On Jan. 31, 2024, Denverite, CPR and KRCC began moving away from using "migrants" when referring to the group of recent arrivals and those who may yet be on the way. Instead, we will refer to the people arriving in Denver and Colorado from the border as new immigrants. Read more about our decision here.

One night in December, Denver Friends Church came to consensus: The congregation would host an emergency shelter for new immigrants, inviting in men, women and children they’d met on the streets of northwest Denver.

As the congregants stood in agreement that evening, Pastor Keith Reeser felt empowered — and overwhelmed.

“It was a beautiful moment. It was also a moment when reality sets in,” he said. “To be blunt, I didn’t know what in the world I was going to do.”

But he soon learned that the city of Denver had answers. Dozens of city employees met with Reeser and inspected the church within just three days, and they later delivered dozens of mattresses. Private donors soon kicked in tens of thousands of dollars. Now, the Denver Friends Church is hosting up to 29 men, women and children each night, and feeding them two meals daily.

“This is a move of God,” Reeser said of the city’s logistical help. “It was so amazing to see so much kindness, so much strong effort … to help this little guy out with an amazing project. They made it so much better.”

The church has joined a sprawling effort that has helped nearly 40,000 people in the capital city. But that humanitarian response has largely ended at Denver’s city limits. And as the costs have mounted into the tens of millions, political tensions have grown. Denver’s elected officials and nonprofits say they are increasingly frustrated by a perceived lack of support from neighboring suburbs, other large cities, and the state government itself — especially Gov. Jared Polis.

“At the end of the day, we need help,” said Councilwoman Amanda Sawyer.

In a series of interviews, several of Denver’s elected leaders said the governor must do more to encourage cities, churches and others across the state to help. Because he has not led a full-throated statewide response to the humanitarian crisis, some said, Polis has left Denver to shoulder an unfair load.

“The governor's stance that this is a Denver problem is untrue, and it is harming people,” Sawyer continued. “There are people across the state, cities across the state, that need the support.”

Councilwoman Jamie Torres acknowledged the governor’s administration has provided much-needed financial and logistical support for Denver — but she’s frustrated Polis has not used his position as the state’s leader to elevate the issue more.

“If this were any other person, I think I might accept that,” Torres said. But “this is a governor who I think has historically been … not just friendly, but welcoming to immigrants, to English language learners. I guess I expected more."

State Sen. Julie Gonzales of Denver said much the same — calling on Polis to respond more forcefully as Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas and other state leaders bus immigrants to Denver.

“The governor has been an ally in the past, but it's really surprising that he hasn't been as strong in [his] allyship as he has been in the past,” she said.

Meanwhile, conservatives and others are pressuring Polis to move in the opposite direction. They blame Denver for accommodating immigrants with supportive policies and by limiting immigration enforcement. They argue that the governor should instead be pushing for laws to discourage new immigrants from coming here.

Now, the situation has reached a fever pitch.

In Denver, Mayor Mike Johnston has slashed city services to find money to keep shelters open and provide other support for people arriving from Venezuela and other countries.

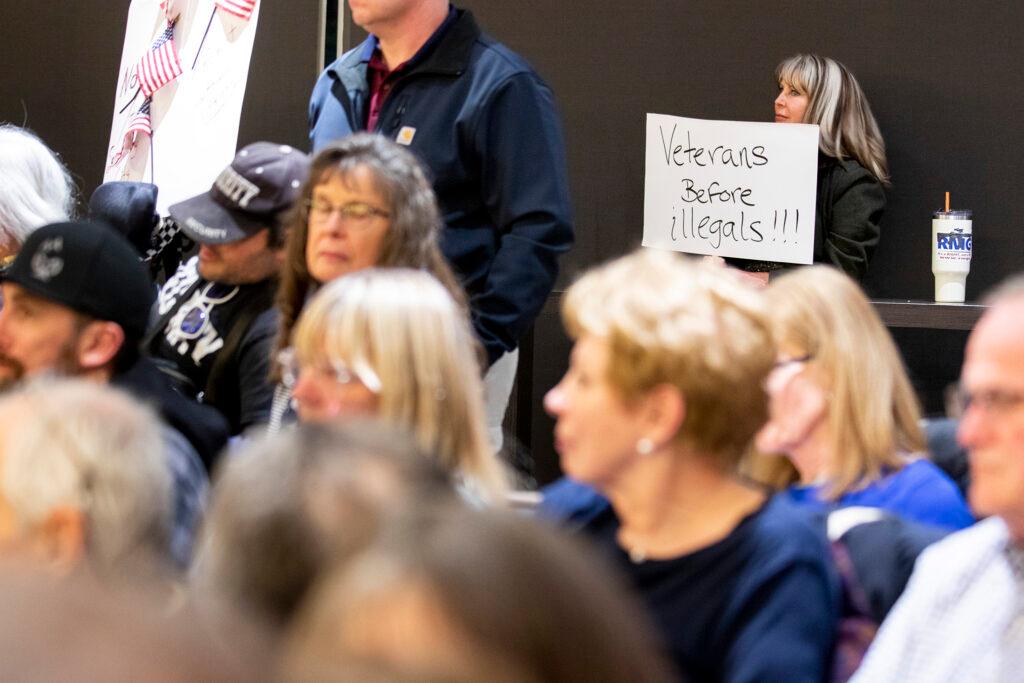

But as Denver strains, the idea of hosting immigrants has drawn strong public opposition in places like Lakewood, El Paso County, Douglas County, including meetings with hundreds of angry people. They’ve been driven both by concerns about the cost of immigrant services, as well as xenophobic fears that immigrants will dilute American culture or even sway the vote, despite the long road to citizenship.

