Editor's Note: This story contains mention of self-harm. If you or someone you know is considering suicide or other acts of self-harm, please contact Colorado Crisis Services by calling 1-844-493-8255 or texting “TALK” to 38255 for free, confidential, and immediate support.

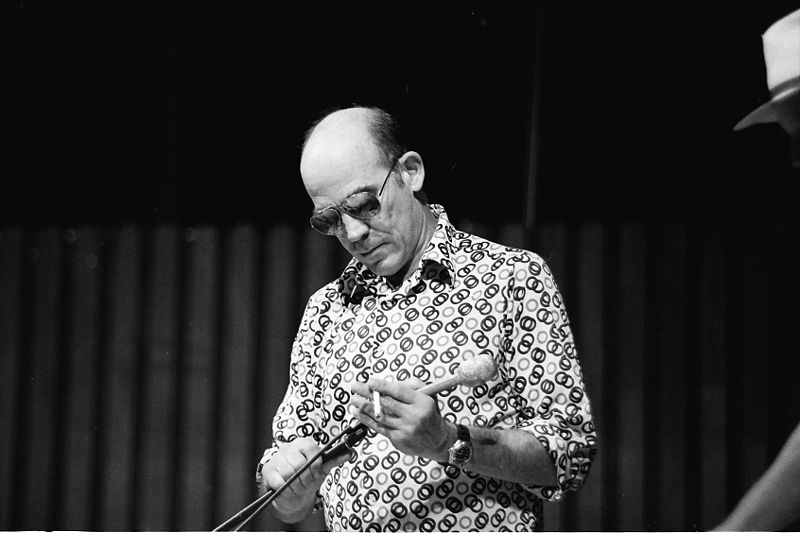

Five years ago, Dr. Anuj Mehta, a physician in the MICU, the medical intensive care unit, at Denver Health and his colleagues faced death every day.

As COVID-19 infected more Coloradans, they worked — in full-body personal protective equipment — to save lives as the hospital filled up.

“At the peak of the pandemic, the floor above us, the entire floor was converted into an ICU and the entire floor here was intubated patients with COVID,” Mehta said, standing in the hallway of the intensive care ward. “And the entire floor upstairs, which is not typically an ICU, it was intubated patients with COVID.”

Many of those patients didn’t survive. “Those were dark times,” he said.

As the virus burned on for the next several years, the death toll soared to more than 15,000 Coloradans lost and drove life expectancy down at a historic rate, the worst since 1943, the nation’s most fatal year of World War II.

But as the crisis eased, and investments in public health, like the broad distribution of coronavirus vaccines, paid clear dividends for the state’s population, Colorado made a breathtaking comeback from pandemic levels. That’s according to the metrics found in an annual summary of death data.

“Even though we're still seeing COVID in the hospital, we're not seeing it in the ICU. We're not seeing it make people super, super sick,” Mehta said. “We do have the one-off cases, and people are still dying from COVID, but it's a lot less.”

Deaths from COVID-19 decreased in 2024 by 40.3 percent compared to the prior year, from 626 to 374, according to data from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. And the life expectancy of Coloradans has rebounded sharply, following improvements in 2023, almost making up for the historic slide.

Between 2023 and 2024, overall life expectancy increased from 79.9 years to 80.4 years, with numbers improving across most race and ethnic demographics. The picture is even approaching the pre-pandemic life expectancy of 80.9 in 2019.

Deaths due to all causes were down in 2024 from the prior year by 0.7 percent (44,862 to 44,527); the age-adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 people declined 4 percent, according to the state’s data.

Vaccines considered a win

Public health experts and doctors point to one major public health win: the rapid development of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines, which rolled out about a year into the pandemic. Nearly four in five Coloradans got immunized with at least one dose by the end of 2023, according to data from the state’s vaccine data dashboard.

“We know that COVID deaths are way down. That's a sign of how well the vaccines have worked and the fact that most people have had COVID at some point,” Mehta said. “So if you get reinfected and have either had COVID or have had all of your vaccines, you're really unlikely to end up in my ICU.”

Just as notably, Colorado saw improvements, as in fewer deaths, across most categories in 2024.

