Isaac Horton is in high demand.

He’s just 21 years old, but even at 19, he was already burned out at retail jobs like Target and Amazon. Horton is smart and ambitious — and realistic about the cost of a college degree.

“I was unwilling to kind of burden myself with six-digit student debt plus interest for decades versus just being presented an opportunity to actually get the skills I need outright, no tuition costs, nothing, just my time and effort in a couple months,” he said.

He saw an ad for ActivateWork. It offers tuition-free IT training, typically a 15-week boot camp, 12 months of career advising and connections to industry jobs. Courses include desktop support, security fundamentals and software engineering. Companies pay a fee for the service.

Colorado has one of the biggest tech gaps in the nation. There are nearly 25,000 unfilled cybersecurity jobs alone. The jobs make on average six-figure salaries. But there aren't enough people to fill them. Half the jobs don’t require a four-year degree. And banking on the current post-secondary system to produce graduates isn’t enough.

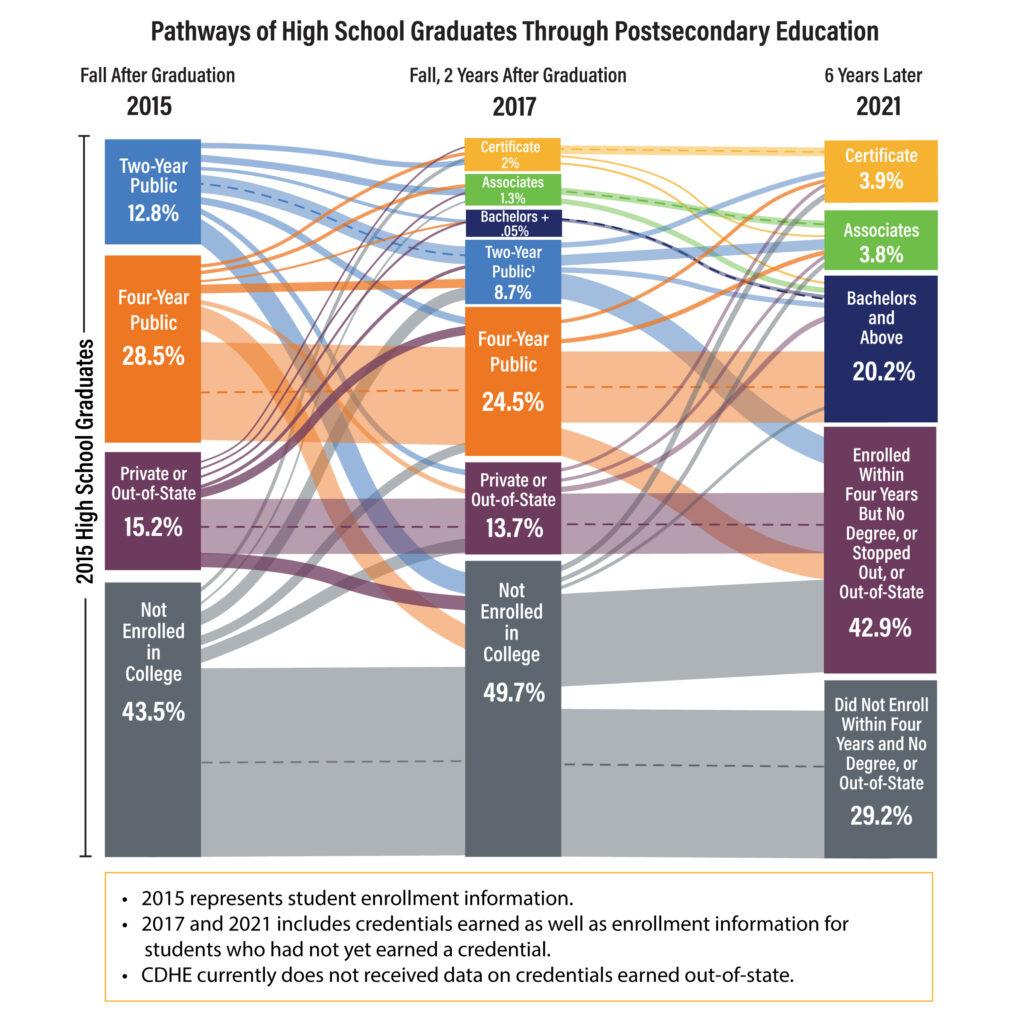

Take Colorado’s high school graduating class of 2015. Six years later, just 28 percent have completed a certificate, associate’s or bachelor’s degree.

Increasingly, companies are looking to organizations like ActivateWork that offer free short-term credentials to learners ages 18 to 55 eager to start careers.

“The demand for talent is off the chart, yet the supply is constricting as higher education gets more expensive,” said ActivateWork’s chief operating officer Kathryn Harris. She sees a huge untapped pool of workers, especially folks in their late 20s, 30s and 40s stuck in jobs that don’t have career paths.

“They've always had an aptitude or an interest or passion in technology, but they haven't had the resources or the time to skill themselves up,” she said.

They’re also more diverse — a plus in a tech world that’s currently very white and very male. ActivateWork screens candidates for work ethic, initiative, follow through, coachability and technical aptitude.

Horton enrolled in the introductory Comp TIA A+ certification course. He’s been a technical support specialist at First Bank for two years making about $45,000 a year.

“That certification alone will open up almost all of Denver in the surrounding cities for a variety of well-playing opportunities,” he said.

Horton has learned, however, for middle-level jobs, like technical support engineers, many companies still require four-year degrees or equivalent experience.

“It’s very picky and the competition cranks up to 11 at that point. Moving up from there, until you can get in, it’s like climbing up a vertical wall.”

