Blind people have been politicians and business professionals, artisans and community activists throughout Colorado’s history, but their stories have gone largely untold.

Historian Peggy Chong wants to change that. Chong is known as the “Blind History Lady” for her research into the personalities and challenges of visually impaired communities in Colorado and elsewhere. She recently won a grant from the National Federation of the Blind to continue those efforts.

Chong said many blind people lose their sight after they become adults. They struggle with how to adapt and neither they, nor the counselors who are paid to help them, have role models to serve as examples.

“(Blind people) are studied for our medical conditions always, but we're rarely studied for what we have accomplished,” she said.

Chong spoke to Colorado Matters host Chandra Thomas Whitfield about the history of legislation and access in Colorado for visually impaired communities, and prominent blind people in the state’s history — including a governor.

Read the interview

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

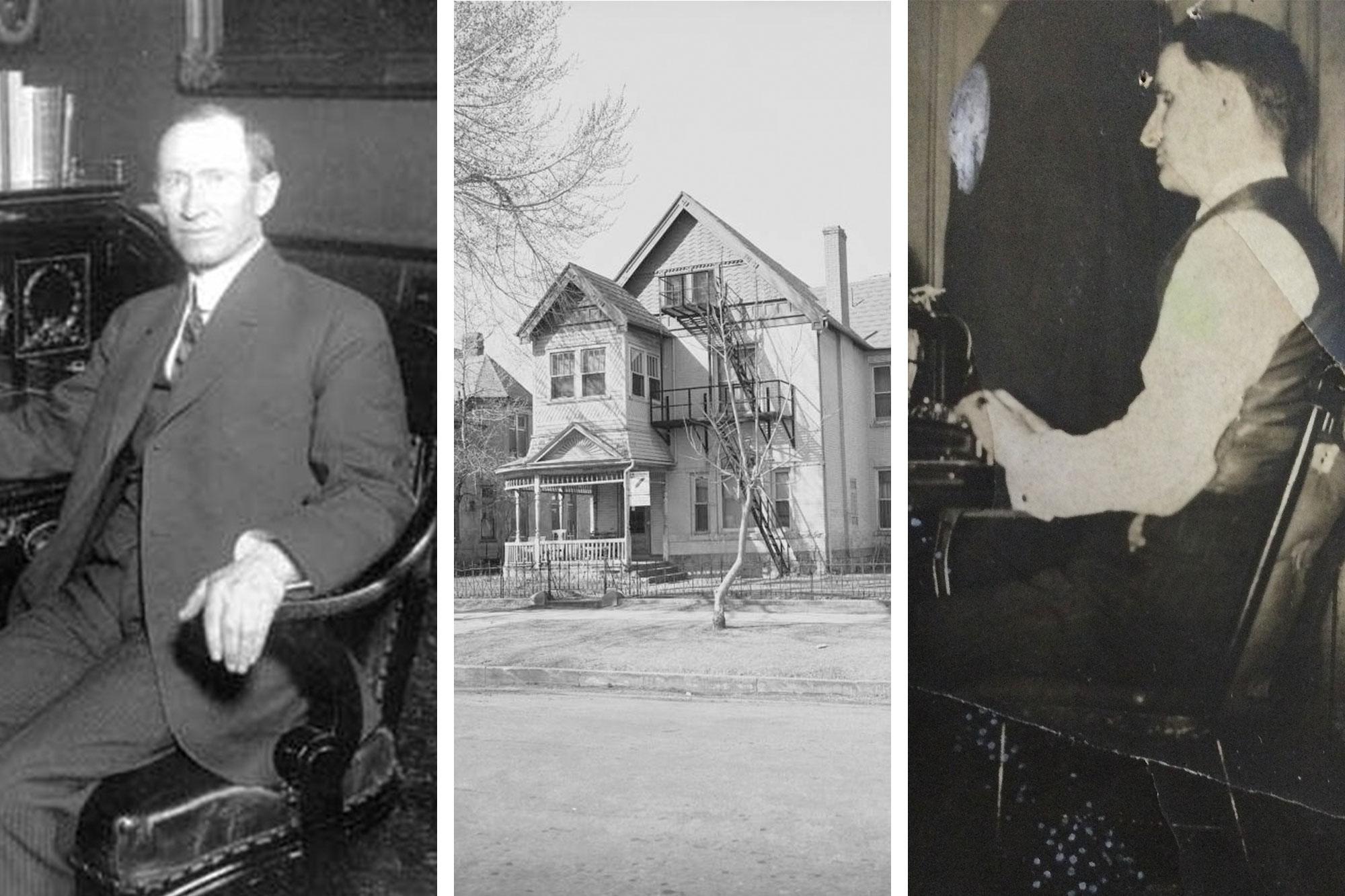

Chandra Thomas Whitfield: I understand one of Colorado's governors was actually legally blind, and that would be Elias Ammons who served from 1913 to 1915.

