It’s the holiday season, and nothing is worse than having to miss a flight home thanks to catching a nasty bug. And this year, there's a trio of viruses going around that could cause a lot more than a runny nose.

It’s already proven a difficult respiratory virus season for Colorado as COVID-19 cases have risen sharply in recent weeks. There’s also flu and RSV, which have caused an unprecedented number of hospitalizations among children this year.

The typical advice still applies — well-fitted N95 masks, vaccines, avoiding large crowds, and social distancing protects you and others around you. But for many, some of those options are not possible, with return-to-office mandates, and for others, no longer negotiable as COVID fatigue sets in almost three years after the virus was first detected.

Jose-Luis Jimenez, a chemistry professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, believes those worried about sicknesses ruining holiday plans could do one simple thing to reduce risk of infection — thinking about ventilation and airflow as you go about your day.

“The basic concept is, think that everybody you are next to is smoking and imagine that they are exhaling this smoke and you wanna breathe as little of that as possible,” Jimenez said.

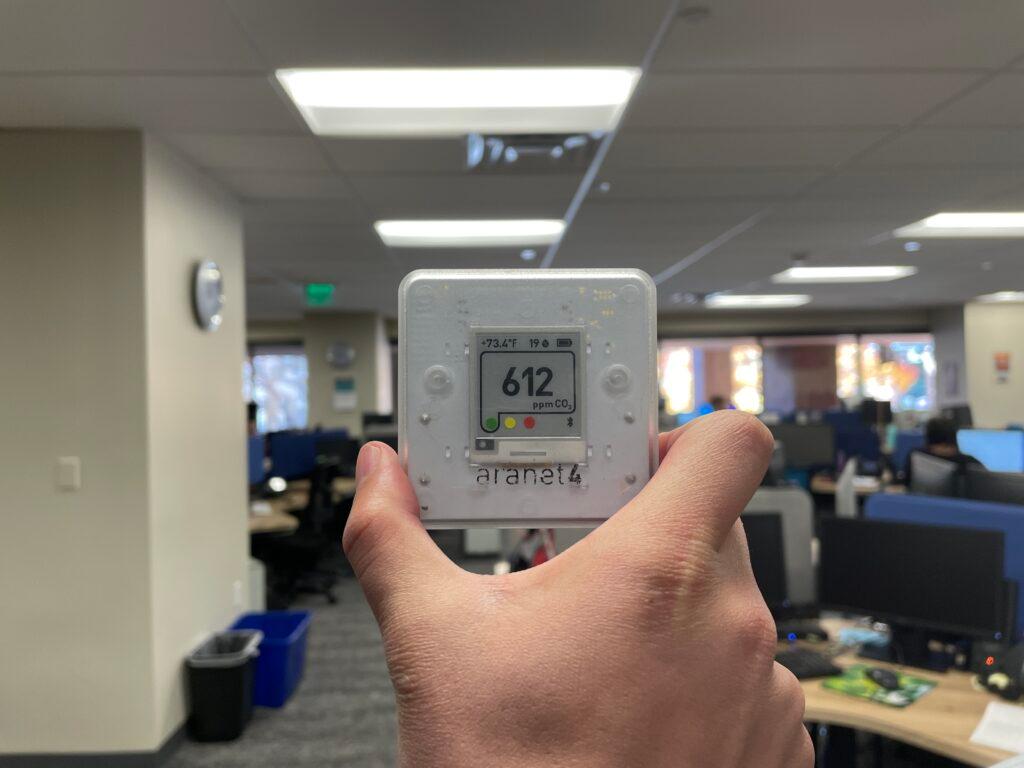

Throughout the pandemic, his constant companion (besides a well-fitted N95 mask) is an ordinary-looking, simple tool: a clear square box, which regularly posts a number in large black font.

He takes a carbon dioxide monitor everywhere — his office at CU, museums, fast food joints, planes, trains, automobiles, along on his travels to his native Spain, and more.