ActivateWork sees this huge demand for middle-skill tech jobs like software engineers and network security experts. It’s launched a program that helps companies set up apprenticeship programs based on the precise skills a company needs. Harris recalls an employer who started a cybersecurity apprenticeship and took on several hires, including three ActivateWork graduates.

“They are exceeding the other hires in terms of the number of tickets that they can move through in a given week. And so, all of a sudden, you're starting to say, ‘Huh, I always thought I needed to have a candidate with a four-year degree. I always thought they needed to have these types of experiences.’ ”

As public dollars for higher education have dwindled (Colorado ranks 47th in public investment for higher education) forcing tuition costs up, many argue that earn-while-you-learn model of apprenticeships are a low-cost, quicker pathway to high-skilled, well-paying jobs. Even a final legislative task force report said Colorado isn’t focused enough on post-secondary programs that get learners into well-paying jobs.

Workforce experts and groups like Colorado Equitable Economic Mobility Initiative are advocating for more government support and incentives for organizations like ActivateWork, Climb Hire, and CrossPurpose that provide learners with effective training tuition-free and have a track record of helping them land and keep good-paying jobs in high-growth, high-wage sectors. ActivateWork’s Harris hopes for more incentives for employers — there aren’t enough participating — to test out the apprenticeship strategy.

So far, Colorado has dedicated $200 million from the American Rescue Plan Act to workforce development and education.

Seventy percent of Colorado high school graduates don’t get a certificate, associate’s or bachelor’s degree within six years.

That means there’s no effective plan for the vast majority of Colorado students to get into good-paying jobs. So many workers in their 20s, 30s and 40s have spent years feeling trapped in lower-paying jobs, or jobs they weren’t interested in.

When Felicia Butler, 27, was in high school in Henderson, the focus was all about getting a good score on the ACT and getting into college.

“Other than that, like, welcome to the working class,” she recalls.

She was accepted into college after high school but suddenly became homeless.

“I had no skills or knowledge on how to advocate for myself, how to ask for help, how to problem solve,” she said.

She spent the next nine years doing everything — construction, retail, food and beverage. During the pandemic, Butler was working multiple jobs including overnight shifts at an Amazon warehouse.

