Fifty-four-year-old Lupita’s alarm clock goes off at 6:00 a.m. It’s still dark outside.

She immediately starts to cook eggs and gets cereal out for her first guest, who’ll arrive in about 15 minutes.

The silence of her home will soon be broken by the shouts of three preschoolers, one of them her granddaughter. They’ll be under her care for the next 12 hours. Then Lupita will clean the house for an hour or two and finally fall into bed.

Lupita has taken care of children from her home in the Roaring Fork Valley for 19 years. She asked CPR News to not use her full name to protect her identity.

The valley has hundreds of homes just like hers, where mostly Latina women take care of the children of the workers who travel to Vail to make up hotel bedrooms, to Snowmass to clean hot-tubs, to Beaver Creek to prepare tourists meals. The demand for more early childhood training is surging in the Latino community, from high school students in the Roaring Fork Valley to elders like Lupita. Advocates say Spanish-speaking caregivers could be a significant piece in strengthening Colorado’s early child care workforce pipeline.

Lupita is part of Colorado’s growing network of informal child care known as “friends, families and neighbors.” These are grandparents, aunts, uncles, neighbors and friends that provide free or inexpensive care, usually in homes, outside of Colorado’s system of about 5,000 licensed facilities.

Licensed child care is too expensive and is in too short of supply for many Coloradans, especially in rural parts of the state like the Roaring Fork Valley. So home-based child care blankets the landscape, taking care of an estimated 57 percent of the state’s children, according to the Colorado Children’s Campaign.

“They provide a really valuable service in caring for kids where there's either no access to child care, or it's financially out of reach for a lot of families,” said Molly Yost, director of early childhood initiatives for Mile High United Way.

The state has a goal of increasing the cultural and linguistic diversity of child care providers. A survey of nearly 5,000 early childhood education workers found half the teachers worked in classrooms where they didn’t speak the same language as the children. Almost two-thirds of language mismatches occurred where children speak Spanish and the teacher did not. In addition, Latina teachers were less likely to be lead teachers and in leadership roles than their white counterparts.

In Colorado, there are no standards nor statewide coordinated training efforts for home-based child care providers, either to recruit them, retain them or simply increase their training so children have better outcomes. Yost said the handful of training programs that exist are reaching only a fraction of the state’s informal caregivers.

“We know that when providers are more prepared and have the tools and the resources that they're more likely to be successful and continue following their passion which is caring for young children,” Yost said.

Though it's changing, Kenia Pinela of Valley Settlement, a nonprofit in Carbondale, said there is still a black cloud when people talk about informal child care, something akin to “don’t take your children there. They’re not safe.”

If child care systems were designed to support low-income families by offering affordable child care that meets the needs of parents who work two jobs or who work night shifts, Pinela argues, there wouldn’t be a need for informal child care.

“We can’t blind ourselves to what is really out there,” she said.

More than half of informal caregivers in Colorado are Hispanic or Latina, the vast majority are women and two-thirds live in the metro area, according to preliminary results from a survey of informal caregivers by Mile High United Way and the University of Denver’s Butler Institute for Families.

Forty percent of home-based caregivers earned less than $25,000 a year. COVID-19 has further depressed incomes. Seventy-three percent of Hispanic or Latina providers saw their incomes drop, compared to 33 percent for white providers. Most white providers had health insurance, while only 39 percent of providers who identify as Hispanic had health insurance.

In 2010, Kenia Pinela traveled up and down the valley, from Aspen to Parachute knocking on doors.

The Valley Settlement employee was trying to find out where the valley’s young children were. Who was taking care of them while their parents worked? What did families need? What were the barriers to increasing the quality of care?

“We were building relationships, just hearing from families,” Pinela said. “We wanted to know what’s missing, what needs to be done in the community.”

Among hundreds of families surveyed, her team found that 1 percent of children who were eligible for preschool attended it. Why? It was too expensive. There weren’t enough slots. The times didn’t work for families.

In 2018, 51 percent of Coloradans lived in child care deserts, especially in rural areas. These communities have at least three times more children under age 5 than licensed child care slots, with Black and Hispanic/Latino Coloradans more likely to live in these deserts. There is only licensed child care capacity for about 40 percent of Colorado’s young children.

So many turn to friends, families and neighbors.

