Spirituals are often taught to children. I believe that’s because the melodies are simple and easy to learn. The lyrics are repetitious and easily grasped. Many of the spirituals are structured in a call and response manner, ideal for group participation. All of this is true and highlights the African cultural retentions inherent in the music. Still, it does not negate the deeper meanings held in the music, including its historical context.

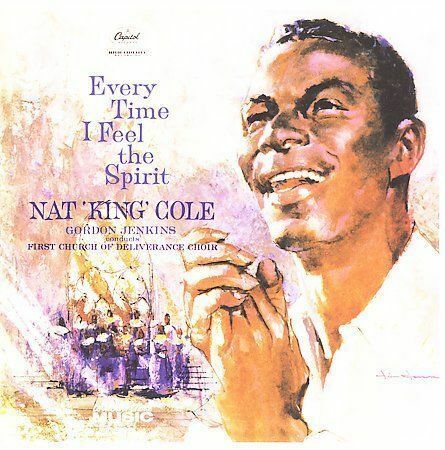

In the song “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” the word “Spirit” refers to the Holy Spirit. To “feel” or “catch” the Spirit harkens back to Africa where spirit possession was not uncommon, especially when people gathered for ritual ceremonies. By spirit possession, I literally mean that the spirit or orisha would inhabit and control the physical body of a human host. Lesser gods known as orishas or ancestors could be summoned using certain rhythms and melodies if a person knew the right songs to play. Those who were willing hosts or predisposed could be inhabited by the summoned spirits and they would behave in a manner that was characteristic of that spirit or orisha.

This tradition was carried on by the enslaved here in the States in a practice called the ring shout, where they would gather and sing and dance in a circle moving counterclockwise. They were careful not to lift their feet, because that could be interpreted as dancing. Dancing was considered a sin by their Christian enslavers. The repetition of the singing and the intensity of the movement and rhythm of the feet and handclaps would drive the participants into a frenzy that would result in spirit possession. In this case, the Holy Spirit.

I remember singing this song, this spiritual, as a child. It would always be up-tempo; spirited and full of energy. Yet as I prepared to write this article, I picked up a copy of a book edited by R. Nathaniel Dett of Hampton University – Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro. This spiritual is included in a section labeled “Hymns of Meditation.” The printed music suggests a moderate, walking tempo and says to be sung “very expressively.” The category of “meditation” and the instructive, performative words “expressively” invoke a different idea from how I am accustomed to thinking about this song and what my experience has been. When one feels the spirit, one jumps, becomes excited, shouts, even to the point of frenzy in the African tradition. But now I find myself reconsidering how I have thought about this spiritual. Take the last part of the refrain within the context of meditation; “Every time I feel the Spirit moving in my heart I will pray.” Prayer. Prayer seems counter-intuitive to “feeling the Spirit,” or at least as I typically think about it. This version in Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro suggests meditation, contemplation, when one “feels the Spirit.” This is more of a thoughtful conversation that involves listening.

Now let’s consider the first verse – “Upon the mountain my Lord spoke, out His mouth came fire and smoke.” This refers to the moment Moses heard the voice of God on Mount Horeb from a flaming bush that did not burn. This would not a be moment of great, passionate fervor. Rather, a moment of thoughtfulness, reverence, and prayer. The subsequent verses:

All around me looks so shine,

ask my Lord if all was mine.

Jordan river is chilly and cold,

chills the body but not the soul.

I see these words with fresh eyes. In the book of Revelation heaven is described as a place where the streets are paved with gold. (Rev. 21:21) The enslaved, not treated well on earth would be welcome and well treated in this beautiful place. This second verse speaks of reverence and awe. The river represents baptism and cleansing, which is welcoming and has significant meaning for the soul. But there’s another meaning - coded words among the knowing. For the enslaved, who escaped captivity (or tried), passing through water helped them elude dogs who might pick up their scent. So, water could literally be the path to freedom.

The songs in Religious Folk-Songs of the Negro were gathered from those who actually experienced slavery or were just a few generations removed. The memories and meanings were intact and fresh. I know enough about this music and traditions and the history to know that African Americans have repurposed these songs, to hold whatever meaning they need them to hold in the moment. Therefore, I don’t need to discard the meaning held from my youth. I can think of this song anew, and “pray” with it for a while. Perhaps, I might feel the Spirit in a different way, and hear or feel something I have not felt before…

M. Roger Holland, II is Teaching Assistant Professor of African American Music and Theology at the University of Denver’s Lamont School of Music, and Director of DU’s Spirituals Project Choir.

Listen to Professor Holland’s monthly musical selections and commentary throughout the year on CPR Classical, including Sunday mornings on our choral music show Sing!, hosted by David Ginder.

February's Spiritual - “Lord, How Come Me Here?”

March's Spiritual - “He Never Said A Mumblin Word”

April's Spiritual - "Ride On, King Jesus"

Hear CPR Classical by clicking “Listen Live” at the top on this website. You can also hear CPR Classical at 88.1 FM in Denver, at radio signals around Colorado, or ask your smart speaker to “Play CPR Classical.”