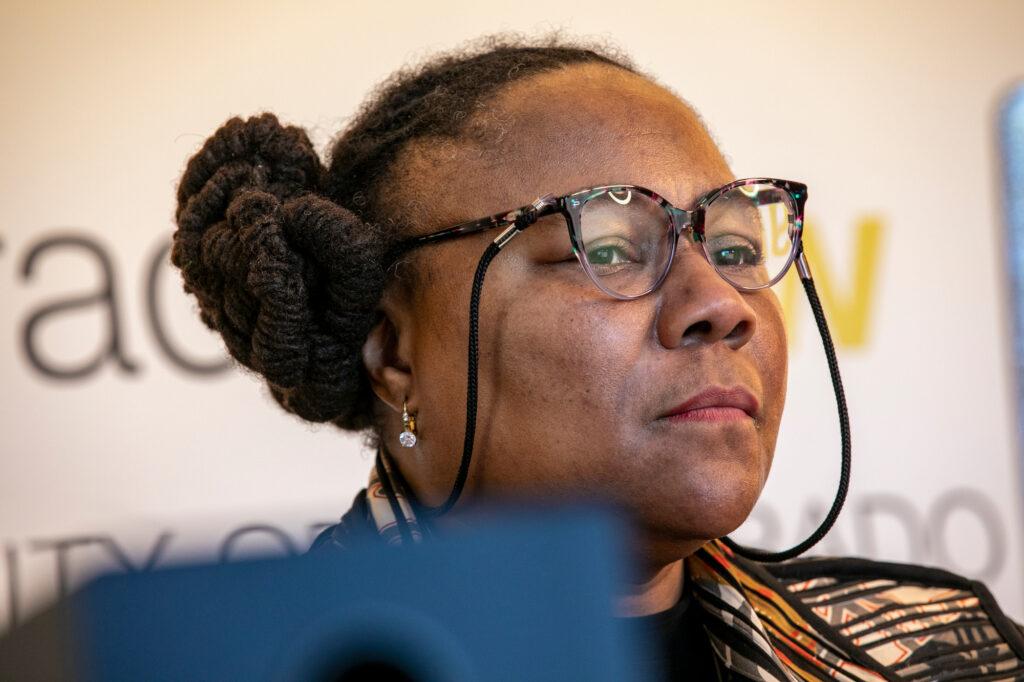

When Lolita Buckner Inniss moved to Denver earlier this year for her new post as Dean of Law at CU Boulder, she spent some time walking around the Five Points neighborhood, often referred to as “The Harlem of the West.”

As a native of Los Angeles, she had never been there before, but she said “it felt so familiar that it was positively creepy.” That’s because her grandmother had been born there more than a century ago and she grew up hearing stories of those streets.

And Inniss’ family tree extends even further back in the Denver area. Her great-grandfather was a member of the 116th Colored Infantry and served at Appomattox during the Civil War.

“He had heard that Colorado was a wonderful place for recently freed enslaved people,” Inniss said, so after the war, “he headed out this way and he and his family were here for the next half-century or so.”

A path to the law

Inniss moved to Colorado from Dallas where she was Senior Associate Dean of Law at Southern Methodist University.

She has worn many hats during her career. She has experience as a prosecutor and a defense attorney. She is a legal scholar and professor with expertise in property law, legal history, legal geography, feminist theory and critical race theory. And, she’s an author: her book, “The Princeton Fugitive Slave: The Trials of James Collins Johnson,” came out in 2019.

As a child, Inniss said she was drawn by an innate proclivity to the realm of Reason.

She was the sort of child who wanted to know why, exactly, she was told ‘no.’

“I wanted a full understanding of the reasoning that they had entered into in order to reach ‘no.’ I also wanted to understand whether and when I might get a ‘yes.’ And what were the conditions that I might change that would make ‘no’ into a ‘yes.’”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, she was often chosen to play the judge in school programs. But while Inniss’ personality and intellect were geared toward the law, she didn’t see people around her becoming attorneys or judges.

“The first time I actually knew and had any sort of relationship with an attorney was when I got to law school at UCLA,” she said. “They were not in my family. They were not in my community. And so I had a lot to learn.”

She did, however, know people from a young age who had run-ins with the law.

“I came from a very working-class, poor family,” she said, “who also sadly had too much in relationship with law and the criminal justice system.”

One incident in particular sticks in her mind.

When she was six years old, she was living with an aunt, the aunt’s 10 children and several other cousins while her mother spent some time putting her life back together after a divorce. Innis’ oldest male cousin, Junior, was also living there. Even though he was just a teenager, he was the de facto head of the family. For money, he worked as a house cleaner for another family in the predominantly white semi-rural neighborhood of Pomona, CA.

One day, Inniss recalled, “the police came and said that my cousin had been accused of raping the 13-year-old girl who lived in the house.”