His goal is to promote awareness of aerosols in the transmission of illness, through the monitoring of carbon dioxide in indoor environments. High levels of carbon dioxide means a space is poorly ventilated, and there’s a greater chance of breathing in a virus someone else might be carrying.

The general concept, he said, is summarized by a maxim in the aerosol research world: the solution to pollution is dilution. Jimenez said people are just starting to understand the risk of dirty air as similar to the way humans learned of the dangers of dirty water.

"Society changes much more slowly than advances in technology or in science, you know?" said Jimenez. "This is an inconvenient, scientific truth." He said he hopes the knowledge grows and becomes more widely understood, and soon. "But it's gonna take a while. It is not gonna be done tomorrow.

The monitor usually measures around 400 parts per million (ppm) when outdoors. Well-ventilated spaces are typically under 800. When the monitor goes above 1,000 ppm, that’s typically when Jimenez recommends opening a window or moving outside to avoid stale air.

CPR News reporters took two of these monitors around metro Denver — and beyond — to measure CO2 levels in areas Coloradans might commonly find themselves in during the holiday season.

What's your home like?

If you’re like most Americans, you spend a lot of time at home. And that’s where you’ll be if you’re recovering, possibly still contagious, from a respiratory virus. Maybe you live in a one-bedroom apartment, or a sprawling bungalow with you and your two kids.

The chances are, your building’s air quality might be contingent upon its age. Many commercial buildings and public spaces received upgrades to ventilation systems at the onset of the pandemic; many residential homes did not.

In reporter Paolo Zialcita’s one-bedroom apartment, where he lives with his fiance and his family of plants, CO2 levels fluctuate between 900 to 1,100 ppm.

Opening a sliding glass door or a window vastly improved the air quality, with readings lowering to 600 to 700.

What about offices, airports and retailers — places you’ll need to be at for work or holiday travel plans?

Offices can similarly fluctuate in numbers. At CPR News’ downtown office, which is usually about 25 percent full with some masking, the monitor usually measured between 600 to 800 ppm, depending on what part of the office it was in. That’s among the lowest numbers in public places CPR reporters saw.

But not every office is like that. Jimenez said people should be most aware of air quality while in public places, like offices, classrooms and other shared spaces. Odds are, in areas with a significant number of respiratory illnesses, there’s at least one person in the crowd nursing a sickness, and potentially contagious. The bigger the crowd, the more likely the number of infectious folks.

That remains especially true in public transportation hubs, like train stations and airports. If you have holiday travel plans, these places, and their crowds, are pretty unavoidable.

In his travels, Jimenez said airport bathrooms are often one of the riskiest spaces, with lots of people coming and going (literally) and air quality often not as good as other spots. “The ones I have explored are poorly ventilated,” he said.

Some medical experts view this kind of air quality monitoring as just part of the larger picture of how bugs spread.

Dr. Michelle Barron, an infectious disease expert at UCHealth said CO2 monitoring is a decent proxy for measuring relative air quality. But there are a lot of variables in how someone might pick up COVID-19 or flu or RSV.

“Maybe the air quality is fine but somebody sneezed and just touched a handle that you grab on and then you rub your nose. It's how people get sick pretty commonly,” she said. “So I think it's one piece of this big puzzle.”

“The train, when you go from the main terminal to the departure terminals, that tends to be pretty high, I would say typically is 1,500, something like that,” Jimenez said at Denver International Airport. “[It is] 800 here in the terminal.”

Shopping for holiday presents will also present a bit of a risk. Malls are big, expansive places, and often packed to the brim with shoppers when December comes around. CPR reporter Paolo Zialcita saw levels creep around 1,000 ppm in shared corridors between stores, but also witnessed extremely low levels in large, empty department stores. Those wanting to avoid potential exposure in indoor malls may want to consider going to outdoor outlets or order online.

Grocery stores can fluctuate, depending on the size and number of people inside

Even if you’re not traveling for Thanksgiving or Christmas, there’s one busy holiday destination that’s hard to avoid — groceries.

At a Trader Joe’s in Boulder during peak weekend hours, not many people were wearing masks. The resulting measurement was about 1,400 ppm, over triple the baseline number seen outdoors.

