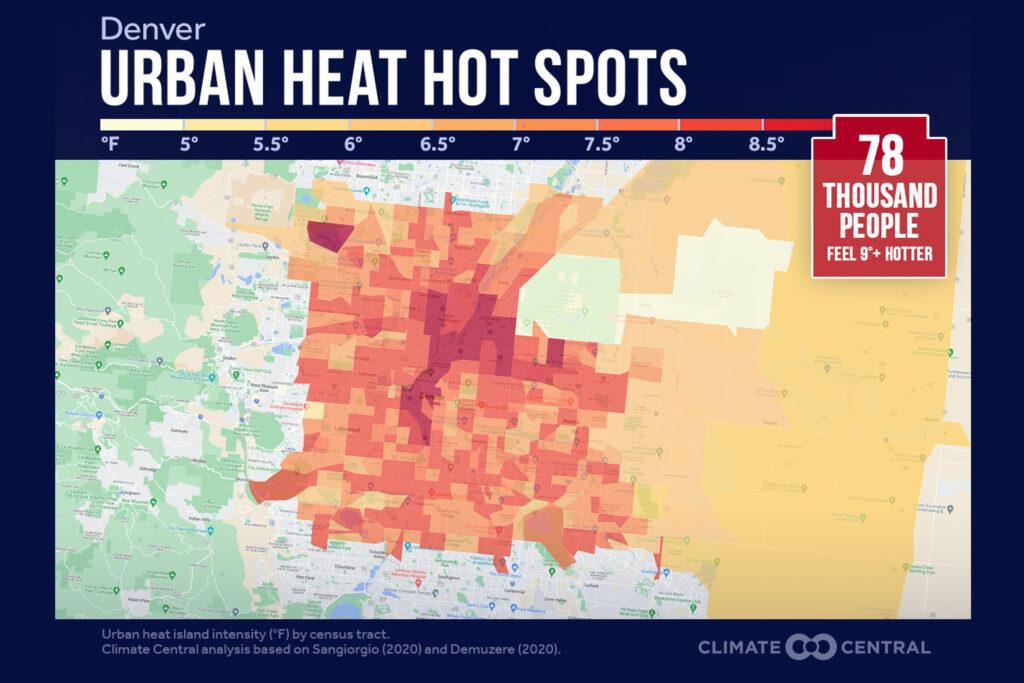

Cities like Denver are getting hotter. Especially neighborhoods that have less green infrastructure. They become urban heat islands. Even if everybody tomorrow started driving an electric vehicle and got solar panels, it’s still not enough to keep the temperature from climbing.

Brad Revare, founder of the Neighborhood Resilience Corps, said Denver is predominantly concrete and asphalt with water-intensive Kentucky Bluegrass lawns.

“Our built environment is not prepared for a hotter, drier, more extreme weather world,” he said.

This is where green infrastructure comes in: more trees to shade concrete; green roofs; permeable pavements; replacing lawns with water-wise plants; new ways to reuse water. There are more state and municipal incentives to replace water-intensive turf with xeriscape lawns.

But right now, there isn’t the workforce for climate resiliency work that is increasingly crucial. With a grant from Denver’s climate office, the corps aims to change that — starting with high school students.

Phase 1: High school field trips to spark interest

“Who knows what stormwater is?”

Denver city planner Chauncie Bigler asked a group of about 20 high school students from Northeast Early College in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood and Vista Academy Green Valley Ranch. They’re gathered on a sunny spot on the 39th Avenue Greenway, a beautiful park and walkway designed for flood control.

Nobody knows the answer, but Bigler said she didn’t at their age either.

When it rains and water hits the pavement it runs off and brings gunk and pollutants into the rivers, she explains. This walkway project through the Cole and Clayton neighborhoods is one of the biggest green infrastructure projects in the city.

One hundred years ago, the area was a river with grass. The city paved it over decades ago. The small pipes during big storms left few places for the water to go and flooding ensued. A few years ago, engineers restored the canal and planted grasses and plants to soak up the chemicals and pollutants before the water goes back into the Platte River.

“Rather than just a huge pipe, you've got a walkway, you've got playgrounds, just a nice place to be, walk the dog, walk the kids,” said Nancy Kuhn, spokesperson for Denver’s Department of Transportation and Infrastructure.

“All these 100 years later, we're realizing, well, maybe nature was right the first time,” added city and county of Denver engineer Colin Bell.

He told the students his career journey started after taking an environmental science class in high school. He was fired up.

“I wanted to change the world, make it better.”

Bell pointed to a nature playground to illustrate how many jobs it took just to build that small piece of the walkway. Building and designing the lights to make sure it’s safe at night, collecting the logs from the forest, designing the playground, designing the lights to make sure it’s safe at night. Somebody had to go out to the forest, cut down the logs and treat the logs.

