The three younger sisters of a 1990 murder victim say they will oppose the early release of her killer when she speaks with a member of the Colorado State Board of Parole on Wednesday.

“I understand she wants to get out, but do you understand what you have done or what you’ve taken away?” said Deborah King, 62, an insurance precertification representative at a hospital in Georgia, where she now lives. “It’s been all that time and I understand that, but can you bring my sister back?”

She was three years younger than Beatrice King, who was killed the day after her 33rd birthday, in Aurora. That’s where Beatrice lived after moving away from the family’s home base in Detroit. She would be 65 now.

In December, Gov. Jared Polis offered about two dozen clemency grants, including one to Robin Farris, who murdered Beatrice King in King’s Aurora apartment in February 1990 after the one-time couple had had a quarrel.

Robin Farris was convicted of first-degree felony murder and has served approximately 32 years of her sentence, life without the possibility of parole for 40 years. The governor’s commutation would make her eligible eight years sooner, and anytime after the hearing next week, if granted, she could walk free — with conditions — on parole.

None of Beatrice King’s three younger sisters want to see that happen, and they all plan to attend a virtual meeting that will occur at a time to be determined on Wednesday. They will be able to share their views about why they don’t want Farris to be granted parole, they said.

Farris, 61, was recognized in Polis’ clemency letter as a model prisoner who spent her sentence counseling other women after a 2,000-hour training she completed while incarcerated, and for holding herself accountable for what she did.

She has two pro-bono clemency lawyers who included in their clemency application a video in which former prisoners who knew Farris spoke of how important her emotional support was. In an interview on Thursday for a story that was published Friday, Farris spoke of how much she learned and grew while behind bars, and how filled with regret she is for taking Beatrice King from the family who loved her.

The three sisters said they had been contacted by victim’s rights representatives from Colorado, and made clear that they opposed Farris’s early parole before Polis granted clemency. The governor’s office declined to provide CPR News with the materials Polis relied upon in making his decision to give Farris a chance at parole, saying the documents were protected by law.

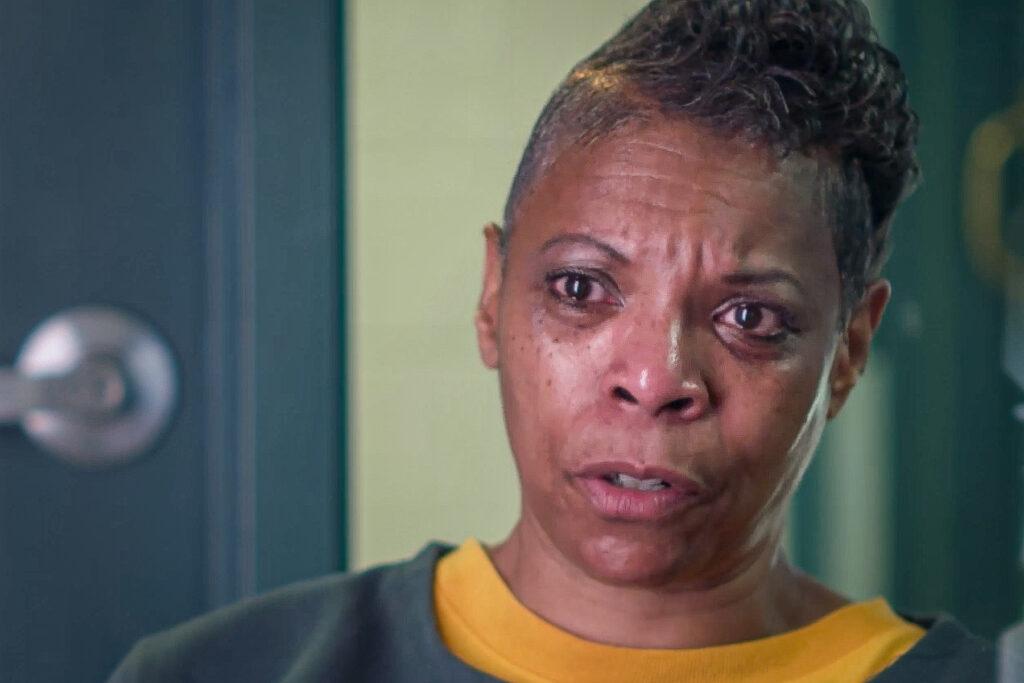

Sylvia Cox, a 59-year-old registered nurse who lives in Detroit, contacted CPR on Friday after she learned about CPR’s coverage of the case. She and her two other sisters – all interviewed by phone – say Beatrice King has never been forgotten; the pain of her loss still lingers; they don’t want to hear apologies or anything else from Farris; and that they’d like her to spend the full 40 years locked up.

