So many Coloradans died of COVID-19 and related causes, including drug overdoses, that life expectancy statistics fell dramatically this past year.

The drop was most alarming among communities of color, where enough Hispanic and Black residents died in the pandemic that both groups’ life expectancy statistics fell by about four years. The drop among white people in Colorado was 1.4 years.

The state health department released the data Thursday afternoon, showing overall life expectancy in Colorado dropped by a full two years, from 80.9 years in 2019 to 78.9 years in 2020.

Life expectancy is a statistical average of all people in a particular geographic area or demographic group. It is not a predictor for individuals. The life expectancy for people who have lived through the pandemic has not changed.

But the state data mirrors a new national study showing life expectancy plunged for Americans, declining 8.5 times more than the average for 16 peer high income nations between 2018 and 2020. That study was co-authored by researchers at CU Boulder, Virginia Commonwealth University and the Urban Institute, and published in the BMJ, the journal of the British Medical Association.

“This is critical because we are losing years off certain vulnerable populations' lives. It should never happen in our country,” said Dr. Ozzie Grenardo, chief diversity and inclusion officer at Centura Health.

Speculation around the national study was that COVID-19 exposed and exacerbated the longstanding differences between access to health care for white Americans and access for people of color. On top of that, more Black and Hispanic residents of the U.S. worked in frontline jobs throughout the pandemic, exposing them more often to the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

“My thought was that this is incredibly sad,” said Dr. Tamaan Osbourne-Roberts, a family medicine doctor who serves a diverse population at an Iora Primary Care clinic in Denver.

He noted the latest research underscores what he’s learned and observed in his clinic, where many patients skipped or delayed getting needed care.

“We certainly are seeing the same difficulties with chronic care that played out prior to the pandemic being made worse by the pandemic.”

People of color have been impacted harder by coronavirus since the beginning of the pandemic.

Colorado is now approaching 7,000 deaths due to COVID-19. In the early days of the pandemic, those deaths were occurring disproportionately among Black and Hispanic residents.

Over time, the official statistics have moved the percentage of deaths in both categories closer to the actual representation in the population. But almost five percent of death cases are still listed as “unknown” ethnicity.

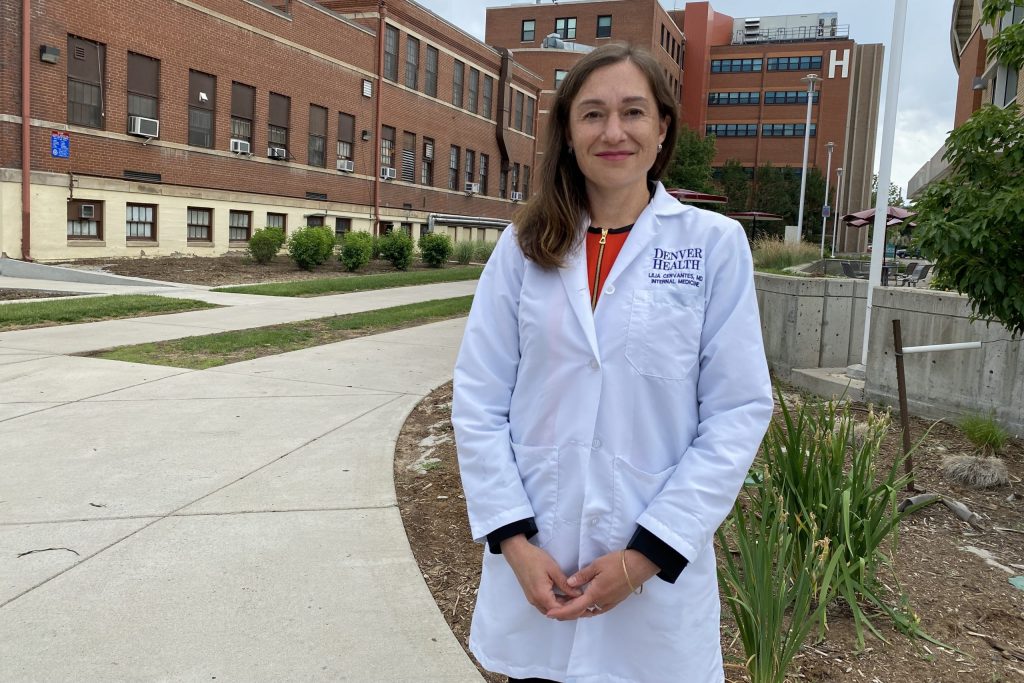

“I'm not surprised. I'm not surprised at all,” said Dr. Lilia Cervantes, an associate professor in the department of medicine at Denver Health.

She noted that since the pandemic began the U.S. has seen a “disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths in our Latino and Black communities. The same issues that the rest of the nation had are especially prevalent in Colorado.”

Deidre Johnson, CEO and executive director of The Center for African-American Health in Denver said the conditions of the pandemic created the perfect opportunity for the virus to exploit the health inequities people have been talking about for years.

“This is heartbreaking, yet not surprising,” Johnson said. During the pandemic it was easy to delay regular preventive care visits, dental care and hospital visits as everyone was trying to stay as safe as possible. Some providers and media even recommended delaying care, she said.

“It also became harder to access care if you were in need,” Johnson said. “COVID-19 was a perfect storm of health inequity within a stressed health care system.”