“Then somebody came out and built the playground with all these logs and rocks and made it look really cool. Somebody planted water-wise plants. Somebody's coming through and weeding. Somebody's making sure it's watered. Just behind us, this sweet playground, 200, 300 people probably worked on it.”

Jobs of the future

Numerous economic analyses suggest jobs in climate resilience and adaptation will number in the millions worldwide. The Denver students visited three sites this spring — and some brought surprises. At Colorado State University’s Spur research center, the students toured a green roof system and a large greenhouse where they learned about hydroponics and aquaponics.

“They use fish poop to grow plants!” Nyimah, 16, exclaimed as her friends laugh.

“Since Colorado is a very dry place, they used the warehouses to grow all these crops, and I thought that was pretty cool,” said Jeffiann, 17.

At each stop on their field trips, workers explain how they got into their line of work and why they were interested in it. The students said they like having more real-life exposure to different kinds of jobs.

“I like seeing the history behind it and why they do it and why they want other people to do it,” Jeffian said.

Manuel, 16, is a junior, and he says people expect him to know what he wants to do with his life.

“But I still want to explore and see my options,” he said. “These field trips really helped me to understand what I could do if I do want to work in one of these types of jobs, and I know that it's going to help my community and be better for the future of the world.”

The students also meet with someone from Groundwork Denver to learn about internships and fulfilling community service hours in things like urban forestry, water conservation and wildfire mitigation.

A trip to the garden and a revelation – tomatoes can get stressed

The kids stand in a semi-circle around Rebecca Peeble, the lead volunteer at one of Denver Urban Gardens' community gardens that is on the site. It’s one of DUG's 38 acres of growing space in the city that helps reduce the urban heat island effect. She explains to the students the meaning of the word “perennial” and explains how food from a garden tastes so much better.

“You have this sense of relationship to the food. And I know that sounds weird, but you’ve been caring for it and watching it become what it's becoming. So you have a sense of why it is the way that it is that automatically makes you psychologically like it more.”

She tells them about the bee boxes to attract pollinators for squash and strawberries, how the Coca-Cola plant donated a tank for water, and how they give surplus bounty to neighbors.

Students ask about her favorite plants. Sweet peas, “they’re crunchy and sweet right off the plant,” and potatoes because you don’t know how many you’ll have, and it’s “almost like opening a gift when you start to dig up potatoes.”

The students seem to be most interested in this fact: that plants can get stressed, from things like temperature or being packed in a truck and having to travel across the country to land in a store.

“When plants get stressed, they don't taste as good,” she said. “Stress makes things taste yucky.”

The students seem to relate to that fact and ask her several questions about it.

Youth are getting more anxious these days, about their futures, about the climate. A survey of 10,000 youth people shows climate change makes two-thirds of them feel sad, afraid, and anxious.

While the field trips have been informative, Angel, 16, said it’s also made him realize how bad climate change is. But the trips have taught him something else.

“That there's many, many ways to solve it or make it a little better.”

Studies also show youth want to explore climate change-related careers.

At the end of the tour, the Neighborhood Resilience Corps’ Brad Revare handed the students a survey to gauge their interest in a career in green infrastructure. Because these students are already in schools that have career pathways, it’s a harder sell. Like Jeffiann who is already studying to be a nurse.

“Honestly, this is not really my career, but I want to make it into a hobby because I do really love flowers and I would want to grow my own flowers in my own home.”

Angel has been focused on studying mechanical engineering. But now, who knows? Maybe civil engineering.

“Learning a little bit about this can help me probably be a civil engineer and make buildings that don't emit that much carbon.”

He’s going to tell his parents about the free gardening classes with Denver Urban Gardens. Others, like Nyimah, appreciated just being able to learn about something new like how water is actually treated.

“I got to see the background around how water is actually produced, more than just seeing water (fall from the sky),” she said, adding that she wants to start eating more plants and vegetables. Another student said the visits made her smarter.

Manuel really liked the visit to Denver’s water recycling plant. Maybe that’s in his future.

“Water is one of the main things we need to survive on this planet, and if we could reuse it over and over again, that could be very helpful for us.”

Two 17-year-old classmates, Kerri and Jeffian, were struck by how much the city and others are actually trying to do to help the environment. It’s not something they hear about in school. Kerri liked seeing how much community garden volunteer Peeble loved working on her plot and Jeffian liked the chance to see people in jobs that they were so passionate about.

“That’s what impacts us, like me personally, is seeing how they're really trying for the environment.”

This summer the Neighborhood Resilience Corps will pilot a climate adaptation training program on a high school campus in Montbello. Another effort will be consulting on Denver Public Schools’ sustainable landscaping plan. And, if it’s funded, the corps wants to launch an apprenticeship model with projects paid for by property owners or in some cases grant funded.

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.