The state also tracks long COVID-19, which is reported as an “underlying cause of death.” For 2024 and year-to-date for 2025, there have been 64 deaths in which long-COVID was mentioned on the death certificate as a contributing factor/condition, or more specifically, “post COVID-19 condition.” This includes 38 deaths in 2023, 19 in 2024, and 7 so far in 2025, according to CDPHE.

Life expectancy up across most racial and ethnic groups

Life expectancy, defined as the average period that a person may expect to live, in Colorado held steady over the decade before the pandemic. Then with the arrival of COVID-19, it fell precipitously for all groups in 2020, especially communities of color, likely due to a lack of access to health care and insurance and systemic health inequities, like where a person works.

Many from those populations were employed as essential workers and living in multi-generational housing, so they were often not able to escape close contact with others, a considerable danger given the virus’s spread via particles in the air. And they faced higher rates of unemployment and less steady access to quality health care, food and exercise.

Life expectancy for all Coloradans fell from 78.6 years in 2020 to 78.1 the next year. As more people developed immunity from getting vaccinated and also catching the virus, the figures started improving, rising to 80.4 years in 2024.

Life expectancy for Black residents rose from 72.8 in 2020 to 76.5 in 2024. For Hispanic Coloradans, it rose from 75.8 in 2021 to 80.2 in 2024. It increased from 79.2 in 2021 to 81.1 in 2024 for white Coloradans.

Other groups generally saw increases, or if a decrease, a slight one.

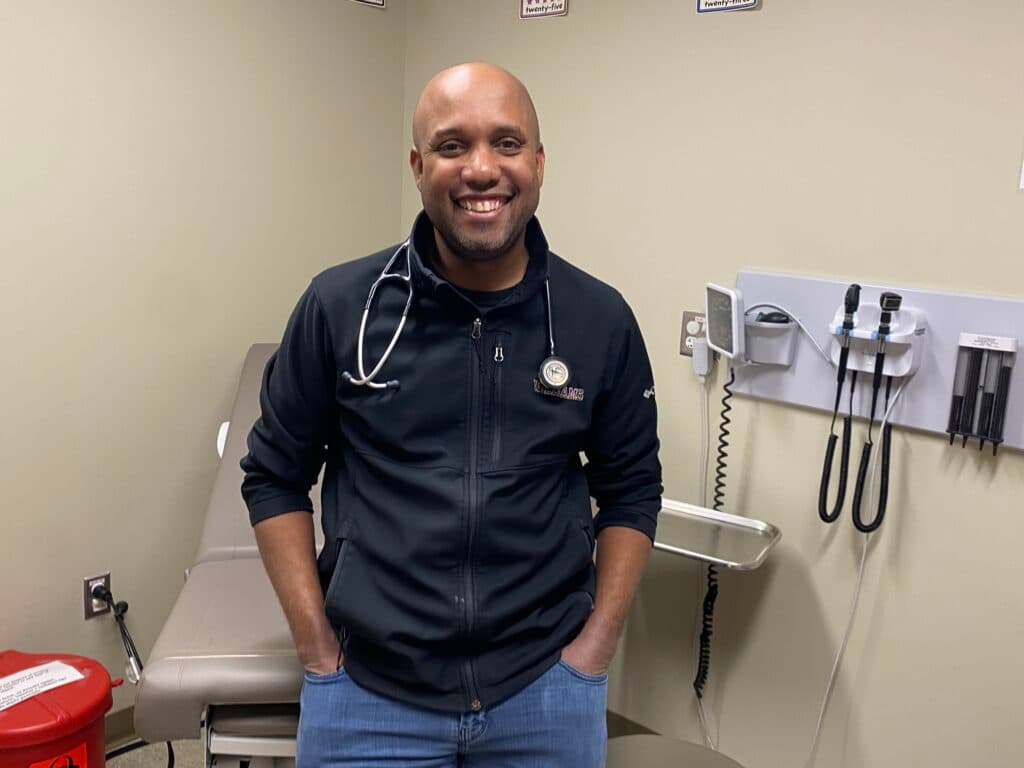

“We've had a robust response from public health,” said Dr. Tamaan Osbourne-Roberts, a practicing family physician in Aurora who serves a diverse population, and the first person of color elected as president of the Colorado Medical Society. “We've had a robust response from clinicians like myself, continued work at vaccination, a whole lot of things to try and drive that number (of COVID-19 deaths) down.”

