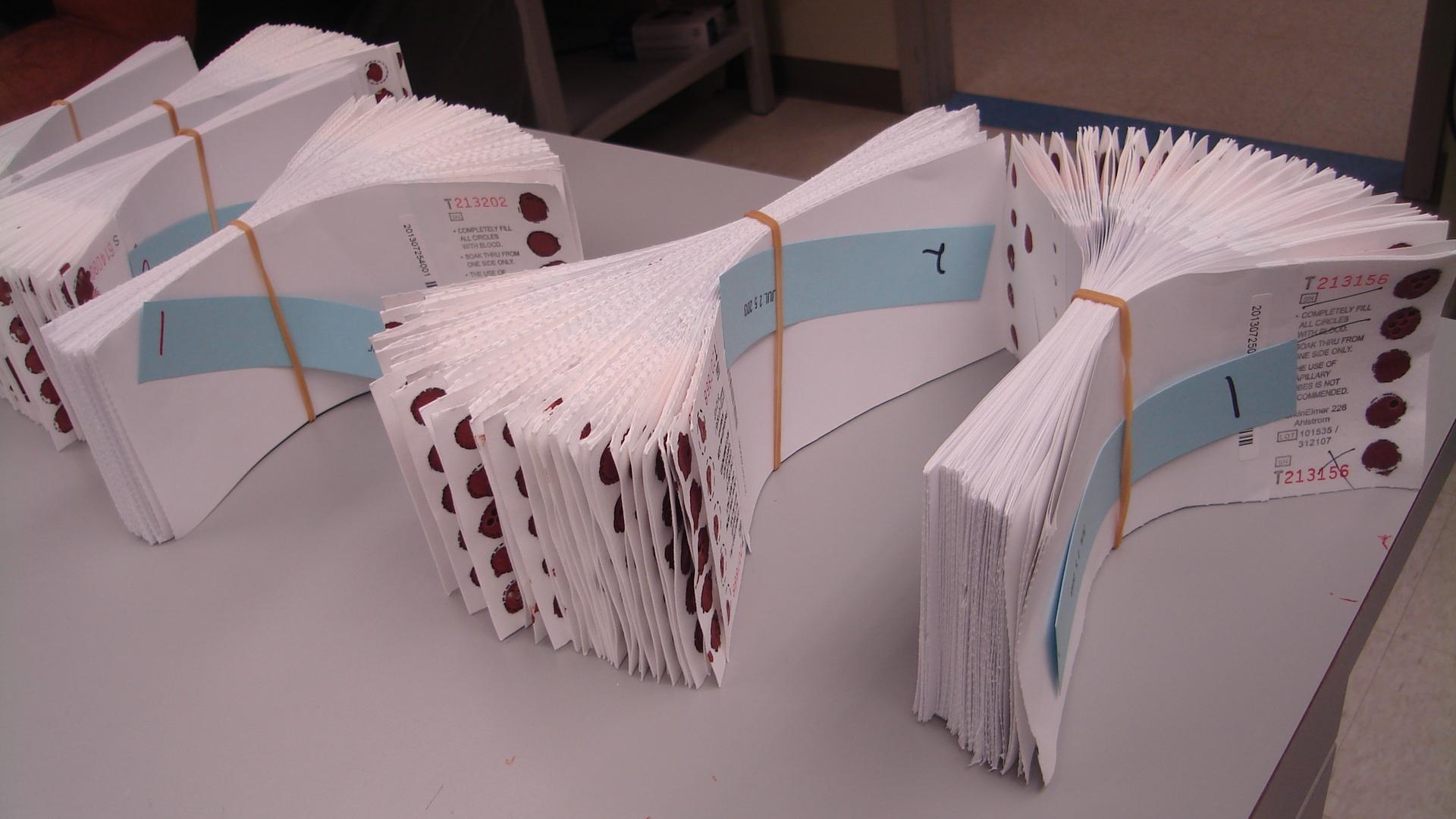

Newborns in Colorado are screened for a series of genetic disorders. Some of those disorders can have severe consequences not long after birth. Yet until now, the state lab that processes the screenings was closed on weekends, creating a delay that could be fatal in some cases.

Starting this weekend, the state lab is adding Saturday hours to process newborn blood tests. The expanded hours reflect new national recommendations for the timeliness of newborn screening.

"We used to think testing should be done within a week," says epidemiologist Marci Sontag, who sits on the state's newborn screening advisory committee. "Now we’d like to aim for two to three days.”

Adding Saturday hours will cost about $81,000 per year, according to Laura Gillim-Ross, laboratory director at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. The cost of screening is paid for by test fees, which are usually covered by insurance.

Gillim-Ross says the state is taking other steps to speed test results. It’s made a courier service available to hospitals to deliver blood tests to the lab in Denver. And its working with the Colorado Hospital Association to educate medical professionals on taking the blood samples promptly and correctly.

Nationally, problems with delays in newborn screening were brought to light by a 2013 investigative report by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, which profiled two Colorado babies born with the same genetic disorder. The baby born on a Tuesday was screened promptly and lived and the baby born on a Friday died before test results identified the problem.

The Saturday hours come as Colorado marks the 50th anniversary of newborn screening. The state first began screening for the metabolic disorder phenylketonuria, or PKU, in 1965. Since then, the list has expanded to 36 disorders, including sickle cell anemia and cystic fibrosis.

“To families that find out that their baby has a disorder before there are tragic consequences, it’s a life saver,” says Sontag.