Driving west from Castle Rock, each rise of the dirt road reveals another hundred acres of open ranchland sweeping toward the green foothills ahead, a vista of long grasses and scattered stands of trees. After a few twisting miles, a handsome gray farmhouse comes into view.

“We’re country folks, and we just love this place out here,” explained Bill Baine, as he sat on his porch in late May, looking out over the homestead that he and his wife, Alice, bought in the 1980s. “When we first got here, there was no homes up there on the hill. It was just us.”

Over their decades here, they’ve grown hay, raised cattle and fixed up the old farmhouse. It’s their hidden corner of the fast-developing Front Range. But this spring, just as the pandemic was fading, they were on the verge of losing it all.

“It’s hard to put into words how a person feels,” said Baine, burly and white-bearded at age 74. “We went through all of our savings. The only thing we rely on now is our income tax refund — which will last two weeks, and I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

Baine had collected unemployment benefits for a year — only to see his payments suddenly frozen in March. He had encountered a glitch while trying to comply with the labor department’s new cybersecurity system, a software platform called ID.me. He was not alone: Dozens of other people had contacted me with similar complaints.

I recently spent a day with Baine because I wanted to better understand how these technical problems are affecting people’s lives, and to see the state’s unemployment software in action. And — after months of covering the ID.me rollout — I also had a hunch about how to solve the issue.

Our experience on that Monday would show why, more than a year into the pandemic, continued glitches in the unemployment system are still disrupting lives. The solutions are often simple, and yet completely out of reach. And it illustrates a challenge that will outlast the current crisis.

'‘I need help.’ ‘We’re sorry.’'

As we talked on the porch, Baine pulled his iPhone from his shirt pocket, slid on his eyeglasses and opened the browser. The screen showed the virtual queue to get his unemployment account unlocked.

“Estimated wait time is two hours and 43 minutes,” he read. The problem was that the wait time never changes.

“That has been like that for over two weeks,” he explained.

Baine lost his job as a tractor driver when his employer, an environmental reclamation company, shut down early in the pandemic. Unemployment benefits had kept him and his wife afloat for nearly a year. But that changed when the state implemented its new cybersecurity platform.

The platform, ID.me, is run by a software company in Virginia, and it’s now a required part of more than 20 states’ unemployment programs. For many people, the ID.me process is simple: They use their smartphones to scan their faces and upload pictures of their government-issued identity cards. The images are checked by a facial recognition system.

When Baine tried, the system wouldn’t accept the images of his face. It told him he’d need to attend a virtual appointment with a “trusted referee.” But he could never get through the line for that appointment, so he tried calling the state’s unemployment hotlines instead.

“Absolutely no help. They say they have nothing to do with this. I go, ‘I need help.’ They say, ‘We’re sorry,’” Baine said.

For months, he said, he was told to “wait his turn.”

It was impossible to know what was blocking his ID.me approval, since Baine wasn’t even getting an error message that hinted at a problem. But I had a simple theory: Baine needed a solid internet connection to make it through a multi-hour queue and a laptop to complete the process.

Unfortunately, he didn’t have either. His property is nearly 10 miles from the development of Castle Rock, so the cost of a wired connection was exorbitant. Instead, he relied on an iPhone and two bars of cellular data.

Testing my hunch would take some driving and a lot of patience. So, I’d brought my own laptop and cleared my schedule. After a few minutes of chatting, we got in Baine’s F-350 and rumbled back down the long dirt road toward the Castle Rock library.

“I know where the bumps are on this road,” he joked as he weaved around the curves.

Baine was skeptical that this plan would work. Just making this drive was a hardship; he could barely afford gas to drive for job interviews and necessities. But he was ready to try anything. He just needed enough money to last until a potential new job was set to start this summer — a couple months.

“But without the help I need from unemployment, I don’t know what’s going to happen,” he said.

One of many

As we drove, Baine explained all the different ways he’d already tried to solve his unemployment problem.

He’d spent hours on the phone. His daughter Irene had driven from Colorado Springs to spend all day working on it. An agent with a state call center had even made Baine an appointment with a county workforce center — but when he showed up there, they had no idea how to help him.

Baine’s far from the only one. Unemployment payments dropped by nearly 40% over the three weeks after ID.me was deployed, and the number of accounts being paid was reduced by about 50,000.

Much of that drop was intentional: ID.me is meant to block scammers who are using fake or stolen identities to claim unemployment benefits. But the process is also cutting off an unknown number of people who don’t have the right technology or the right identification, among other problems.

Call the state help center at 303-536-5615. Agents can offer assistance, refer you to ID.me's support team or, in some cases, book an in-person appointment for users who don't have the right technology. The state also offers ID.me tips on its website.

I’d heard from several older workers like Baine, who face an especially hard time getting rehired, even as the overall job market improves.

“I think they’re jerkin’ people around here,” Baine said of ID.me. “Either it’s too busy or it’s not a big enough company, something like that.”