Peggy Chong: That is correct. He contracted measles when he was a teenager and when he recovered, one of the side effects from the measles was that his vision was becoming less and less. He wanted to be a newspaperman, but did not think that with his vision loss he would be able to do that, so he went into ranching instead.

On his ranch he was confronted with several issues that ranchers were dealing with, railroads coming through, cattle rustling, and all sorts of things. He was really good at getting up at meetings and speaking about what he thought was important for the ranchers, addressing it with the current state legislators and so on, so his community elected him to be a state representative. Then he became a state senator and then, in 1913, he was elected governor of the State of Colorado.

How do you think his vision problems might have influenced some of the causes he took on and some of the things he accomplished?

It wasn't until the last part of his life that he actually addressed vision issues and that was probably because he did not know a lot of blind people at that time.

When he became governor, that's when he really started to know of other blind persons. A man named James Downing was elected to the state House of Representatives in 1916. The two of them also met Lute Wilcox, who was a blind man who ran his own magazine, Field and Farm. He had a printing company, a public relations company, and they got together and started talking about the needs of the blind adults, those going blind later in life, who wanted to learn how to get back out into the job world (and) needed additional techniques, (such as) learning how to read and write in an alternative format.

And so it was when (Ammons) joined up with other folks that he started to work on crafting state legislation that ultimately passed in 1918 that created a commission for the blind, created benefits that were across the board, the same for blind people. So, it wasn't until later on. Most of his focus for many years was on equal rights for women. His sister was very active in women's movements and he took a lot of energy from her in that regard.

Another person you've learned a lot about is Jennie Coward Jackson. She was instrumental in getting jobs for blind people in Colorado in the early 1900s. How did that come about?

She was kind of a spitfire. She had gone to the School for the Blind in Kansas and when she moved to Colorado about 1903 she found basically a wasteland of services for blind people. There was nothing, so she started to seek out other blind people.

They began working on legislation to start a workshop for the blind. It took a few years but Colorado Industries for the Blind finally became a reality. She began teaching there. The people coming to Colorado Industries for the Blind had no skills at all. They were people being abandoned by their family or in poor houses. With her efforts demonstrating that she could teach, that she could get people ready for work outside of a workshop, she became the first traveling teacher for blind people in the state.

She spent her wages on travel because she didn't have a travel budget. She spent her wages on purchasing slates and styluses, which is the equivalent of a pencil and paper for blind people. She started Braille classes, she started weaving classes. Every one of her classes, she had them learn to read and write in New York Point. There were no reading materials so they would write up an essay or a short story and they would pass it to the next one to correct it, but also to reinforce their reading. And they accumulated, if you will, their own little libraries in these reading groups.

Wow. So you've done this research for many years and even picked up the nickname, the Blind History Lady. Why do you think it's important to tell these stories?

I grew up in the blind community. I had a mother who was legally blind as well, and I have sisters who are blind as well. I knew the old rug weavers and the piano tuners and the door-to-door salesmen and I felt sort of ashamed of them when I was a teenager because they were doing these low-level, low-paid jobs, and as a teenager in the blind community I was beginning to meet blind lawyers and blind teachers and blind businessmen. And I did not understand why they were just taking these low-level jobs, but these were blind people that were supporting their families, raising children and sending them to college. They were groundbreaking at the time.

When I was in my late 20s, I was given a job to clean out the files at the Home for the Blind in Minnesota. It was closing. There were file cabinets and boxes of old records and letters and newsletters and all kinds of things. While I was going through those files, I learned of our blind senator. I didn't know there was a blind senator from Minnesota. And that's what got me started. And once I learned how to do family genealogy, my research really expanded with what I now call our blind ancestors.

So it sounds like a lot of this for you was to inspire others who are visually impaired, but also to raise awareness for those outside of the community about the many contributions that those who are blind have contributed to our society.

Absolutely. When a person goes blind later in life – and most people go blind in their working years – they think they're the only one who's ever been a blind banker or a blind judge or a blind business owner, and that is so not the case.

When they go to many of the counselors, social workers, rehabilitation professionals, they are told, ‘Geez, I don't think a blind person's ever done that. Here, why don't you go into vending?’ Not that there's anything wrong with becoming an operator of a vending stand but if you’d really like to be a banker, why don't you go to banking? And there have been blind bankers in this country.

The reason those rehab professionals don't tell you that is because they don't know. It's not taught in their college courses. (Blind people) are studied for our medical conditions always but we're rarely studied for what we have accomplished. To know our history it is important to have role models.

You talked about being ashamed, having your mother being visually impaired. Can you tell us a little bit about depression and those feelings of embarrassment and anxiety in the community?