In the middle of it all is Gov. Polis and his state administration.

Polis has talked a lot about immigration recently, including on national television. His main point: Immigration is an issue for Congress to solve — not the states.

"The Governor shares the frustration being expressed at all levels, but the frustration should be directed toward the only government body that can secure the border, enact immigration reform, and provide resources to the communities across the country on the ground: Congress," wrote spokesperson Shelby Wieman in an email, pointing to the governor's years of advocacy on immigration.

But change from Congress has been a long time coming, with the latest immigration reform proposal dying amid Republican resistance.

In the meantime, Polis "remains committed to doing what we can to support local communities and nonprofits who are on the frontline caring for new arrivals," Wieman continued.

The state has provided nearly $30 million of state and federal money, to Denver communities that are helping immigrants, and the governor supports plans to help schools get funding for immigrant children. The state also has helped to coordinate different immigrant support efforts.

That involvement has earned the appreciation of Denver Mayor Mike Johnston. “Mayor Johnston has been in regular communication with Governor Polis about this crisis, and the governor has been a good partner for the city,” wrote spokesperson Jordan Fuja.

But critics say the governor has kept too low of a profile. He did not mention migration in his State of the State address, later explaining that the address was focused on statewide issues — to the chagrin of some Denver council members. And while U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper recently met with Mayor Johnston and a group of new immigrants, Polis has not done similar events.

CPR reached out to the leaders of two different state agencies, the Office of New Americans and the Colorado Division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management Services, for interviews about the state response, but was instead directed to the governor’s office. The governor’s office also declined an interview.

The governor’s office said that each city would individually decide how to respond to immigration, and the state would follow their leads.

"It is natural that different cities have different goals and the Governor wants the state to be a good partner for all of them, including supporting different plans to reduce homelessness, improve public safety, or support new arrivals," Wieman wrote.

That stance has drawn frustration from advocates like Jennifer Piper of the American Friends Service Committee, who said the governor should be pounding the pavement to rally more cities to help.

“I feel like Governor Polis has contributed to this idea that this is just a Denver problem and that's unfortunate,” Piper said.

"I think there are localities who would step into this more if it was clear that they would receive some support … I do think there are some things that the state government could have done to encourage and support local government."

In an interview last month with Colorado Matters, Polis said the federal government, as opposed to the state, is the one falling short.

“There's a much bigger role for coordination. And the big piece that's missing is the federal coordination piece,” he said when host Ryan Warner pressed him on the need for more coordinated state action.

Critics to the governor’s left say that while the state has no power over immigration law, it can still do more to help new arrivals support themselves.

Advocates have floated ideas like offering provisional drivers’ licenses, or even having the state government try to skirt around work permit problems by directly hiring new immigrants.

Colorado’s subtler approach differs from other states that have seen the largest number of arrivals. In New York, Gov. Kathy Hochul went so far as mobilizing hundreds of National Guard members to help manage the needs of tens of thousands of new immigrants. And Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey declared a state of emergency and has dedicated nearly a half-billion dollars a year for new immigrant support.

Colorado’s strategy of quiet, voluntary support

Polis may be trying to avoid the increasingly heated debate over immigration in Colorado, suggested Councilwoman Sawyer.

“I worry that part of that has to do with this political football, this fiction, that Denver is a sanctuary city,” she said.

Meanwhile, conservatives want Polis to move in the opposite direction. They say he should send a message that Colorado is not supportive of new immigrants. They blame Democrats for passing reforms that make it easier for people without permanent legal status to live in Colorado, such as granting non-citizen driver’s licenses and restricting local law enforcement's interactions with ICE.

"This is impacting our entire state. The cities that butt up next to Denver, they are kind of getting pulled into Denver's public policy on this,” said Ramey Johnson, a former Republican lawmaker who has helped to organize anti-immigration protests.

“Denver is a sanctuary city, and now they're asking other municipalities ... to help them,” she added.

Those kinds of concerns have drawn hundreds of people to intense town-hall meetings and led several local governments to declare that they won’t welcome new immigrants.

While the Polis administration has steered clear of those public debates, it appears to be tracking them closely. The state government is sharing intelligence with nonprofits about which communities are friendly and which are potentially hostile to new immigrants, one nonprofit leader said.

“They have meetings with us, advising us of what they hear — for example, ‘Let’s just stay away from taking people to this [particular] shelter in this [particular] city,” said Yoli Casas, of Vive Wellness. She said the administration had the right idea.

“Why would we want to send people where they might be mistreated?” she asked. Casas also praised the state for providing millions of dollars to provide emergency support and daycare for immigrant children

Still, others contend that the state should try harder to get cities involved.

