On Memorial Day we have stories of the very best wartime pilots, America’s fighter aces. To earn that distinction, they had to have destroyed at least five enemy planes. Some 60,000 combat pilots served between World War I and the Vietnam War -- only 1,447 became aces.

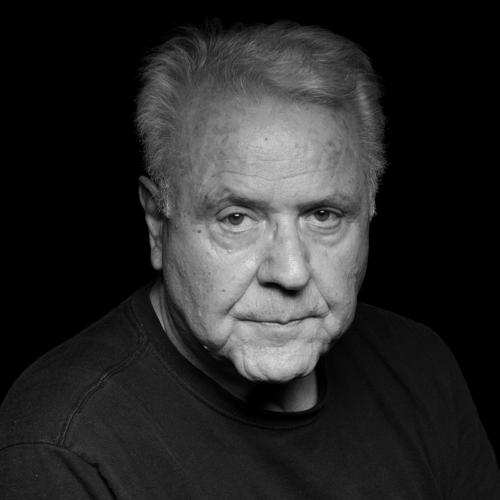

Captain David Wilhelm of Denver is one of them. He flew the agile P-51 Mustang in World War II. Wilhelm, now 98, says the P-51 was the best plane to be in when he fought the Germans.

"When our bombers would head to bomb their oil facilities or factories they were attacked by a horde of German 109 airplanes so our mission was to keep those Nazi airplanes from shooting down our bombers," he says.

That wasn’t easy. The fighter pilot didn’t just fly the single-engine plane. As the only one on board, he was also navigator, often flying for several hours to reach his target.

"We’d have to get to our target without any modern present day electronics. We did almost by just a straight compass reading -- by today’s standards very elementary," Wilhelm says.

He had to be his own gunner too. Getting behind enemy aircraft was critical for the best shot during aerial battles known as dogfights.

"You wanted to be damn sure he didn’t get on your tail. Because if he got on your tail, you had to work like the devil to keep from getting hit by his shooting. So we’d be contorting up and down and around. It was either you’re going to get shot down or you’d shoot him down," he says.

Wilhelm shot down six Nazi planes over eastern Europe in 1944. He says, unlike a lot of the other aces, he can’t reconstruct the details of the battles. He had to rely on pilots who witnessed his victories or the camera mounted on his plane. After the war, he bought and ran a cattle ranch in Fraser.

Wilhelm is among the aces profiled in the book “Wings of Valor: Honoring America’s Fighter Aces,” by Denver photographer Nick Del Calzo and writer Peter Collier.