Larger groceries with more aisles and higher ceilings tested better, with readings often below 900.

Health reporter John Daley visited a Denver grocery store right before Halloween. It was moderately full, and in an uncrowded aisle, the number was below 900.

What about restaurants and bars?

Since the start of the pandemic, public health officials have warned people about the high risk associated with going to restaurants and bars. Earlier in the pandemic, these venues were shuttered. But now, they’re back, with zero restrictions and limited outdoor dining due to colder weather and the sunsetting of relaxed pandemic-era regulations.

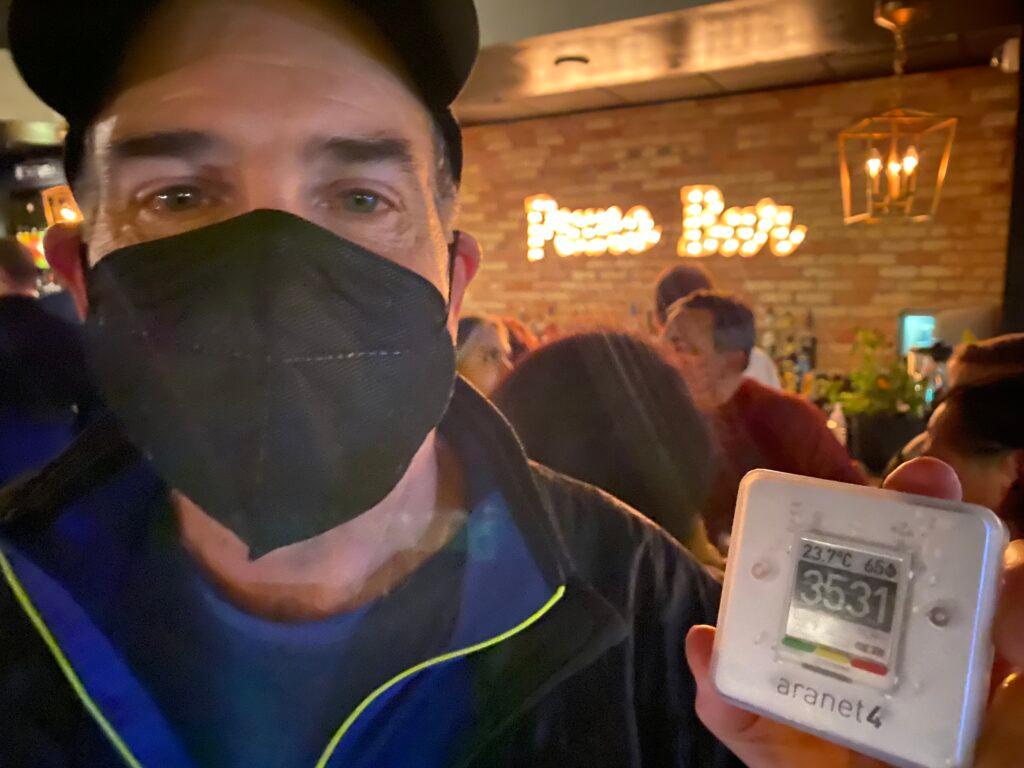

When entering a crowded restaurant off Pearl Street the weekend before Halloween, Jimenez immediately noted a lack of open windows or doors to let air circulate.

“The meter is reading 1,060, which is definitely not great for a place where people are eating and talking without masks,” Jimenez said.

On a recent visit to the college town of Madison, Wisconsin, Daley documented the highest level he’s seen to date. It was more than 3,500. That was in a crowded piano bar inside an older building; windows and doors were not cracked open. As it filled up with college-aged students and mostly 20-somethings, there was barely an N95 mask to be seen.

The number soared as more people entered the bar.

Don’t judge a book by its cover, Jimenez warned, however. Even if a restaurant or bar looks crowded, there may be other factors in play.

“It’s hard to know what they’re doing with the ventilation systems. Sometimes it's always the same,” Jimenez said while in a basement bar in Boulder. “Some ventilation systems, when there are more people, they run them stronger, so it's hard to predict. That's why measuring is a good thing, you know?”

