WSU on scholarship.

“There is a memorial scholarship that funds tuition and some support for the survivors’ children, as well as those who perished. So we'll have an opportunity to gain some support for that scholarship, which both of my children and others benefited from.”

The Second Plane Took A Different Route

The WSU football team was on two planes, named for the school colors: the Gold plane carried the first team starters, team support and boosters who had won the trip to Utah State for selling the most amount of tickets.

The Black plane carried coaches and the second string players. After a stop in Denver’s Stapleton airport for refueling, the Black plane flew north, while the Gold plane’s pilots made the fatal decision to take the scenic route west past Georgetown toward Loveland Pass.

“It’s a tremendous, vast increase in elevation which everybody familiar with the area knows,” WSU historian Craig Minor said in a Kansas Public television documentary about the crash. “So of all places to fly, ...that was maybe the worst (place).”

The Black plane arrived safely and on schedule to a tarmac filled with reporters in Logan, Utah. These were the days were long before the internet and social media and those on board didn’t find out immediately what happened. It wasn’t until their coaches left the plane, were debriefed and returned that they learned the Gold plane had crashed.

“You could have heard a pin drop,” passenger Gus Griebe said in the documentary. “What happened? When do we find out? How bad is it?”

NTSB Investigation

Stephens spent weeks in a Denver hospital and was eventually transferred to Wichita where he recovered, even testifying as a witness before the National Transportation Safety Board from his hospital bed.

“The pilot who survived was never held accountable. He continued to deny he was responsible,” Stephens explained of the investigation. “He blamed it on the other pilot and was never interviewed by the NTSB.”

According to the official report, the “probable cause of this accident was the intentional operation of the aircraft over a mountain valley route at an altitude from which the aircraft could neither climb over the obstructing terrain ahead nor execute a successful course reversal. Significant factors were the overloaded condition of the aircraft, the virtual absence of flight planning for the chosen route of flight from Denver to Logan, a lack of understanding on the part of the crew of the performance capabilities and limitations of the aircraft, and the lack of operational management to monitor and appropriately control the actions of the flight crew.”

Life After the Crash

There was little counseling for the Gold plane’s few survivors, as they, the remainder of the team on the Black plane, and the city, attended funerals.

Three weeks after the crash, the WSU Shockers, reduced mostly to freshmen and sophomores, returned to the football field to finish out the season with zero wins.

Stephens said one of the nine survivors, Randy Jackson, went on to play professional football and died of pancreatic cancer in 2010. Some who are still alive, he said, don’t get involved and some have moved away from Wichita.

As a teacher, coach and high school administrator, Stephens said he lived his best life for those who couldn’t. He’ll spend his time on the long bike ride thinking about the people who shouldn’t have died in the mountains of Colorado on Oct. 2, 1970.

“Marking 50 years which have passed in your life, your time is a great mystery,” he said. “I've tried to do some things with my life that would benefit others. I feel like I've accomplished that.”