Cox, who was emotional during a 30-minute telephone interview on Friday, said that each time she learns that Farris has filed an appeal or a clemency application, she and her sisters rally against it. “Each time that we are notified, we write letters and we do whatever that we possibly can do. Because we are against clemency. We are against parole.”

The parole board member Farris will meet with, according to a document received by Cox, is Daric Harvey. Appointed by Gov. Polis in 2020, Harvey, vice-chair of the board, is the retired Cañon City police chief. After the meeting, which Farris’ clemency lawyers imagine will last 15 minutes, Harvey is expected to report to the nine-member board, which will decide at a later date whether to grant Farris parole.

Marissa King is the youngest of the King sisters, born in 1995, five years after Beatrice King was murdered. A first-year law student at Nashville School of Law and the executive legislative analyst for Tennessee State Representative Torrey Harris, she is now 27. She said that although she never got to meet Beatrice, called “Bea Bea” or “B.B. King,” after the blues singer, she has always been told by her sisters that she reminds them of her.

“Listening to stories about her, ‘You’re very, very, very, similar in personality, in nature,’” she said during a telephone interview Friday afternoon. “And it really made a difference, too, when you know things could be different, and obviously, what a person could have accomplished if they were still here. That is something that Sylvia and Debbie still struggle with. I was kind of able to get through it in a different way . . . I can tell you it’s still an open wound, worse than our parents passing.”

She said requests from Farris, often through intermediaries, for interactions related to restorative justice and offers of apologies, never landed well with the King sisters. Marissa said she understands from her work with victim’s families in Tennessee, that clemency has to do with establishing a relationship with loved ones of the victim.

“And that hasn’t happened at all,” she said. “It was never a chance to sit down and have a conversation. It was, ‘Let us tell you how you should feel about what is going on right now.’”

The three sisters also agree that in the process of focusing on Robin Farris and her clemency efforts, the life of Beatrice King has been left in the shadows.