The data released by the state show life expectancy in Colorado holding steady over the past decade and then falling precipitously for all groups in 2020. For Hispanic residents, life expectancy dropped from 81.4 years to 77.3.

Black Coloradans saw life expectancy drop by almost the same amount of time, from 78 years to 74.1 years.

Asian/Pacific Islander life expectancy fell from 88.8 years to 83.8 years and American Indian/Alaska Native expectancy slid from 83.4 to 80.5 years.

For white Coloradans, the drop was from 81.5 years to 80.1 years.

“Certainly COVID played the most significant role in this, as likely did increases in such causes as drug overdose,” said Kirk Bol, the manager of the state’s Vital Statistics Program. He noted that for Asian/Pacific Islander and American Indian/Alaska Native populations, with their relatively smaller populations and few overall deaths, “life expectancy estimates become less reliable.”

CU researcher Ryan Masters, one of the BJM study’s co-authors, said a lack of equitable access to health care and other inequalities are key factors.

"It's devastating, or horrific — an absolute tragedy. One that we probably could have seen just because of the deeply rooted systemic factors," he said.

Systemic inequalities — from who has access to health insurance to where someone lives and works — have helped drive the inequalities.

One gauge of those underlying disparities is the uninsured rate. In Colorado in 2019, 15.6 percent of Hispanic residents and 8.6 percent of Black residents were uninsured, compared with 6.8 percent of white Coloradans. That’s according to data compiled by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Cervantes spotlighted the greater risk people of color have to COVID-19, what she described as “structural inequities that increase exposure” to coronavirus.

Many are employed as essential workers and live in multi-generational housing, so they’re often not able to escape close contact with others, a considerable danger given the virus’ spread via aerosol transmission. And they face higher rates of unemployment and less reliable access to quality healthcare, food and exercise.

Plus, she said, marginalized groups that also have a “prevalence for the cardio-metabolic conditions that increase the risk for worse outcomes” from COVID-19, things like obesity, diabetes and hypertension.

“How long you live depends on where you live in this country, your zip code, and is a measure of how healthy we are as a nation,” Cervantes said.

She spotlighted “social determinants of health” as key factors in life expectancy. These are the “conditions in the environment in which people are born, live, learn, work, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health and quality of life outcomes like life expectancy or life span.”

She said research has shown those things are responsible for an impact of some 70 percent towards how long we live, compared to social circumstances, environmental exposure, healthcare, and behavioral patterns.

Cervantes grew up in the largely Latino Valverde and Westwood neighborhoods in Denver, areas close to I-25 with few parks and grocery stores. Citing pre-pandemic data, she said “it's morally distressing to think about how there is a 6-year life expectancy difference” between Valverde (78 years) and the mostly white Washington Park neighborhood (84 years) even though they are less than 5 miles apart.”

Cervantes thinks those gaps only worsened during the pandemic. “We need to invest more as a nation in social services,” she said.

The new data is just the latest in a grim parade of misery caused by the pandemic and the underlying inequities that made it so devastating, especially in vulnerable communities.

Where the additional deaths came from, and what must happen next to remedy the life expectancy disparities.

Besides deaths from COVID-19, Colorado recorded hundreds of additional deaths, which appear to have at least an arm’s length connection to the pandemic as people self-medicated for anxiety and depression or chose to avoid health care and other human interaction out of concern for infection.

Causes like drug overdoses, Alzheimer’s and liver diseases, starvation, and parasitic diseases all experienced double-digit percentage increases in 2020. That’s above the average number of deaths from the causes in the three years prior to the start of the pandemic.

Health leaders and community advocates say now that this new data is out, it’ll be up to Coloradans, and Americans, to remedy the stark disparities that bring shorter lives to millions of Americans, compared to their counterparts in other wealthy counties.

“We're all interconnected. This is all interlinked,” said Osbourne-Roberts. “The health of one population in our country affects the health of all populations in our country. And that being the case, it is my hope that people will see that and really begin to address all the drivers of health amongst all Americans.”

The first order of business is to improve vaccination rates in communities of color, said Grenardo, a member of the state’s Vaccine Equity Task Force.

To date, in Colorado and the U.S., COVID-19 vaccination rates in those communities trail the white population.

“It really is truly another call to action for us to do something and make sure that we are vaccinating our populations who are most at risk for having issues with becoming infected,” Grenardo said. “If we don't do something about it, then certainly those numbers will continue to get worse.”

'If this doesn’t bring shock and alarm to how poor the U.S. is doing in terms of population health, I don’t know what will'

The BJM study stated the U.S. hasn’t seen such a drop in life expectancy this large since 1943, during World War II.

The declines among Black and Hispanic Americans are especially troubling, said Masters. He said after years of experiencing higher life expectancy than white men, Hispanic men saw that advantage erased in 2020.

In 2020, life expectancy in the U.S. Black male population was 68, the lowest it has been since 1998.

“If this doesn’t bring shock and alarm to how poor the U.S. is doing in terms of population health, I don’t know what will,” Masters said.

In another worrisome trend, he said the U.S. also recorded an unusually high number of younger people dying in 2020, with the majority of life expectancy lost among the male population due to deaths below age 65.

Some other countries, like Italy and Spain, also saw losses in life expectancy. But none were close to the magnitude the U.S. saw. New Zealand and Norway even saw life expectancy rise in 2020.

The study did not examine only deaths caused directly by COVID, a number that can be difficult to calculate, but instead looked at all deaths that happened in 2020.