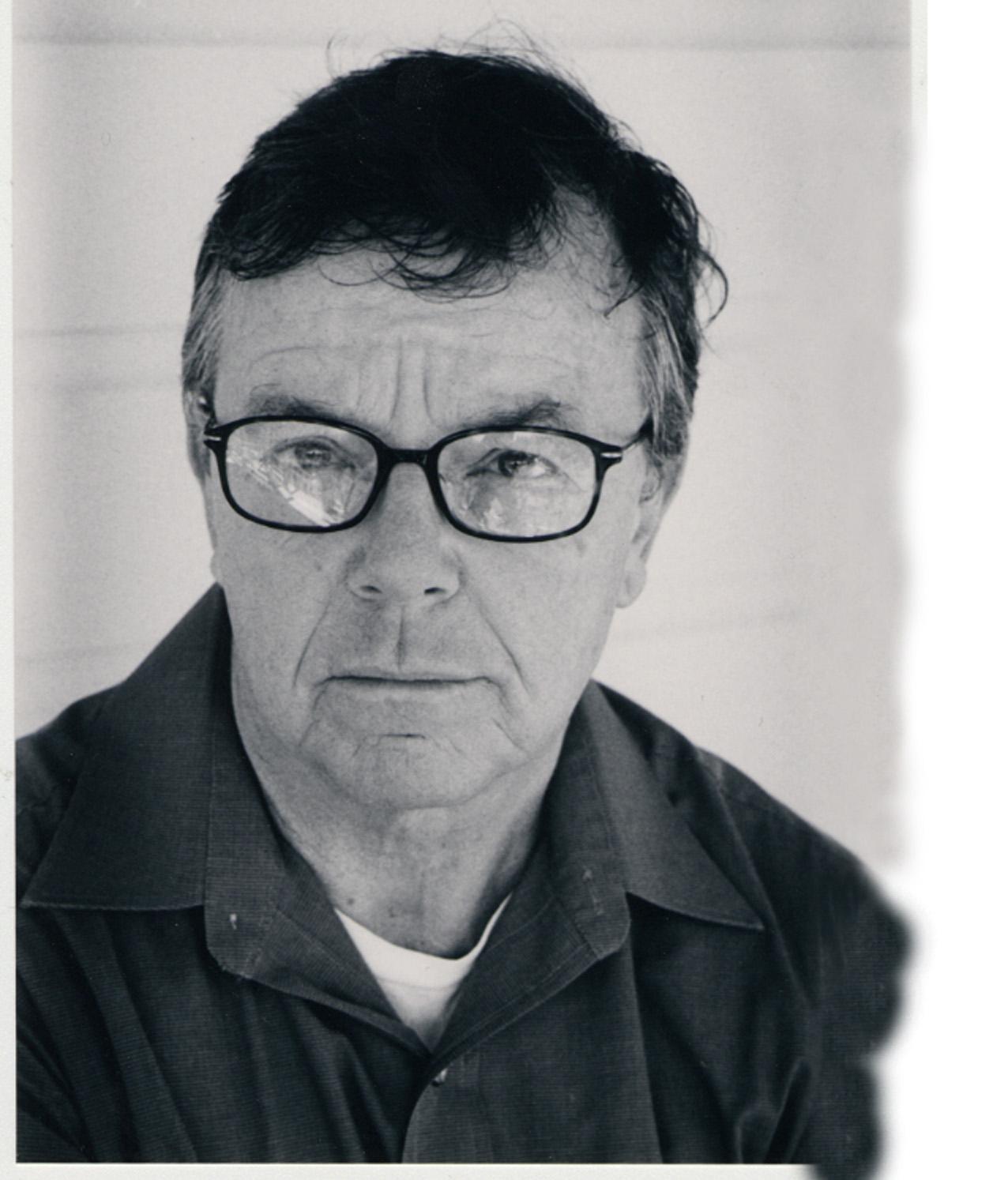

Also in the book is the man who may be one of the last American pilots to become a fighter ace, retired Air Force Reserve Brig. Gen. R. Stephen Ritchie of Seattle. During the Vietnam War, the Air Force Academy graduate and longtime Colorado resident flew 339 missions in the F-4 Phantom.

He describes the day he shot down two enemy MIG jets. "We met head on at over 500 mph each .... And we go into a maneuvering fight to try to get behind each other. This all takes place in a total of a minute and 29 seconds."

Ritchie says it’s hard to explain what it’s like to be in this kind of high-tech aerial battle that takes place all around you.

"If you haven’t been in that three-dimensional sphere and experienced all of the pressures: the g forces, the speed, the visual requirements, the hearing requirements, all of the different types of communications or the surface-to-air missiles, the anti-aircraft artillery. All of things that can go wrong, all of the things that can go right. There’s no way to describe it," he says.

Ritchie says there are any number of reasons he might never have shot down five enemy planes and become an ace, not the least of which was the unreliable nature of the missiles he used; they only worked 11 times out of a hundred. He fired three. The first two downed one enemy MIG and the third hit a second enemy jet.

"I was too close, I was pulling too many gs .... so I had three perfect missiles under those circumstances and the chances of that are virtually zero," he says.

Ritchie also had many brushes with death during the Vietnam war, like the time he got hit by an enemy shell.

"The angle of that shell was so perfect that it came into the intake -- it went through the engine took out a bunch of rotor blades and went out the rear of the engine. The likelihood of that? Probably ten thousand to one. The likelihood that it didn't cut fuel and hydraulic lines and the airplane didn’t come apart, which is what should have happened ... but the airplane stayed together and flew back to DaNang and landed safely. "

He says surviving close calls like that made him grateful. But it also makes him wonder why he made it and his best friend didn’t. His friend Woody died when a plane piloted by someone else went down.

Ritchie says, "How come I had all those close calls and survived? And ended up being victorious and had all this publicity and attention and Woody was in the backseat and had no control over it and died because of it."

At 75, Steve Ritchie is one of only a few dozen fighter aces still living. Changes in technology and how wars are fought may make it unlikely that any more pilots will become aces.