Air quality is part of a ‘vaccine-plus’ approach to ending the global pandemic, say hundreds of scientists

Experts from more than 100 countries described indoor air quality as critical to ending the COVID-19 pandemic as a public health threat, in a study published in the journal Nature. Jimenez was one of the co-authors.

The paper states “current evidence guided the panelists to near-unanimous agreement that SARS-CoV-2 is an airborne virus that presents the highest risk of transmission in indoor areas with poor ventilation.” It said governments should regulate and incentivize preventative measures, like ventilation and air filtration, and high priority should be given to preventing transmission in the workplace, educational institutions and commercial centers.

It called the virus a “persistent and dangerous global health threat,” and urged a “vaccine-plus” approach, which also includes increased masking, testing and treatment. The study included 57 recommendations by 386 multidisciplinary experts from more than 100 countries and territories. The experts carried out what’s called a Delphi study, which challenges experts to find consensus on answers to complex research questions.

“Unfortunately, COVID-19 is not yet over,” Jimenez said, in a press release from CU. “But there are many things we can and should be doing about it here in the U.S. and across the world, and a high priority should be paying attention to and taking action by cleaning our indoor air.”

A push for better indoor air quality at DIA

The crisis has sparked new efforts and reforms aimed at improving indoor air quality, including Japan, Taiwan, South Korea and Belgium, said Jimenez.

Lawmakers in Belgium passed a ventilation plan requiring publicly accessible places, like bars, restaurants, cinemas, theaters and gyms, to monitor air quality and have a visible CO2 monitor. That sensor could not be immediately near a door or window, which would lower readings but not reflect the true levels in a space, according to The Brussels Times.

The push to alert the public about indoor air quality has become a global movement. Jimenez’s dream is to have a CO2 monitor in every building, every plane, every train so people can see for themselves.

Denver International Airport currently monitors CO2 levels at all spaces in the Airport Office Building, the main terminal and concourses, said public information officer Stephanie Figueroa.

And more is to come on that front. Concourse B and new expansions in concourses A and C have a monitoring system “which will automatically trigger fresh air” to be introduced in the HVAC system once the CO2 level exceeds 900-1,000 ppm, she wrote in an email. The main terminal building and concourses A and C will have an automatic system to introduce fresh air as part of upgrades related to its a new environmental performance contract it announced a few weeks ago had begun construction.

DIA is also installing new CO2 sensors all around the airport as part of renovations there and will post readings on thermostats the public can see, she said.

For its part, RTD said it agrees that CO2 monitoring gives an indication of the ventilation capability in a space and that that is an indicator or air quality.

Senior public relations specialist Laurie Huff said the agency’s trains are well ventilated and readings on a CO2 monitor “don’t correspond directly to risk of infection” – it corresponds to the number of people breathing in the space. Several other factors need to be looked at “to understand what is happening to the air inside a bus, plane or train, including but not limited to circulation or movement in the vehicle, filtration, temperature and humidity,” Huff wrote in an email.

On its website, RTD addresses air quality on light rail, commuter rail and buses, as well as the underground bus concourse at Union Station.

On commuter rail lines, like the A-line to DIA, the website states the HVAC system exchanges the air within each rail car “about every four minutes – or 15 times per hour – with the doors closed, an estimate determined by a vehicle engineer.” Additional fresh air is introduced into the passenger compartment each time a commuter rail train stops at a station and the doors open.

Each car includes two HVAC rooftop units that run independently of each other in the event that one fails. With both rooftop units running, 3,800 cubic feet per minute of air is supplied to each car, 29 percent of which is fresh, 71 percent recirculated, according to the site. This air is supplied using overhead ducting and registers that run the length of the car and returned to each unit in the ceiling near the passenger doors on each end.

Bottom line?

"The more people in close proximity, the higher the risk," Huff said. "RTD can lower this risk somewhat with ventilation and filtering, but we will not eliminate it. The amount of risk each person is willing to take is a personal decision."