Seventh-grade math teacher Greg Meshell started off a new school year in Cortez on Monday, knowing that every penny he earns keeps a roof over his head.

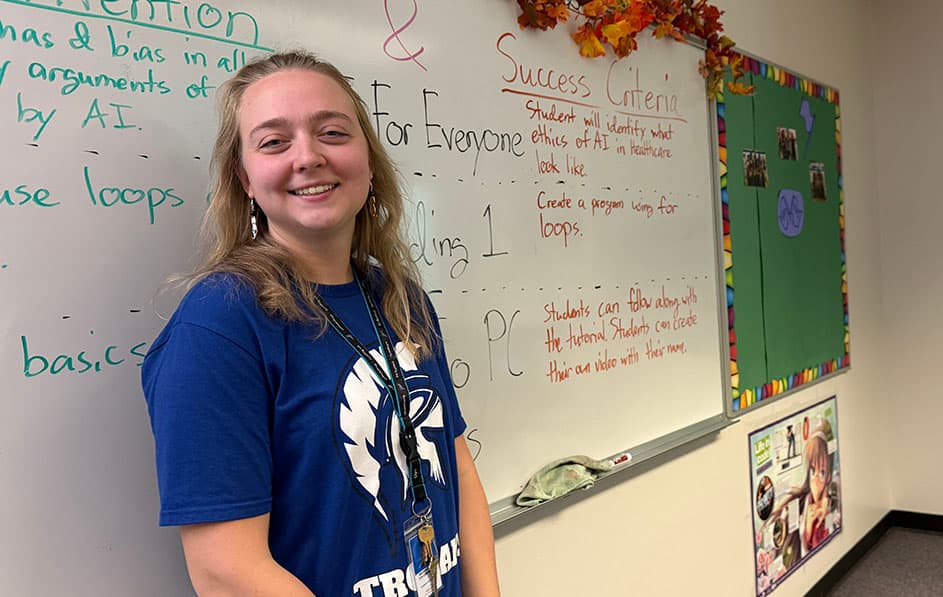

Even with 27 years’ experience, even with a pay raise, his rent takes up 42 percent of his salary. Another Cortez educator, first year teacher Cassidy Proctor, who has a Master’s degree, needs her parents' support to survive. She earns $44,000 a year. Teachers across Colorado, like Proctor and Meshell, are increasingly being priced out of the communities they serve.

Their stories are among those featured in a new first-of-its-kind report showing Colorado’s housing affordability crisis is threatening the stability of the state’s public education system. It finds teachers are spending unsustainable portions of their income on rent, delaying homeownership indefinitely, commuting long distances, or leaving the profession entirely.

In some districts, more than half of educators spend more than 40 percent of their income on housing, according to the Keystone Policy Center’s research.

“Colorado’s ability to deliver quality education depends on having committed, effective teachers in every classroom,” said Van Schoales, the center’s senior policy director. “Without affordable housing, we will continue to lose great educators. This report includes firsthand stories from across the state that make this hardship impossible to ignore.”

The report, “We Can’t Live Where We Teach,” is Keystone’s third major publication on teacher housing since 2022. This year, it includes data from a survey of more than 3,200 educators across the state, concluding that the lack of affordability is a major reason behind the state’s teacher shortage. It calls for a coordinated effort to develop more affordable housing if Colorado wants to overcome its chronic teacher shortage.

The report had several key findings:

- Most teachers (58 percent) were interested in district-provided housing. Most of those who were not interested were already homeowners.

- Seventy percent of teachers were comfortable with the district acting as landlord.

- Affordable housing in a school district would likely encourage teachers to stay, while a scarcity of it would make them more likely to leave for another district that offers housing.

- Teachers report leaving the profession for better-paying work in other industries, often with less stress and shorter hours.

The report conducted in-depth interviews with multiple teachers and other school employees, painting a sobering picture of how housing is inextricably linked to maintaining teaching staff.

Sabra Day, a school administrative assistant in Durango, and her husband lived for four years in a two-bed, two-and-a-half bath rental for $1,850 per month, a bargain by local standards. But the couple was on the precipice of leaving the city after Day’s husband had to take a $40,000 pay cut to switch jobs.

Day luckily found a more affordable place through a connection at work. The couple now live in a two-bed, one-bath house for $1,300 per month. The place normally rents for $1,600, but the school employee got a reduction because of her personal connection, according to the report.

Some staff resort to commuting. Autumn Green, who coordinates substitute teacher placement in Durango, commutes 20 miles from Bayfield. She shares a modular home for $2,200 each month, or about 24 percent of her income for her portion. She estimates sharing a comparable two-bedroom apartment in Durango would cost her between $2,500 and $3,000 monthly.

“Most people have to have at least two or three incomes to actually have a home,” Green told the report’s authors.

She said Durango has seen an exodus of talent because of the cost of housing. Another Durango district staff member, Nathan Van Arsdale, said the first three friends he met in town (“very dynamic, intelligent, hardworking”) all used to be teachers. They all left for other jobs.

“Two of them work for one of our car dealerships in town,” he said. “One of them is now a server in a restaurant. They all make more money than they did teaching. They also have more freedom, because they don’t have to work as many hours.”

Many rural districts are increasingly relying on international teachers to fill positions. Those teachers are also feeling the pinch. Leah Corporal from the Philippines said she must share housing. She pays $750 a month for a single room in a house with another Filipino teacher’s family. Some of her colleagues are in even more crowded situations.

“Four young ladies from the Philippines moved into a two-bedroom house,” said Corporal. “Four girls who didn’t know each other were sharing beds in two different rooms,” she said, adding that even after sharing, there’s not much left of their salaries.

Teachers less likely to leave if housing provided by district

The report found that districts like Byers School District that provide housing for their teachers allow them to compete with neighboring districts that have shifted to four-day school weeks.

Superintendent Tom Turrell manages 10 apartments and two houses for employees.

“We don’t have a lot of turnover,” said Turrell. “When my teachers are there, they realize the benefit, and there’s a lot of loyalty that comes with that.” He told Keystone researchers that teachers can also save about $1,700 a month because their rent is between $250-$350 a month.

The waiting list for housing follows strict priorities: First through third-year teachers take precedence, followed by more experienced teachers, then support staff. He said some school boards have been skittish about becoming landlords. But he says renting to teachers has never posed problems.

“My view is sometimes we’ve got to do what we’ve got to do, and it’s just one more hat to wear. We wear plenty of them.”

Vilas School District manages 11 district-owned rental units.

Recommendations:

- School districts must collaborate with teachers to understand their housing needs.

- School districts should study successful housing initiatives from other Colorado districts and across the nation.

- School districts should consult outside consultants and organizations to help navigate housing initiatives.

- The state and non-profits must play a role in bringing people, information and resources together.

The report also names other solutions tried by some school districts across the country: converting existing buildings no longer in use to teacher housing, building housing on district- or city-owned land, partnering with private building owners to subsidize rent, serving as a landlord or partners with a commercial landlord, and programs to support teachers with homes.