“And just being worked, being worked ... I'm working two jobs and it feels like I'm just running in a circle, I was just getting burnt out.”

She saw an ad for Climb Hire. It provides tuition-free training for a number of career tracks: customer experience, salesforce administrator, financial services or Google project management. The mission statement on the website caught her eye.

“To help talent build economic mobility.”

Butler went through the Salesforce training program, which gives people the technical skills to help businesses using the Salesforce platform. She now works as an operations administrator and event planner.

“2021 was the first time I was able to provide myself with stable housing. And that is really where my life changed.”

For many learners, the challenges of completing even a short-term credential program while trying to pay rent and buy food can be overwhelming.

Emeline Peralta was the first in her family to attend college.

“Keyword ‘attend,’” she told a group at a spring roundtable on short-term credential programs attended by Sen. Michael Bennet.

Like so many, she never finished. Peralta did seasonal work in the resort communities for several years. Eventually, she couldn’t afford rent. Peralta discovered Climb Hire. But working in the day and trying to keep on top of her studies and homework even for a short-term credential, with an unstable living situation, she almost quit that.

“I get really emotional thinking about that really dark time where I almost quit. I almost quit because I couldn't afford to do better.”

She was able to move in with her boyfriend and finished the program. She now works as a program operations coordinator at Climb Hire. Peralta has doubled her wage compared to when she worked three jobs.

“The quality of life has improved significantly. It's a weird thing to go from survival mode your entire life. And now I have the privilege to dream bigger ... I’m incredibly happy and proud and confident. I have found a professional identity that I can build on.”

Graduates of short-term credential programs say access to federal aid to help pay expenses would have helped. Currently, students that don’t attend an accredited higher education institution can’t get federal student aid like Pell grants. Sen. Bennet is co-sponsoring a bill that would let learners who attend high-quality trade schools, community colleges, and short-term credential programs with proven outcomes get access to aid.

Another new state law aims to speed up a student’s ability to earn stackable credentials, where credits accumulate as students try to pursue a degree.

Randy Cordova is a perfect example of how the education system loses so many talented people who aren’t able to go directly into a degree program.

“Four-year college ... it didn't even seem like reality to me. It was either you went to college or people dropped out and worked,” said Cordova, 49.

As a boy growing up in Aurora, he remembers being fascinated with early home computers like the Commodore 64. But he said he didn’t do well in school and wasn’t encouraged by counselors.

“I think from the sixth grade on, I got all F’s and D’s. I didn't even pass. I don't even remember much of it. I remember a counselor telling me at one time that I should be a construction worker and construction is an honorable profession, but I think they were kindly telling me that I wasn't smart enough to do anything else.”

For the next few decades, Cordova did a lot of different things — construction, plumbing (he even worked on the plumbing in the downtown ActivateWork offices). But one day he just quit.

“I was unhappy. I always wanted to work with computers and I was just unhappy.”

He’d been taking classes for a computer information systems degree at Metro State University, and near the end of the degree, began going full-time. But that left him with no income. He panicked and started applying for IT jobs but was told he didn’t have the experience. Cordova saw an ad for ActivateWork, took the course and some alumni computer classes. In an entry-level IT position, he was making the same as a construction worker with tenure and now also has better benefits. He now makes $55,000 at Centura Health as a client desktop engineer.

“Now I feel like I’m doing what I was meant to do,” he said.

Cordova did finally get that bachelor’s degree. (Workers with bachelor’s degrees earn 67 percent more than those with just a high school diploma.) It will help with his goal of becoming a network engineer. Once he posted his bachelor’s degree on Linked In, it brought another wave of recruiters desperate for IT talent. But Cordova said he never would have got his foot through the IT door had it not been for the short-term credential program.

“Certifications and experience almost trump education. I look at people in the field — a lot of people don’t have degrees — they have certifications, and they have experience,” he said.