The state has offered some of his own solutions. About 2,200 people have gotten help with ID.me from the state call centers. If they need access to technology, some are able to get in-person appointments at an office in downtown Denver. A technical change also allows people to use a webcam, instead of a smartphone, to complete the automated process.

But the company hasn’t delivered on another promise of help: Its CEO, Blake Hall, earlier said that a network of in-person verification kiosks would open across the nation on June 1. That still hasn’t happened as of July 6, and even if they do arrive, none are slated for Colorado, because the company’s proposal was too pricey and overly focused on urban areas, according to CDLE officials. (A company official said that ID.me would share more details about the network when it was ready to launch.)

As Baine and I drove away from his rural home, he shared a sentiment that I’d heard many times from others with unemployment problems: The last couple months have left him feeling isolated and helpless.

“You feel kind of left out in the cold,” he said. “If you had a problem, an issue, and no one would help you, wouldn’t you feel kind of bad?”

'This is the way it is all the time.'

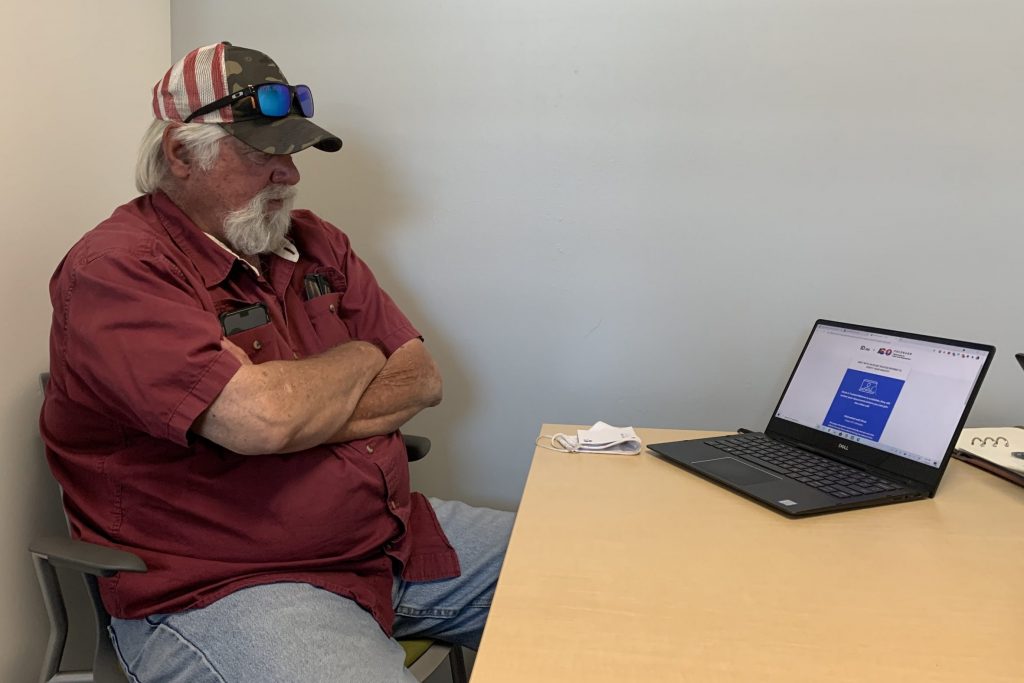

Arriving at the library, we both slipped on masks, unsure what the current protocols were. A librarian quickly got us set up in a cramped study room in the teen section, of all places.

Baine bent his large frame over the laptop and pecked in his password at the ID.me website. Then the problems started: The screen that came up wasn’t one he’d seen in his weeks of trying.

His account’s dashboard said nothing about unemployment. It took us a few minutes to realize that we were in the wrong part of the website; we had to go back in through a specific link from the state labor department’s site, which eventually got us to the right page.

This time, the wait was one hour and 48 minutes to (hopefully) connect for a video interview with an ID.me contractor who could finally verify Baine’s identity.

As we waited, we talked about all the other people who had shared similar problems with me. Paging through my inbox at the library, I discovered a suicide threat someone had sent me the day before, driven to hopelessness by their UI problems. Baine urged me to call the man, and I did. It was the second suicidal email I’d received that week. Eventually, I was able to connect both senders with help.

If you need help, dial 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. You can also reach the Colorado Crisis Services hotline at 1-844-493-8255 or text “TALK” to 38255 to speak with a trained counselor or professional. Counselors are also available at walk-in locations or online to chat.

This kind of desperation felt new to me. Perhaps it’s because, at this stage of the pandemic, people have spent down their resources and don’t see more help in sight.

“It’s very possible I could lose everything, you know,” Baine said, “so hopefully this will work.”

In a way, his fate was tied to the display of hours and minutes on the screen. And, soon enough, it changed. The timer quietly ticked down by a couple minutes. This was a win: The numbers had never changed at Baine’s house. Maybe his unreliable cellular service had been subtly screwing things up.

But he wasn’t ready to celebrate: “I ain’t buying it.”