While Pinela saw many deficits in homes, from a lack of emergency evacuation plans to missing parent contact information, the demand for more quality training from the providers, many of whom are undocumented, was insatiable.

After a few years of trial and error training programs, Pinla got the green light to do nine months of listening to get it right.

“I knocked on doors and I did the best that I could to find providers and just understand them,” she said.

The issue was dear to her heart, she said, because she was raised by a neighborhood provider after her parents migrated from Mexico.

She spent hours in caregivers’ homes to understand the challenges they faced that prevented them from providing the best quality care for children.

“Sometimes they just don't have the resources or knowledge to do the best that they can do,” Pinela said, noting many charge $20 a day per child and don’t have the money for materials or making better spaces for children.

Some providers, like Lupita, tried to take early childhood classes at a community college but they were too expensive and language was a barrier. The other challenge was that classes were in the morning when she had kids to take care of.

Though Lupita has cared for children for almost two decades, she knew she had a lot to learn, “because my way of caring for children was very different from how children are right now, right?” she said in Spanish.

Lupita heard about Valley Settlement from a neighbor but wondered how she could take classes when her informal child care home wasn’t licensed.

“I panicked,” she said in Spanish. “It scared me a lot.”

She was told, of course, she could take classes.

Pinela knew night classes wouldn’t work, with the long hours home-based providers work as parents are traveling from jobs in Aspen and Snowmass. So, the two-hour class in Spanish is on Saturdays. Even that can be difficult as then the women provide care for their children and grandchildren. On occasion, children pop in and out of screens of the Zoom class.

“Our program is designed to be there with them and to coach through the chaos, you know, we like to call it controlled chaos,” Pinela said. “It truly stemmed from what they wanted and what they needed.”

Valley Settlement’s friends, families and neighbors training program provides home child care workers the skills and tools they need to ensure children are in a safe and healthy environment. There are two training programs – one in Eagle and another in the Roaring Fork Valley. The 24-month program includes two two-hour home visits per month from instructors on any given topic.

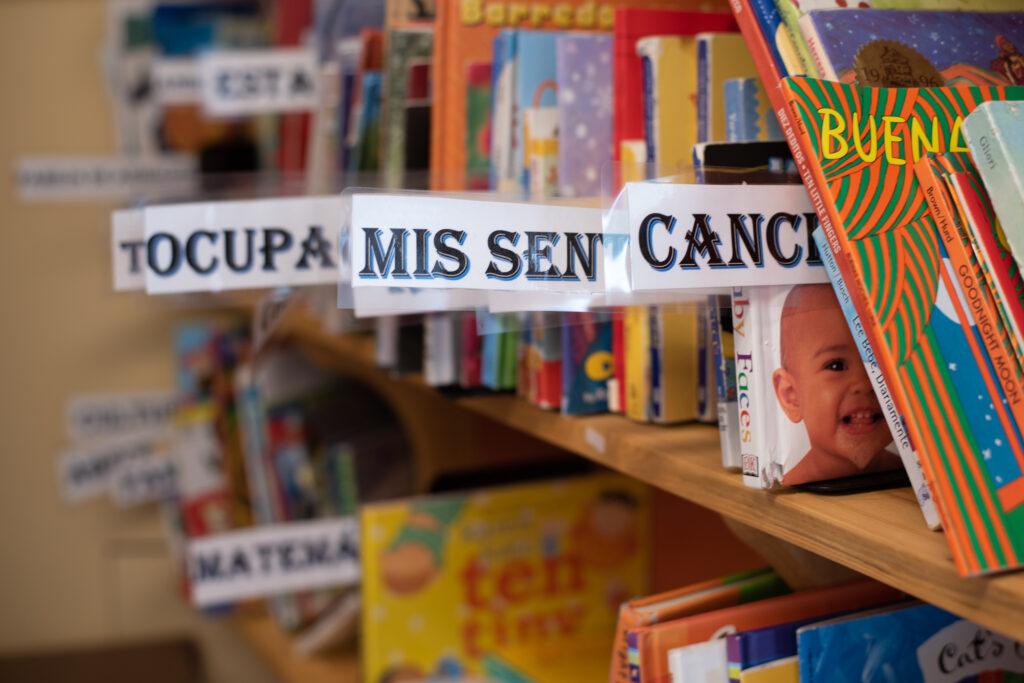

Once a month, Valley Settlement also distributes books, blocks and musical instruments — all the materials needed to stimulate cognitive and emotional development. They’re bought from low-cost places like the Dollar Store and Walmart so women will be encouraged to replace worn-out items.