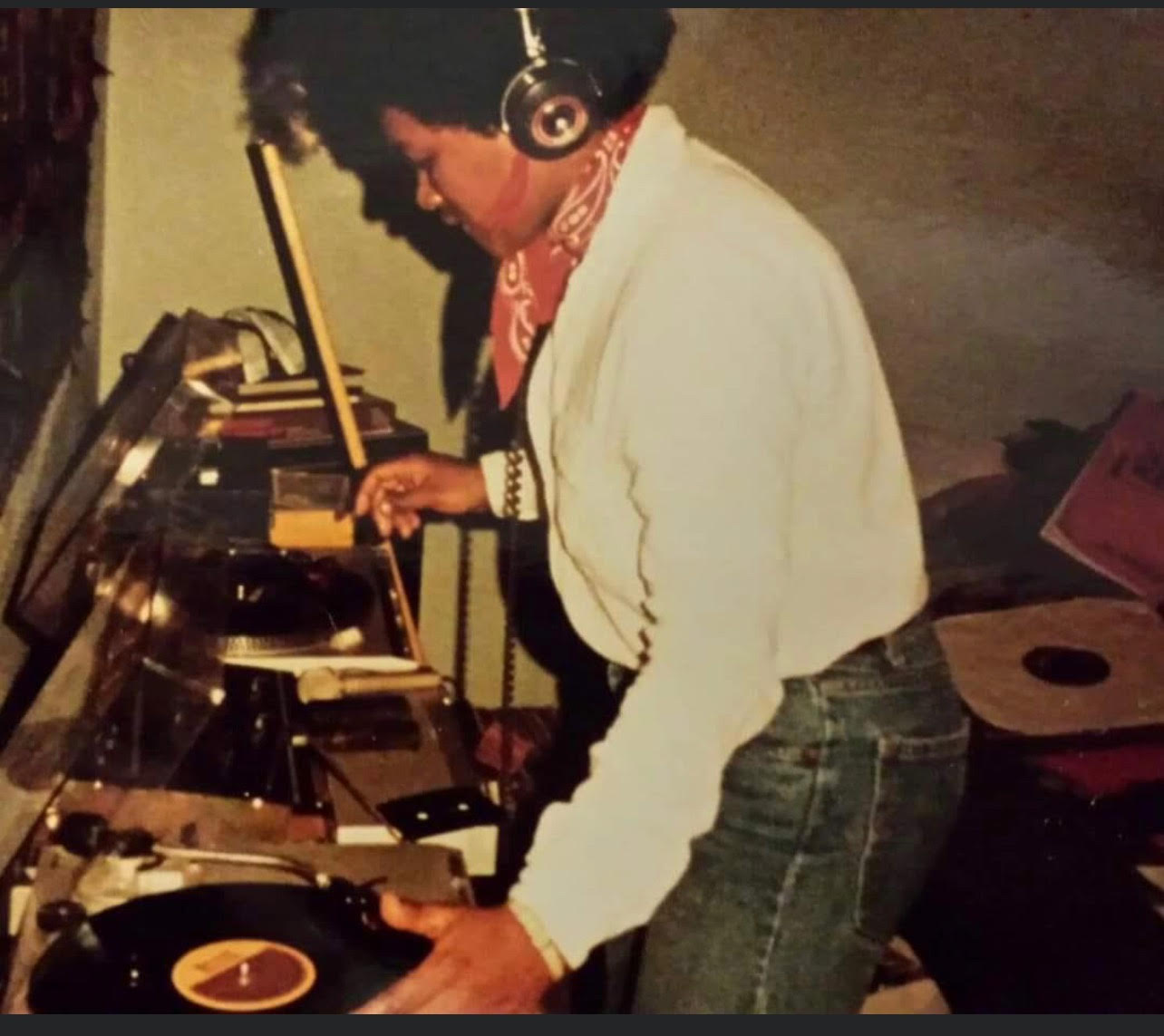

According to Deborah King and Sylvia Cox, King graduated from a high school in Detroit in 1975. She loved being outdoors, doing landscaping, arranging flowers, playing with children, helping other people, and being there for her sisters.

“She was my biggest fan,” said Cox. “A true big sister…She was always there. She never missed a moment. My first apartment after [college], she helped me move in.”

Deborah King has a similar memory of support from her big sister when she went into labor with her daughter five and a half months into her pregnancy. “I told her I was in labor; she dropped whatever she had to do and she was right there.”

When asked if the amount of time she has served already was acceptable, Cox said, “No I do not.” When asked why, she said: “She took a life. She should have life.” She added that before their father died, he asked her to try to make sure Farris served the full 40 years.

She said it’s a no-go for any kind of talks or forgiveness.

“The family is dealing with what you did. You have to deal with that yourself,” Cox said. “You’re trying to contact us to make you feel better. That’s not gonna work. We’re having to grieve. We’re still grieving.”

Farris’ two lawyers, Kristen Nelson and Risa Wolf-Smith, have said that while they understand the family’s pain, Farris has changed since she began her incarceration. They feel she has earned this shot at redemption and freedom, based on the person she is now, not what she did in the past.

“I think it’s important to talk about excessive sentences like life sentences,” Nelson said. “I think life sentences are death-in-prison sentences.”

Farris’ potential release will give her a chance to show that she has changed, and to reach her potential, after having paid her debt to society for three decades, said Wolf-Smith.

“30 years is a long time and it’s actually coming up on 32 years, and she’s suffered and she’s paid a huge price,” Wolf-Smith said. Of the parole board, she said, “I just would hope that they would be open enough to understanding that she has paid a price.”

The two sisters painted a picture of Beatrice’s life up until the time of her death: she had served in the U.S. Army, stationed in Germany and the Seattle area. After an honorable discharge, she attended Spelman College in Atlanta for a while, but did not graduate. Then, for reasons they’re not fully sure of, she decided to give the Denver area a try. She found an apartment in Aurora, got a job in security, and got into a romantic relationship with Robin Farris, whose daughter she sometimes babysat.

They both recalled that about a month or two before King was murdered, Bea Bea called her sisters to introduce Robin by phone. Her sisters, accepting of King as bisexual, recalled being happy to chat with her.

“We sat down with my dad, and Bea’s on the phone,” Cox said. “She put [Robin] on the phone and she said hi to everybody. And my sister was so excited because she says, ‘She has a young child and I babysit her baby a lot,’ and, ‘This is Robin’ and, ‘Nice to meet you. Hopefully, we can meet you one day.’ Didn’t think she would kill her.”

At her funeral back home in Detroit, they said, hundreds of people came out for the viewing, waiting in lines as long as a full block. Members of the U.S. Army showed up and gave Beatrice King’s father a US flag, which Sylvia Cox now has.

Cox plans to fight the parole effort despite battling Stage 2 breast cancer herself. She believes Beatrice would appreciate her willingness to battle.

“I know she would say to me, ‘You are strong’ . . . Every time I take chemo and every time I get weak, I think about her,” Cox said. “And I don’t think my time is yet ready. I think God has so much more for me to do on this Earth. And that includes being the cheerleader for my sister, cause she’s not able to speak.”