On a postcard-perfect day outside a backcountry hut in Colorado’s Sawatch Range, a group of five female veterans stands in a circle, learning Qigong and laughing.

It doesn’t show, but these women were strangers until three days ago. They came together for this long weekend with a common purpose: to share their experiences of military trauma and heal. Now, after three emotional days, these veterans are celebrating the completion of what they call “the curriculum.”

To the uninitiated, Qigong looks like a mix of yoga and interpretive dance. One of the veterans, Amanda Williams, jokingly calls it “Dr. Strange.” But everyone participates with gusto.

The exercise is a welcome break from hours spent inside the Harry Gates Hut, gathered around a small wooden table and surrounded by the history of a different group of veterans: the 10th Mountain Division of World War II. Like the women gathered here today, veterans of the 10th Mountain Division also sought solace in the Colorado backcountry —but fewer soldiers of that generation spoke openly about the trauma they endured.

A place of quiet

The retreat is facilitated by Huts for Vets, a Basalt-based nonprofit that organizes free retreats for veterans using the network of backcountry huts built in honor of the 10th Mountain Division.

Unlike some outdoor-oriented veterans’ programs, the vision behind these retreats has little to do with adventure or adrenaline.

“Up here, you get to disconnect from everything,” says Williams, who served in Iraq as a Navy hospital corpsman and later as an intelligence officer in the Army National Guard. “You’re connecting with one another.”

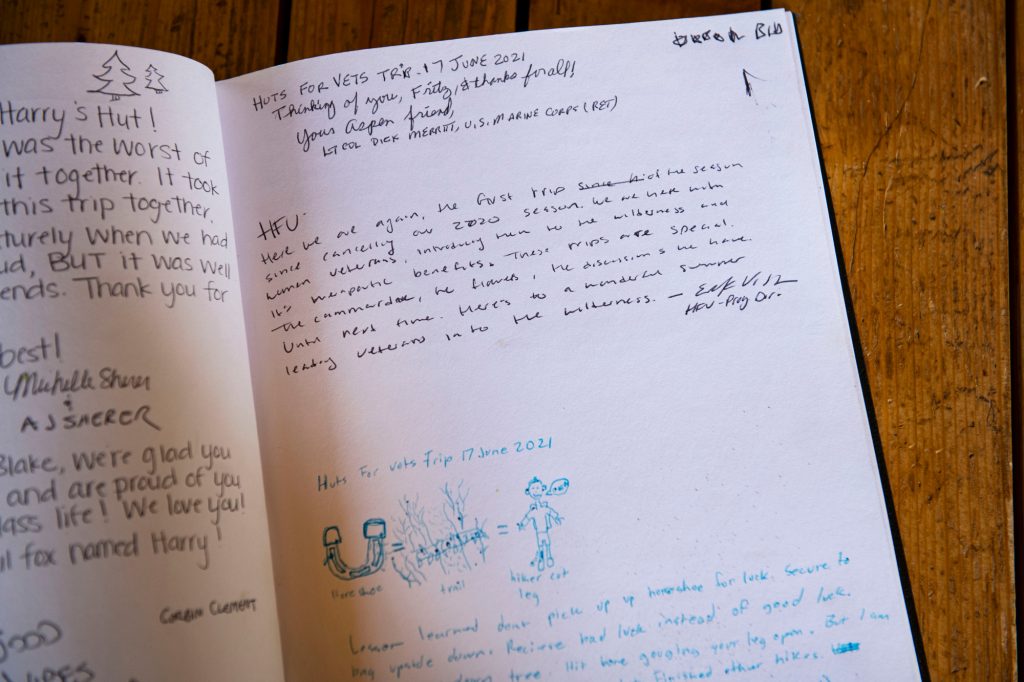

A key vehicle for that connection comes in the form of a hand-bound book given to each participant at the beginning of the retreat.

The books contain an eclectic mix of readings. Essays by American naturalists are interspersed with writings by Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu, Oglala Lakota Chief Luther Standing Bear, and several American war veterans.

In one entry, novelist Cara Hoffman writes, “society may come to understand war differently if people could see it through the eyes of women who’ve experienced both giving birth and taking life.”

Some entries are less literal. “We can live any way we want,” writes Annie Dillard in a short essay entitled, “Living Like Weasels.” “The thing is to stalk your calling in a certain skilled and supple way, to locate the most tender and live spot and plug into that pulse. This is yielding, not fighting.” Huts for Vets’ Executive Director Paul Andersen created the curriculum. In Andersen’s view, the readings are central to the program’s success. “When you marry text with immersion, something positive is going to happen,” he says.