One recent Saturday Zoom class focused on “safety.” Everything from what to do if a child is choking to the best ways to disinfect.

About a dozen women participated, asking each other questions in Spanish, collaborating and helping each other learn from two instructors. First, the women discussed what safety measures resonate the most with them. In preparation for the exam, they practice short-answer questions like, “What’s the first step if a child suffers a burn?”

“Put the burn under cold water,” one woman said.

“Yes, no ointment, nothing, only cold water first,” the instructor replied.

They get into complex issues like talking to parents about the importance of vaccinations with parents, even those who disagree. And how, even in cold climates with foot-deep snow, it’s important to get the children outside every day.

“When we make it culturally responsive to who they are to their values and to what's important to them, we will start to see those behavior changes,” Pinela said.

Lupita said she’s learned some things she did wrong with her daughters and other children. For example, Lupita learned all about preventing sudden infant death syndrome, by placing infants on their backs to sleep and not using pillows or fluffy comforters as was her custom.

“I want to learn more because the children need it and so do I,” she said.

The class spends two months on safety alone. Other topics are cognitive development, reading strategies, story-telling, math and science. They do intensive units on social and emotional development.

Lupita has learned how to talk to younger children in a way that makes them open up, reflect on how they are feeling, what their mood is like, how things are at home and how to help children regulate their own emotions.

The Valley Settlement curriculum tackles trauma head-on. Sometimes that trauma comes from generations of neglect, of abuse, of minimizing women and the women still carry that with them, Pinela said. The classroom becomes a space where providers can reflect on themselves, perhaps do some healing themselves.

“So that when she's [caregiver] doing emotions and self-regulation, and breathing with the kids, she's already done it with herself and she's already practicing with herself so that she can be a better provider for those kids,” Pinela said.

Sometimes there’s a lot of guilt because the women learn so much that they wished they would've known in raising their own children, like “they weren't good enough mothers.”

It’s an emotional journey for the women to get this training they so desperately want. They come to realize the huge importance and stakes involved in educating young children.

“They were never able to put that into meaning and put that into words because no one's ever valued them for what they do,” Pinela said.

Thirty-two women are in the two-year program which has already graduated 42 providers. Graduates of Valley Settlement’s first two-year cohort all returned to Pinela wanting more.

So, for those who choose, they can continue classes to get the nationally recognized Child Development Associate credential. However, if the women do not have the equivalent of a master’s or bachelor’s in their home country or a GED in the U.S., they can’t get the degree.

“I said, ‘Is this even worth it if you can’t get a certificate?’” Pinela asked the women. “And they said, ‘100 percent, we want to learn. And if I can't get a certificate, that's OK. I just want to learn. I want to be better.’”

A Mile High United Way survey on informal caregivers shows the vast majority don’t do what they do for the money, rather they see a need in their communities or families and they love taking care of children.

Though her Latina providers exit the program with the educational credentials to be licensed, they can’t because many are undocumented. Some experts say a change in state law could pave the way for them to be licensed.

Lupita will finish her course of studies in May. There’s been a lot to read in the two-year course and sometimes her eyes give out.

“But I love it,” she said. “I feel that every time I read something new I want to search for more information.”

Even at 54, she’s learned how to use the computer, download videos and do homework electronically. Lupita, even over the phone, exudes warmth and love for children.

“I am very overprotective with them [her children], making sure they’re all well.”

Parents are often the biggest challenge. They’ll drop their child off at six in the morning and pick them up at six at night and leave the child with just a little bottle of juice. Lupita makes sure the child has food but encourages the parents to bring some fruit, vegetables, maybe a little soup. Others will leave the child with a hamburger.

“I say, “oh no, that’s not proper food for a child!” she laughed.

She tries to educate each parent as best she can, something that is a big part of the early childhood training.

What Lupita likes best about her job though is the children’s affection.

“They are lovely children that fill me with joy,” she said. “I like to be with them, I like to play with them. I like to see how they are learning and teaching each other.”

This story is part of a series produced as part of the Higher Education Media Fellowship at the Institute for Citizens & Scholars. The Fellowship supports new reporting into issues related to postsecondary career and technical education.