It was the first time Inniss had heard the word “rape.” She didn’t know what it was and no one would explain.

“It was apparently something that happened to girls or women. I figured that part out,” she said.

But she couldn't square it as having anything to do with Junior.

“This was the kindest, gentlest person you could ever meet,” she said.

Junior was not arrested that day, but the police came a lot and the family went to court a lot. It was the first time she was aware of other people judging the family because of their race and socioeconomic status.

“I had this real feeling that the justice system didn't value and certainly didn't respect people like us.”

She said the charges against her cousin were unsubstantiated and eventually dismissed. But the events shaped Inniss’ sense of justice.

“For my young mind,” she said, “justice meant just showing up over and over again and hoping that nothing happened to you. And as I got older, I felt I wanted more control over justice or at least the processes of justice.”

Critical race theory

Inniss knew from a young age that race could factor into a person’s experience of the justice system. So, one of the many topics she taught when she became a law professor was critical race theory.

It’s become a loaded term these days, but Inniss said, it’s not well understood. She said, at the root, it’s simply about critical thinking: “We're really asking people to loosen their embrace on the idea of universal norms. That doesn't mean that the things that we've been declaring as truths for a millennia aren't true or aren't accurate, or aren't useful approaches. It means that we're now going to question them.”

For example, she said, the criminal justice system uses the binary of guilty or not guilty. If we applied critical race theory, she continued, “we would ask ourselves, does it make sense to structure a justice system with this really rather rigid binary that doesn't necessarily explain what goes on?”

That kind of critical thinking, she said, absolutely has a place at Colorado Law, and at all places of higher learning.

Feminist legal theory

Inniss has come to value another critical lens through which to view the law and legal history: feminist legal theory.

Much like critical race theory, “feminist legal theory asks us to think about the norms, the substance, the process of law” that apply to women, Inniss said. The theory asks people to consider, “how, if at all, are women participating, or I might also say not participating, in these processes?”

And she said there are often intersections between the ‘woman question’ and the ‘race question.’ She gave the example of a legal case from the 1960s out of East Cleveland, Ohio

The suburb of East Cleveland, she explained, was experiencing ‘white flight’ in the 1950s and 1960s as Black families — often headed by women — moved in.

“The city decided that they did not like what was happening. And so they passed a law that created this incredibly arcane definition of family, meaning if there were children in the house and grandchildren, you had to be directly related to them in ways that only genealogists perhaps could understand.”

The Black woman in the case was living in a family arrangement that violated that city law.

The case eventually went all the way to the Supreme Court.

“Often it's cited now for what the definition of family is,” Inniss said. The case also serves as a reference to “whether municipalities can make laws that interfere with familial living norms and structures.”

“The idea that a woman, a grandmother, a parent would need or want to gather family around her in a way that's often common in women-headed families — that probably would have been useful in the discussion of that case,” she said.

Yet, the case was not talked about in terms of women or race.

“So feminist legal theory, and indeed, also critical race theory, invite us to ask questions.”

COVID and the law

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised new questions about laws and the legal system, Inniss said. One such question is whether hearings and trials need to happen in person. That was a norm that made justice “inaccessible” to some, she said.

“The fact that the COVID-19 pandemic has caused some courts and other tribunals to open up to remote hearings,” she said, “I think that's tremendous. And I think some of that stuff is not going to go away for the simple fact that if we can admit more people into these processes, if we can get through them more quickly, then we are actually doing justice.”

But remote courts quickly get complicated, she admitted, because when you bring the courtroom into your home through your computer screen, “you're bridging boundaries. You're breaching geographies.” And that can blur the lines between rules that relate to one space versus another.

That very phenomenon has also affected students of law, said Inniss — many of whom have had to adjust to remote learning over the last year and a half.

Diversifying the law school pipeline

The experience students have of their law school education is important to Inniss. And so is the diversity of the students who are privileged to get there.

She talks about her work at the law school to almost anybody who will listen — especially young people, whom she hopes she can inspire to pursue careers in law.

She speaks fondly of a five-year-old neighbor who she sometimes sees walking around the block.

“I'll stop and I'll talk with him,” she said. “And I'll say, ‘I had an interesting day at work.’ And he'll say, ‘what did you do?’ And I'll tell him in very simple terms, and he gets it.”

“This is the thing,” she continued. “When we think of law, we think of law with a capital L. But law is what happens on the playground. Law is when six kids see a stray ball and one of them says, ‘Hey, I see a ball.’ And the second one says, ‘I'll bet I can get it first.’ And he runs fast and he gets it. And you know what? Oddly enough, that's the state of the Common Law about who would get the ball as well! I mean, we're doing law all the time.”

That’s what she tries to point out to everyone she meets, whether they are considering a legal education or have never seen the law as relevant to their lives.

“Pipelining has to do with having those conversations,” she said. “It’s about reminding people of what law is, so that it's not so remote from them.”