Deaths in most categories, including overdoses, fentanyl and accidents, also fell in 2024

Perhaps most remarkably, deaths across a variety of categories besides COVID-19, except for suicide, also fell, in some cases considerably, according to the state’s data, which is published on its website.

Many categories of death for Coloradans remain high. Hundreds of people still died from homicides, about a thousand from firearm-related injuries, around 1,300 from suicide, and more than 1,600 from drug overdoses.

But the numbers reveal improvements.

Those included deaths from homicides (down nearly 17 percent), from drug overdoses (down by 14 percent), involving fentanyl (down nearly 31 percent) and from motor vehicle crashes (down by 4 percent.)

The total for suicide deaths did not change significantly.

“As someone who does injury prevention work, I'm really excited to see the decrease in overdose deaths and in firearm-related deaths,” said Dr. Marian Emmy Betz, an emergency physician at UCHealth Emergency Care and founding director of the Firearm Injury Prevention Initiative.

Multiple factors likely in play

Why the figures improved isn’t exactly clear, according to doctors and public health experts CPR spoke with. Perhaps broader societal and post-pandemic behavioral patterns could have played a role. Another factor could be a steady and large infusion of federal funds nationally during the Biden administration into health and community programs. Also, the government allowed people to stay enrolled in health programs like Medicaid during the early years of the pandemic. That swelled the rolls and also gave people access to regular and preventive care.

After the sharp rise in overdose deaths in Colorado and nationally, a variety of public health approaches have been used, like increased education, community outreach to high-risk populations, and the wider availability of the overdose reversal drug naloxone, also called Narcan.

“I think public health is really about the work of the whole public, about promoting the health of the public,” Betz said. “And those are broad approaches. So sometimes it's better streets or better access to groceries, education in schools, access to health care.”

“One of the things that comes up for me is the decreased homicide rate. We've seen a substantial drop in that due to a range of different programs and other things that have happened in the past several years,” said Osbourne-Roberts. “That has been really promising to see.”

Betz said the decline recorded in firearm-injury deaths is probably due to multiple factors, including the drop in homicides, which account for about a quarter of firearm deaths.

“Maybe newer, better approaches to community policing, maybe interventions to help get youth out of a cycle of violence where they might be at risk of hurting someone else or being hurt,” she said. “It's not a single intervention that worked, but it's really about helping communities be safer. And that's fantastic.”

Others are already seeing signs 2025 may not see the favorable trends continue. For example, confirmed overdose deaths in Denver, through June 6, rose nearly 22 percent, to 273, according to the city health department’s website.

“While there was a slight decrease in 2024, Denver has really had an increase in overdose deaths since March,” said Lisa Raville, the executive director of the Harm Reduction Action Center, via email. “We are very concerned about the large uptick in overdose deaths, primarily public, in Denver.”

She said she wasn’t sure why there’s an increase. “We have an incredibly unregulated drug supply with many different drugs in the fentanyl supply,” such as zylazine, she said.

Raville said a few immediate changes could help, like on-site drug checking, overdose prevention centers, a safe/regulated drug supply, and methadone access in pharmacies, ideas that would need to win broader support in order to implement.

Storm clouds on the horizon

In its first six months, the Trump administration has made deep cuts to research, along with steep cuts in the Congressional budget bill, to safety net health programs like Medicaid and SNAP. So far, the administration has decided not to extend tax credits to people buying health insurance on state marketplaces. It cut funding to public health and a broad array of community programs. It’s made controversial changes to vaccine policy and decision-making.

Some say the cutbacks could show up in Colorado’s death data in future years.

“I am absolutely worried about seeing a reversal,” said Osbourne-Roberts.

“Certainly we're worried about stability of funding, not just for programs like ours, but for the organizations on the frontline and for state and local agencies, for example, to be able to collect data, to understand what's going on,” Betz said.

Mehta worries people will be unable to access health care and will end up needing to go to the hospital with worse conditions.

“I am terrified. The number one concern that I have is the recent legislation to cut Medicaid eligibility,” he said. About half of the patients at his hospital, Denver Health, the state’s flagship safety net facility, are enrolled in Medicaid. “I mean, not having health care is going to lead to huge implications for their health outcomes, the state's life expectancy and death rates,” he said. “But also so much of the U.S. and Colorado population is one health care emergency away from bankruptcy and foreclosure.”