In practice, the curriculum scaffolds the retreat’s central goal: conversations about military trauma. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs estimates that between 11 to 20 percent of recent veterans have post-traumatic stress disorder.

For some of the women on this particular trip, their trauma comes from experiences of combat. For others, it comes from sexual assault or harassment that occurred while they were enlisted, which they refer to as MST — military sexual trauma. The VA reports that 23 percent of women veterans experienced sexual assault while enlisted.

Back at the hut, Williams speaks candidly about her experiences with both sorts of trauma. She returned to civilian life in 2010 and became a firefighter in Minnesota. It’s her military background, she says, that taught her how to act quickly and stay calm in dangerous settings. “I thrive when there’s trauma situations.”

Even so, opening up to non-veterans about her experiences in the military remains difficult. “It's hard to put that in a perspective for someone who's never been there,” she says.

As a facilitator, Andersen’s presence is equal parts understated and magnetic, with wisps of grey hair sticking out from beneath his hat. Andersen is not a veteran — he protested the Vietnam War — but he seems both comfortable and humbled in the company of the participants. “It’s incommunicable,” he says of their time in the military. “Even for me to be in such close proximity with veterans, I only get a glimpse of what their experience is like.”

For his participants, that glimpse is enough. “You can’t pay us to open up to each other, or to ourselves,” says Natalie Solano, who served in the Marine Corps until last year, working as a correctional officer in a military prison. But something about Andersen’s approach — open, nonjudgmental, patient — made Solano feel unexpectedly safe. “The fact that we all open up to Paul, and then he makes us so comfortable opening up to each other? And that changes lives.”

Solano’s transition away from military service coincided with the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We isolate ourselves because it hurts to talk about things,” she says. In her case, the isolation was twofold. Leaving the military, only to enter lockdown at home, was debilitating. This is her second trip with Huts for Vets. “It’s an honor, the hugest honor,” she says. “I’ve been around the block, and this is like, the most valuable thing I’ve ever experienced in my life.”

A hidden history

Beloved by skiers and hikers, the 10th Mountain Division huts have a little known and often romanticized history.

In the years leading up to World War II, American military commanders heard news from Europe of armies suffering brutal defeats in Finland and Albania. The balance of entire wars had tipped because soldiers were unprepared for winter weather.

The United States Army took note. In 1942, the newly-created 10th Mountain Division moved to Camp Hale, near Leadville, to train for combat in the high mountains and extreme cold.

For many months, the troops hiked, skied, and climbed throughout the Sawatch Range in central Colorado. The Trooper Traverse, a harrowing 40-mile ski route from Leadville to Aspen, was first completed in 1944 on a training mission by soldiers carrying 75-pound packs.

The Division’s first troops arrived in Europe just six months before Germany surrendered. They pushed Hitler’s forces north across Italy, but at a significant cost. Of the Division’s 13,000 soldiers, more than 900 died and 3,000 more were wounded.

By the end of the war, the 10th Mountain Division suffered one of the highest casualty rates among all Allied forces.

Many of those same soldiers returned to the mountains of Colorado. At a time when the psychological trauma of war was rarely discussed openly, some former soldiers found comfort by returning to the same mountains they had recently called home.

In the 1980s, a group of these veterans and their families began building huts in memory of their fellow soldiers. The Harry Gates Hut is one of them.

Closing the circle

After a closing discussion, the participants begin packing their bags for the 6-mile walk down the valley. One of the facilitators points me toward a bookshelf.

Memoirs written by veterans of the 10th Mountain Division sit together on a single shelf. Many of their authors were known personally to Andersen.

Relatively few members of the original Division are alive today, but the association they founded continues to manage the huts. They partner closely with Andersen to allow Huts for Vets to run roughly five trips each year at no cost.

For all involved, including the participants, the feeling of continuity energizes the work. Although these huts no longer serve the 10th Mountain Division as they once did, new generations of veterans are taking their place.

After the trip, Andersen looks out over the Roaring Fork Valley. The wildfire smoke that filled the sky the previous night has vanished with the shifting wind. After the last participant leaves for the airport, he reflects on his work and the 10th Mountain Division:

“Bringing veterans to huts that are dedicated to veterans — it completes their mission in a way that I don't think they ever thought that they could.”