Gov. Jared Polis is getting pushback after saying the new recommended name for a mountain in Clear Creek County, Mestaa’ėhehe (pronounced mess-taw-HAY), is too hard to pronounce as written.

Polis made the remarks to the state’s Geographic Naming Advisory Board, which he created last year to re-name offensive places and landmarks, and urged members to consider an alternate spelling.

“There's a reason why our languages are now going extinct. And it's because of this exact same thing,” said Danielle SeeWalker, co-chair of the Denver American Indian commission. “There's non-Native people in positions of power that are not wanting to use our languages because they can't pronounce them. It's hard to spell it.”

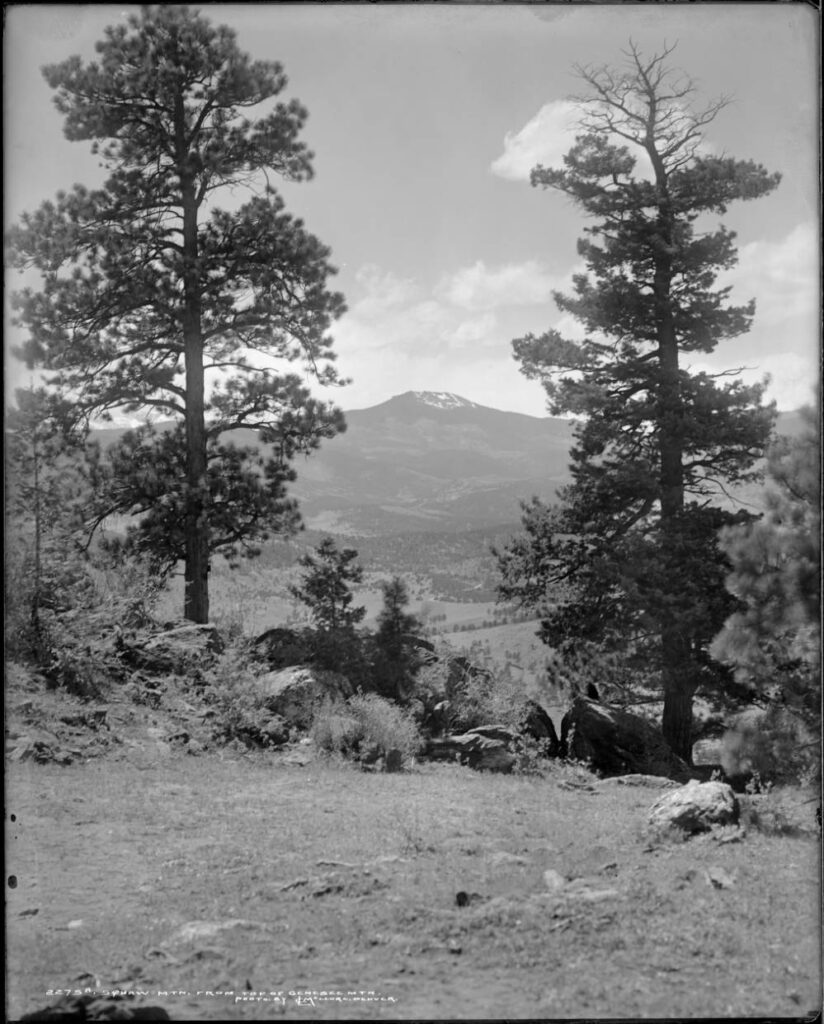

Last month, the commission recommended renaming an 11,459-foot mountain south of Idaho Springs to Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain, in honor of an influential 19th century Cheyenne translator known as Owl Woman. The mountain’s current name is a racial and sexual slur against Indigenous women.

Polis said he would support the new name, but that he initially considered rejecting it.

“It's really not within the realm of comprehension for normal readers that are literate to be able to read the phonetic version that was supplied,” he told the commission, noting the diacritical marks and silent syllable used in the chosen spelling.

“We want to honor Mestaa’ėhehe,” he said. But “I don't think we want people mispronouncing that, or simply just giving up and calling it Squaw Mountain, which I fear is what will happen in this case.”

In recent years, Polis signed a new law to remove American Indian mascots from high schools and he voided the 1864 order to kill Native Americans, which led to the Sand Creek Massacre. But Donna Chrisjohn, an Indigenous education consultant, said his comments about the mountain make clear that there is still work to be done to understand the cultural genocide of North American tribes.

“I think that that a hundred percent speaks to the indoctrination process that every American has been subjected to and that they can't break from it ever. It's there, it exists,” said Donna Chrisjohn, an Indigenous education consultant. “It's hard to unlearn everything that's been taught.”

Democratic state Rep. Adrienne Benavidez serves on the advisory board and told CPR News she thinks Polis showed a narrow perspective on what people can adopt and adapt to. She said the commission has never discussed pronunciation before as it’s weighed new names and she doesn’t think that should factor into its decisions.

While she considers Polis’ concerns well-intentioned, Benavidez said, “people are much more resilient and adaptable than I think the Governor was seeing. I think people have often been to places where the names are difficult to pronounce. There are other states that have much more complicated names than we do.”

Former state lawmaker Joe Salazar is a member-elect of the Democratic National Committee and sponsored the American Indian mascot bill at the capitol. He said the Governor was causing a stir with communities of color for no “logical reason.”

“He doesn't like anything that's difficult apparently, and history be damned and the systemic racism that we feel be damned,” said Salazar, who is Latino with Apache heritage.

Salazar said he thinks the remarks were also a political mistake.

“His colonizer attitude is really starting to become quite grating and he needs to knock it off,” he said, warning that Polis may be alienating Democratic voters ahead of next year’s gubernatorial election.

A spokesman for Polis noted that the governor supports the recommendation but doesn’t want the commission’s work to be in vain.

"The concern is that if Coloradans can’t say or read the names this board chooses, then they will simply continue calling it by its original name, whether that is Squaw Mountain or something else which defeats the purpose of the great work that they are doing."

Republican state Sen. Dennis Hisey represents Clear Creek County at the state Capitol. He said it’s always tough to change any name when it’s been known locally a certain way for years, but that people in the community will likely adapt to the new pronunciation. He’s not sure out-of-state visitors will pick it up as easily.

“I wonder if it gets shortened to some type of nickname and doesn’t bestow the honor on it that this Indian woman deserves. I kind of understand the Governor’s perspective,” Hisey said. “But it’s my understanding that the Cheyenne people put forward this name. If the Cheyenne people are willing to take that risk, so am I.”

And he noted Colorado has plenty of non-English names — “For that matter, tourists can’t pronounce half of our Spanish street names.”

Polis said this peak is thankfully not a geographic location that millions of people refer to, but he urged the commission moving forward to consider pronunciation when recommending names.

“You have a lot of big ones ahead of you. This is just the first, but just keep in mind people's behavior. I think changing ... names in a vault in D.C. is a wonderful thing — we want to remedy the history there — but we also want Coloradans in everyday usage to avoid offensive names.”

Any recommended changes that Polis approves from the state’s Geographic Naming Advisory Board will go to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, which will make a final determination.