A decade ago, youth arrests for violent offenses in Denver’s Park Hill neighborhood were high compared to the national average — working out to one in every one hundred teens in a single year. That’s when the Youth Violence Prevention Center–Denver set out to test an innovative intervention program.

Could doing more to connect teens to their neighborhood and being more vigilant about spotting the ones headed for trouble cut crime rates?

The results were promising — a 75 percent decrease in youth arrests for violence.

“Seeing that 75% reduction ... that drastic decrease was very wonderful,” said Beverly Kingston, the director of the prevention center and one of the leaders of the effort. “That's one of the happiest things in my career to actually have the numbers along with it.”

However, this study, more than a decade in the making, could end without reaching its full potential. Both the center and its research are funded through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under public health efforts that the Trump administration is in the process of defunding and dismantling.

Research with real-time impacts

The study and the center are both part of research being conducted by the Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence at the University of Colorado Boulder. The research is around what kind of interventions can lead to meaningful drops in violent crime.

“This kind of research is rare, and I wish it wasn't this way because it is so valuable to do work this way. We're working in partnerships with the community, so there's this implementation part of it,” Kingston said. “It's not only a research study, it's full of resources going into the community.”

The intervention effort of the recently released study focused on two Denver neighbourhoods, starting from Montbello in 2012 and northeast Park Hill in 2016, and running until 2021.

“We were implementing something called Communities that Care, which is all about the community coming together and getting organized to prevent youth violence,” Kingston said. “They formed coalitions, they implemented different community-level strategies that were designed to address the specific risk and protective factors that their communities were struggling with.”

The two separate neighborhoods were given different implementation plans, but both had an emphasis on strengthening neighborhood attachment through things like media campaigns and social development strategies. Kingston said that’s important because being connected to their community can help young people stay out of trouble.

“Being bonded to your community, having those kinds of identification with place? That can be a protective factor,” Kingston said. “And so what we're aiming to do is help the young people feel that.”

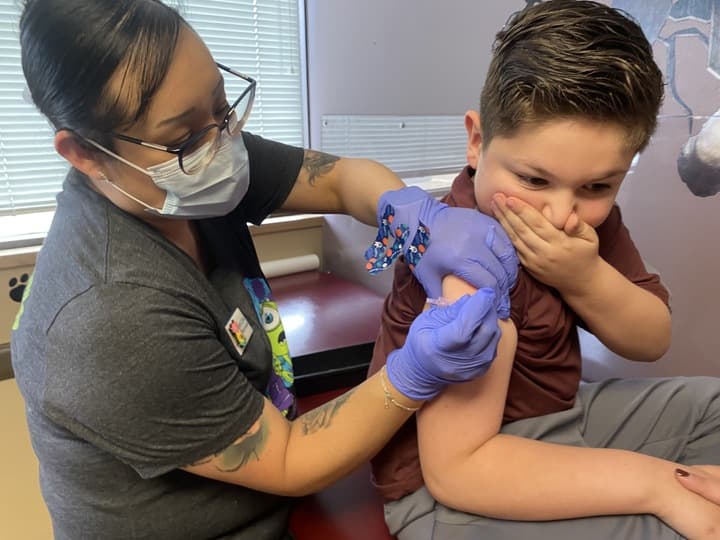

The study also worked with doctors and other medical staff serving the neighborhood to start using a standardized screening tool to identify the youth most at risk of violence.

“If kids score high, prior research shows that they're at higher risk for violence one year later,” Kingston said. “So the idea is then to get those young people the support that they need. If they're supported, there's no reason why they will ever need to get involved in violence. It really is to work much more upstream.”

To measure whether the interventions worked, the researchers tracked and synthesized youth arrests across 76 other Denver neighborhoods. Arrests did decrease in those neighborhoods during the study period, but by less than 100.

Whereas in northeast Park Hill, youth arrests decreased by more than 800.

CU Boulder’s violence prevention center was created after the Columbine shooting. The center was funded by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which in recent decades has invested in looking into how to address youth violence. CU Boulder is one of five universities across the country funded to do studies like this.

However, the future of that funding is no longer certain.

Layoffs and paused funding are already in effect

The Trump administration has proposed major funding cuts for the CDC, which have yet to be approved. But already, the CDC is going through major staffing cuts. The Division of Violence Prevention that the Denver study falls under, “has pretty much been gutted,” according to Kingston.

“The whole infrastructure, the staff that worked in partnership with us for years all lost their jobs,” Kingston said. “They’re gone.”

The center is currently funded by a five-year CDC grant, with the final year's funding, $1.2 million, scheduled to go through on September 30. But, Kingston said, they have no idea if that’s going to happen.

“We're told that the funds are not going to be released. But it's not been official,” Kingston said. She added that no one knows what grants or funds, if any, will be available next year.

Kingston said that the final year of a study is imperative. It’s when they can quantify the results of the years of work and put their conclusions together into the study.

“To demonstrate that impact, the final year is all about evaluation and being able to then collect the data, analyze the data, and then disseminate the findings,” Kingston said. “So really, the fruit is ripe on the tree and it's now going to die in the vine.”

| This story is part of a collection tracking the impacts of President Donald Trump’s second administration on the lives of everyday Coloradans. Since taking office, Trump has overhauled nearly every aspect of the federal government; journalists from CPR News, KRCC and Denverite are staying on top of what that means for you. Read more here. |