The devastating floods that swept through Texas over the weekend may seem distant, but Colorado has faced similar disasters before — and could again, even if the current risk remains relatively low.

Colorado Climate Center Engagement Climatologist Allie Mazurek said several factors converged in the Guadalupe River Basin to create the perfect storm.

- The ground was already moist from recent rainfall

- Low-level winds trapped the ongoing storm system over one area, creating heavy rains

- Alerts to move to higher ground came while people were sleeping

“The forecasting was pretty good, but there were a lot of challenges. NOAA’s Weather Prediction Center was highlighting the risk of extreme rainfall the night before, and the National Weather Service issued flash flood warnings a couple of hours before waters started to rise,” Mazurek said. “But it's just more difficult to get people to care and be aware of flash flooding. It should be emphasized that climatologists regarded it as our second deadliest weather hazard here in the U.S., second only to extreme heat.”

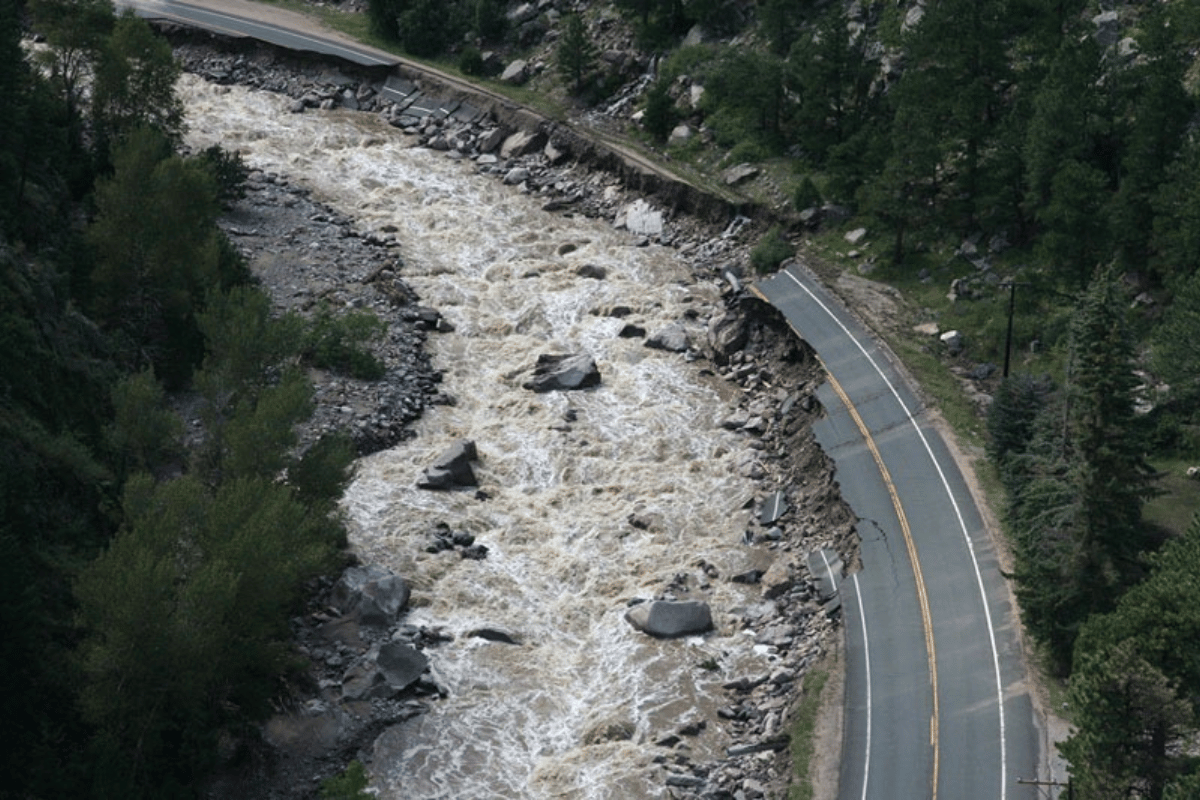

Coloradans know all too well the destructive power of flooding

One example is the 2013 Big Thompson Canyon flood, which killed nine people and destroyed nearly 2,000 homes northwest of Denver.

“The canyon also flooded in 1976, which was one of the worst flash floods in U.S. history,” Mazurek said. More than a hundred people died.

On the night of July 31, 1976, a year’s worth of rain fell on the canyon in just 70 minutes. At the time, more than 3,500 people were estimated to be camping, fishing, and relaxing in the area.

“Lots of those people were in the canyon camping because it was the hundredth anniversary of Colorado’s statehood,” she said.

More than 18 million people visit Colorado state parks each year, with numbers spiking in summer, the same time dual threats of fire season and monsoon season increase the risk of flash flooding.

“We often have people at risk as they're recreating in campgrounds that exist along canyons,” Mazurek said. “Flooding has happened here, and I think the potential is definitely there for it to happen again in the future. We just get them for different reasons than the one that happened in Texas.”

One of those reasons is the state’s monsoonal rain pattern, which can cause flooding in the late summer.

With modern technology, flood prediction has improved significantly, but there are still limitations.

In Colorado, the heaviest rainfall occurs in very isolated areas, and much of the state’s floods are driven by that heavy rainfall.

“Our weather models aren't really sophisticated enough to capture that except on timescales maybe of a few hours,” Mazurek said. “We often know if there's going to be a likelihood of extreme rain, but where and how much is still definitely an area of active research.”

Currently, many rivers across the state — particularly along the Western Slope — are running lower than usual due to a below-average snowpack. But that doesn't eliminate the potential for dangerous flooding.

“We have a very dry area climate here in Colorado, and it really doesn't take that much rainfall to cause flooding. When that happens over a canyon with a river between it, those effects can kind of be amplified further,” Mazurek said. According to the Colorado Water Conservation Board, areas like Boulder Creek, Fountain Creek and some sections of the Front Range are considered particularly vulnerable during intense rainfall events.

Areas with burn scars face even greater risk

“What happens is the land burns from the wildfire and creates a hydrophobic layer of soil that doesn't absorb water very well. On top of that, you have the ash and all of the burned debris,” Mazurek said. “When you get rainfall over those areas, it disturbs that unsettled soil and you can get mudslides and debris flows.”

Should the state experience an active wildfire season and a heavy monsoon season as we move into July and August, flooding risk will increase across the state. However, Mazurek emphasizes that local forecasters and climatologists are always monitoring conditions and working to keep Coloradans safe.

“The National Weather Service offices in Boulder, Pueblo and Grand Junction are all 24/7 staffed. They’re always monitoring our rainfall and our hydrology conditions here across the state,” she said. “Just be weather aware and always make sure you have notifications turned on to receive weather alerts.”