“This is a place where I think that Gov. Polis could do much more to encourage local governments to take a greater part in living our values as a state. I think that we do our best work when we work together and Denver can't do this work of supporting migrants on its own,” Gonzales said.

Denver is not the only municipality struggling with immigration. In Carbondale, advocates raised a red flag when they learned that nearly 100 new immigrants, including children, were living under a bridge as winter set in. In the first two months, the task of setting up an emergency shelter fell to the nonprofit Voces Unidas de las Montañas, despite the group’s lack of experience in the area, said CEO Alex Sánchez.

The state later provided a grant of $250,000 and the town government took over management of emergency shelters. But scores of people remain unhoused, Sánchez said, and he feels that the state did not provide enough help with the response.

“Obviously, there's no shelters that they do on a normal basis [in Carbondale], and so everything is learning from scratch, and I think that's been the biggest sort of frustration and disappointment — about how we as a state have not yet learned how to activate and how to support rural communities when it comes to crisis,” he said.

Rep. Elizabeth Velasco, a Democrat who represents the area in the House, said that the state is “paying attention,” but cities and towns need more guidance. “Carbondale, as a small town, they're like, ‘How do we do this? Who's doing the coordination?’” she said. “We must have support from all the state departments. We must respond in humane ways.”

In an email, Carbondale Mayor Ben Bohmfalk praised the state for issuing the grant, and blamed the federal government for failing to act.

Legislative debate ahead

Separately from Polis, another arm of state government appears poised to wade into this debate. Proposed new laws at the state legislature could push Colorado to become more — or less — welcoming to immigrants.

On one hand, Republicans are pushing for increased coordination between local police and federal immigration authorities — an idea that is unlikely to get far in the heavily Democratic body. On the other side, some progressives want to explore ideas like making it easier for some new arrivals to get driver’s licenses.

Lawmakers also control the state’s purse strings and could debate how to distribute the limited financial aid that’s available for immigrants — should it be prioritized for people who have been here longer, or should it include newer arrivals? One Democratic bill would create a $2.5 million grant program to support programs for new immigrants.

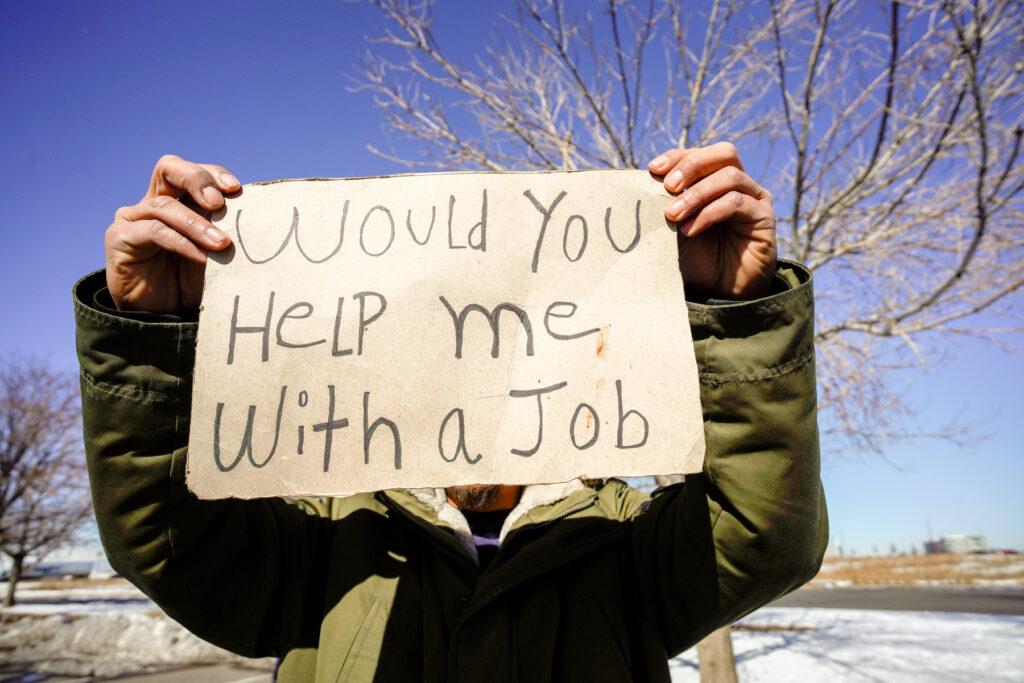

Meanwhile, thousands of people continue to arrive in Colorado each month, looking for new futures. Many said that they fled poverty and political repression.

“The economic situation in Venezuela is not enough for you to have what you need and be able to help your family,” said Miguel, who didn’t give his last name and has been staying at Denver Friends Church for a month, in Spanish.

As young families filtered into his church, Pastor Reeser said he didn’t have the answers for politicians, but hoped that the state government and churches like his could work together to do more. He looked out over the mattresses, each one waiting for the person who would rest there that night.

“Each one of these is a life that is represented from a simplistic mattress on the floor,” he said. “And it's just such an overwhelming experience.”