I want to be like everybody else. I want to be the same as my next-door neighbor. I don't want to be considered the blind lady down the block. I didn't want to be considered the blind mother when I had my child. I wanted to be considered my daughter's mother. I wanted to be considered as the person who showed up and worked for the Parent Teacher Association. I wanted to be considered a valuable part of my community.

Because we don't have role models and we don't have people to teach us some of these cute little skills that help you to mix or help you to get into a sighted crowd, it's really hard and it's difficult to feel like you're wanted.

I had a blind man who told me one time ... I was telling him how I was having difficulty navigating the PTA meeting. And he said, ‘Well, what I do is I get a cup of coffee and I start walking around and people start talking to you right away because they don't want you to spill that cup of coffee on them. So they start talking to you and wanting to have you find a chair. And that's when you say, 'Oh, that's okay. I don't mind standing – and who are you?' And it really did help, just that little icebreaker.

Yeah, and I think this is important because I think sometimes just in any community, you sometimes forget about things like people who may be the only or the first in a situation, someone who is different. And thank you for putting that on the radar for us.

So you recently won the Bolotin Award from the National Federation of the Blind. It's a $5,000 award that goes to individuals who are considered a positive force in the lives of blind people. What will that award allow you to do?

I'm excited. I have found a Harmon Foundation project in the Library of Congress files that awarded blind people a financial award. I don't know a lot about this award, but it was from 1928 to 1932. What was interesting to me about this foundation is that it primarily focused on promoting Black artists, and why did they switch to blind folks? Many of those people whose names I recognize in the list of people they considered for the awards were white. So, I have all these questions.

I'm hoping to find in these files, biographies, the careers that some of these folks had, maybe even some photographs, and tell those stories because these people were not the Helen Kellers or the Stevie Wonders, or Ray Charles. These were broom makers. These were people who made a living selling rugs, who taught piano to the neighborhood kids. So, what was the criteria? I don't know, and I'm very excited to find out.

Wow. It sounds like you have a lot of work to do, but we'll have to hear what you come up with.

I'd love to share.

Historians have to trek through lots of records, and you are legally blind yourself. How have you navigated this work?

Everything is not on the web. A lot of it is in boxes, in basements, and is being forgotten. Like the records that we had here in Colorado, they were in handwritten form. Some of them were moldy, some of them the ink had bled. Some of them were faded, water damaged. What we did with those records, because I couldn't read most of that stuff, we digitized all of those records, so we created a digital file. But that does not mean that they're accessible. We had each of those records scanned with optical character recognition and even the old files that were typed, the files do not allow you to grab hold of that text because it's in an old font, not recognized by the optical character recognition.

So, thanks to COVID, we were able to recruit more than a hundred volunteers who took an enormous amount of time and re-entered all of those into a Word or text file so that a screen reader or a Braille translation program could access the actual text and convert it into either audio or Braille output. So, that's one way of doing it.

I make a lot of phone calls and I sometimes have to make a few donations to genealogical societies or museums to go out and do some little legwork for me and send me back a file or two.

It sounds like what you did is created access, which was the keyword there. It's creating more access to people, yourself included.

And those files are now accessible to anybody, even if you don't live in the United States, as we are putting them up on the Colorado Virtual Library that can be accessed from their website.

Historically, how would you say Colorado has ranked compared to other states in terms of the rights and the services available to blind people?

Kind of depends on the timeframe or what issue you're focusing on. We had a school for the blind earlier than some states. However, we didn't have any adult services of any consequence really until about the 1940s. Blind people were organized here in Colorado, met and shared ideas, acted as their own social services and their own agency, but had limited resources to do that.

The blind people who were from other parts of the country brought into that collective the names, addresses of other blind people from out of state that they could call on and say, ‘Hey, tell me about that law that you guys just got passed.’ That's how our first white cane law got passed, is because we borrowed that from California.

What is a white cane law?

The white cane law allows a blind person to travel independently without the fear of being told, if an accident happens, ‘you shouldn't have been out there anyway.’ It says to the driver that when you see a white cane, you're supposed to slow down and yield. It provides protection that if you're hit by a car that you still do have the right, if that person was impaired as a driver or driving recklessly, that you still have the right to sue that person or have charges brought against them. Rather than saying, ‘Well, the blind person shouldn't have been out in the road anyway,’ which still happens from time to time.

What are a couple of needs for the blind community now here in Colorado?

Transportation is always a big issue. We have a really large issue in the metropolitan area but also getting to other parts of the state. It's very difficult to get to the Western Slope if you're a blind person and you do not have a car. I think we still need to have a lot of education amongst the blind community, amongst employers, amongst legislators, that blind people are capable of doing every job out there, just about every job. And that we should be given a chance. That we should not be just passed on because we're a blind person, because you don't think you could as a blind person. It matters that we think we can as a blind person. And we should be given the chance to demonstrate whether we can or cannot do the job.