And it soon appeared he was right to be skeptical. The timer suddenly went back up, and then down again. Its fluctuations were maddening. At one point, after hours of waiting, the timer reverted all the way back to 1:48, our starting point.

“No, I knew it wouldn’t work,” Baine told me, “but I appreciate you trying. This is the way it is all the time.”

The three-minute solution

This story, though, does have a happy ending. After some tinkering and refreshing, the timer finally started going our way again, and quickly. It passed 90 minutes, then 60, and then 30, dropping by a few minutes at once. I noticed Baine getting more excited, and even nervous, his foot tapping as we got under 10.

“I’d be able to make a house payment, pay electric bills, get to work,” he said.

He wondered aloud what would happen when the timer ran out. Would someone appear on the screen, he asked? After weeks of frustration, would he give them a piece of his mind?

The timer hit one minute, and then an anticlimactic zero.

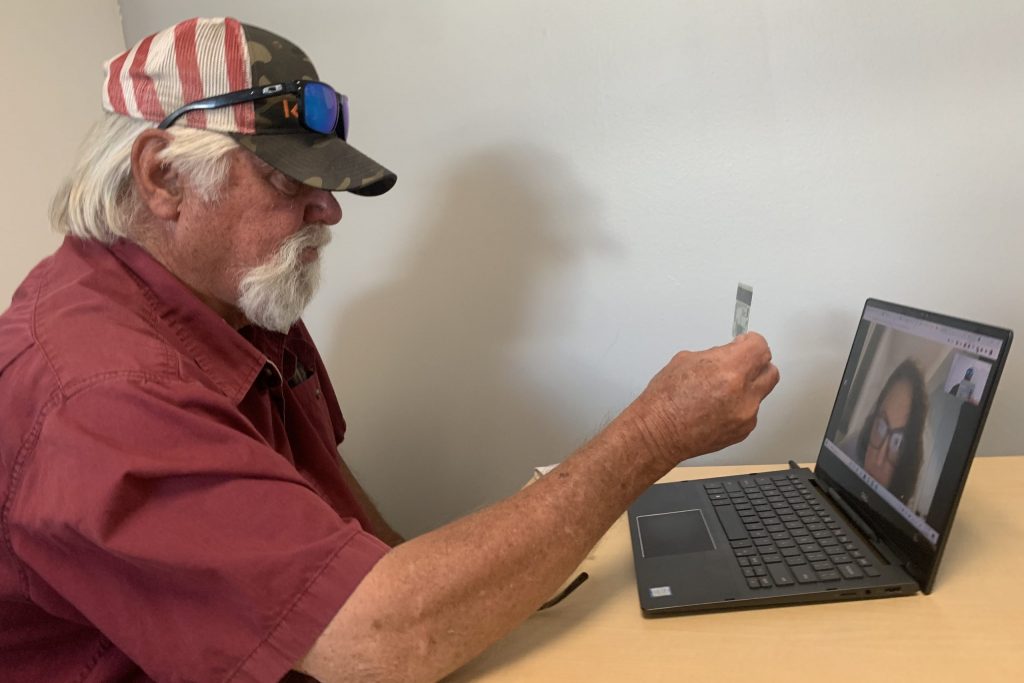

Finally, someone did appear — a woman in her home office replacing the timer.

“Can you hear me OK?” she asked, and they exchanged pleasantries.

She had Baine hold up a copy of his driver’s license to the camera and recite some of his personal identifying information, including his social security number. She was checking that there was a real person who matched the information and photograph that was attached to Baine’s account — exactly what the automated technology had failed to do months earlier.

After months of waiting, it took about three minutes.

“Well, thank you for your patience,” the contractor said pleasantly. “This completes your ‘trusted referee’ video call.”

As he logged off, Baine looked as if he didn’t know how to feel. “It’s weird, Andy,” he laughed.

The solution to his problem was simple in execution — all it took was a modern computer and a solid internet connection. But that was totally out of reach for him and many other people.

About 15 percent of the U.S. population doesn’t have a smartphone, and even more lack a computer, according to Pew Research. As governments and companies embrace tech-reliant biometric services like ID.me, this kind of problem is likely to continue long after the pandemic.

There’s another element: Besides simply lacking the technology, he’d been unable to get a single, human answer about what to do next — which had left him increasingly unable to navigate a complex system. This journey to the library was a risk, a potential waste of time and gas for a man running short on both.

Back on the road, Baine thanked me warmly — but he wondered about everyone else, all those increasingly desperate messages in my inbox, the people I wouldn’t be able to spend hours with.

“What about all these other people?” he said.

By the time we got back to his place, a thunderstorm was rolling over the foothills. His wife was out running errands, so he called her from the front yard. “We got that handled. I gotta do a few more things, but then we’re good,” he said.

A few days later, he let me know his benefits had been unfrozen. He thinks it’ll be enough to last until his next job — and to keep the couple living in their quiet corner of the Front Range.