An average of three people every business day have signed up for the Colorado Division of Motor Vehicles’ invisible disability identifier logo program since it began last year.

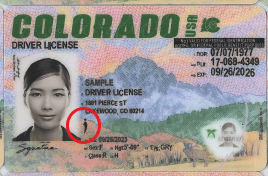

In July 2022, the motor vehicles division began offering motorists with invisible disabilities the opportunity to indicate they have one on their driver's license. It appears, perhaps to some, as the profile of a person with a small head on top, near the photograph. The DMV’s website, however, describes the logo differently: “The “i” symbol from the Invisible Disabilities Association is the symbol that will be printed on the driver's license or ID card,” the website states.

Since then, nearly 1,100 people have signed up.

“From July 1, 2022 to December 1, 2023, 1,096 credentials have been issued with the disability symbol,” said Jennifer Giambi, DMV communications manager, in an email.

That means that since the program began a year and a half ago, an average of three people have signed up every business day.

Colorado is the second state to offer the option, after Alaska, according to the Invisible Disabilities Association.

“Alaska is the first state to pass this much-needed legislation, followed by Colorado,” the association’s website states. “IDA is currently working with legislators across the nation to advance this initiative.”

An invisible disability, as defined by the association, “is a physical, mental or neurological condition that is not visible from the outside, yet can limit or challenge a person’s movements, senses, or activities.”

The association’s definition goes on to state: “. . .the very fact that these symptoms are invisible can lead to misunderstandings, false perceptions, and judgments.”

Colorado’s program aims to interrupt a specific kind of misunderstanding: one with a member of law enforcement. When asked what disability a person can register, Giambi replied in an email: “Any disability that would interfere with a person's ability to communicate with a law enforcement [officer].”

The symbol is the same regardless of the disability, according to Giambi, who stated: “We do not require that a person disclose the nature of their disability.”

To get the disability identifier symbol, a person would need to take a preliminary step before showing up at a DMV office: Coloradans need to have their health care provider fill out a page-and-a-half-long application – Colorado Driver License/Instruction Permit/Identification Card Application for Disability Identifier Symbol.

The form asks for people to fill out their name and address and sign a statement that reads: “I have a disability as defined in the federal "Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990" . . . and the disability interferes with my ability to effectively communicate with a peace officer. I request that the Department of Revenue issue a driver's license, identification card, or identification document bearing a disability identifier symbol. I hereby authorize a Professional . . . to submit information to the Colorado Department of Revenue - Division of Motor Vehicles (DMV) relating to my disability…” It also states the DMV will keep the information confidential.

The form also has a portion for the health care provider to sign, which states that the person has a disability defined by the ADA of 1990 that interferes with the person’s ability to effectively communicate with a peace officer. The health care practitioner signs above a statement that says they’re either a doctor or a licensed provider.

The new identifiers were mandated under a 2021 law sponsored by Dafna Michaelson Jenet, a Democrat representing Commerce City.