Ever wondered if the coyotes in your neighborhood are a threat to you or your pets? Scientists have the same question -- and that's why a team of researchers has launched the Denver Coyote Project to study Front Range coyotes for at least the next three years.

The hope is that the results will show how aggressive or bold coyotes develop in urban areas. To do that, the Denver Coyote Project is combining observations of the animals with an analysis of their genes and hormones.

"Hopefully, we can understand how problem animals are popping up, but then also how to prevent problem animals from popping up in the first place," said Chris Schell, a post-doctoral student at Colorado State University, who will lead the project on a fellowship from the National Science Foundation.

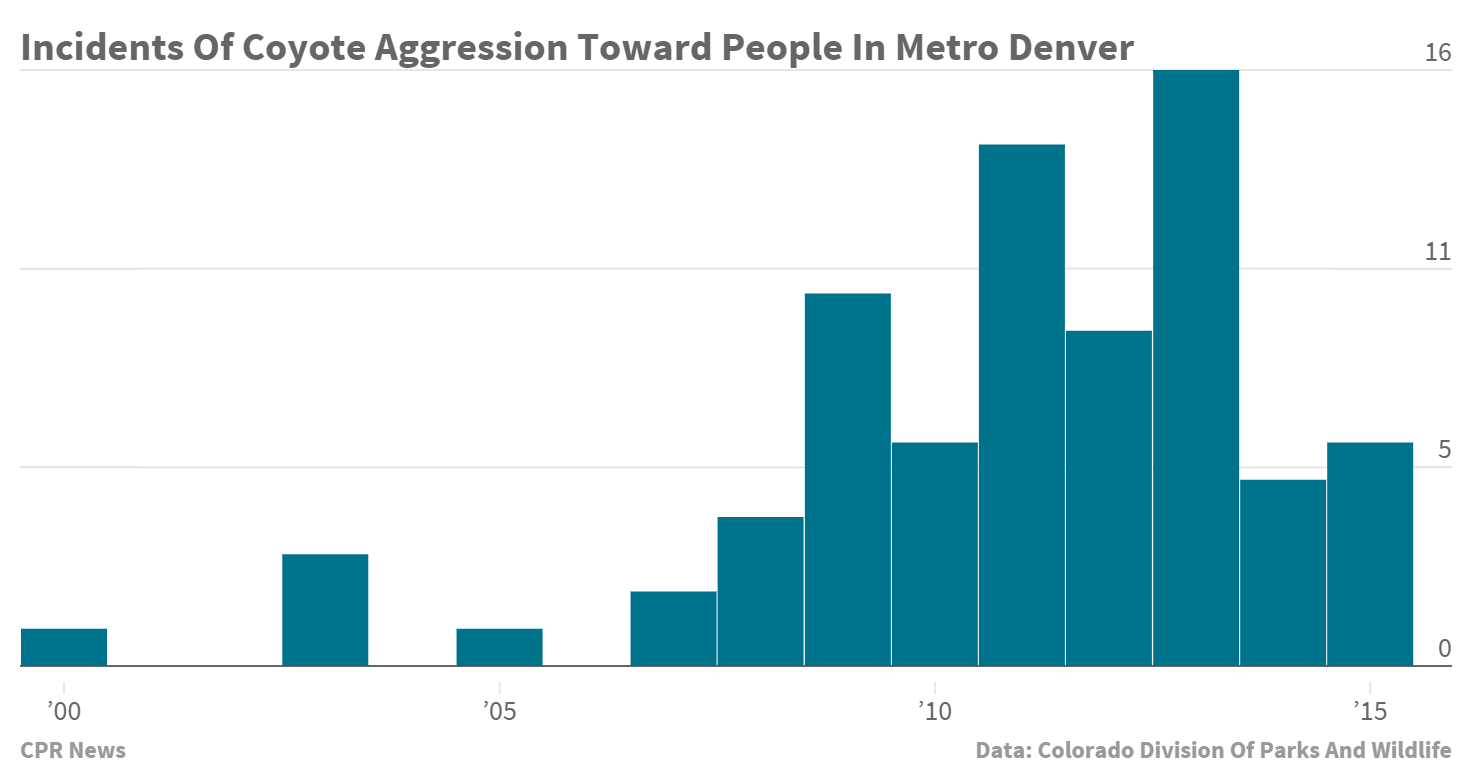

The group will look at least five different cities in the Denver-Boulder area. Their work follows up on another study conducted between 2010 and 2014, which showed that reports of problems with coyotes were rare before 2005.

Such a preventative system would be of huge help to local wildlife officials. Pete Dunlaevy, the Open Space and Trails Coordinator for the City and County of Broomfield, said his city signed on to participate in the study because it wants coyotes to be a safe part of the urban ecosystem.

"As we've had conflicts, we want to participate the research going to forward to develop better information on why those conflicts occur and what can be done to prevent them," he said.

The Problem With "Problem" Coyotes

Coyote attacks on people are rare compared to conflicts with other animals. The Colorado Division of Parks and Wildlife reports only about 25 coyote bites in the Denver area since 2007. For comparison, I-News found 6,000 reports of dog bites on the Front Range in 2012 and 2013.

Still, coyote conflicts have climbed over the last decade. Jennifer Churchill, spokeswoman for the Colorado Division of Parks and Wildlife, said she expected about one report of a coyote bite per year before 2008. Since then, the agency has recorded an average about nine per year.

But attacks on people are rarely what strains relations between the two species. The "problem" animals more often attack pets, stalk people or just hang out too close to humans. That can prompt wildlife officials to kill coyotes.

"If we believe a coyote is proving to be a human safety threat, we will do all in our power to remove that particular coyote," said Jerrie McKee, a district wildlife manager with CDPW.

Those targeted killings can stop individual coyotes from bothering people and their pets, but biologists say they do little to check the overall population. Just getting rid of coyotes is tougher than it sounds.

One study suggests that 70 percent of coyotes have to be removed in consecutive years to reduce the population. Another showed that pups born into areas with traps are more likely to survive into adulthood than those that don't face a human threat.

Moreover, getting eradicating coyotes would hurt the urban ecosystem according to Project Coyote -- a California group that pushes cities to adopt coyote coexistence plans. As the top predator in many areas, coyotes help maintain biodiversity.

All of which is to say that coyotes are incredibly adaptable and resilient. One of Chris Schell's goals for his study is to find out how those abilities have helped coyotes succeed in urban environments.

"It's a new frontier not just for these animals, but for us to figure out what factors are facilitating their success in these environments," said Schell.

Coyote Nature vs. Nurture

Scientists and wildlife officials already know that some human activities -- like feeding coyotes or letting them play with dogs -- can increase the chance of human-coyote conflicts. Schell says a focus of the study is to find out how other parts of the manmade world might influence coyote behavior.

"If we know that a lot of these problem animals develop because it's a learned behavior versus a really strong genetic component, then that really informs management," he said.

To draw that distinction learned and determined behaviors, the researchers plan to study the genetics of coyotes that wildlife officials kill. The scientists found two such animals in a freezer at the Colorado Division of Parks and Wildlife.

The data from those samples should help tell a larger story about how coyotes have colonized metro Denver. Coyotes historically have lived on the Great Plains and have only moved into cities in the last few decades. Schell suspects that the bolder coyotes may have been the first to colonize cities, which lead to behavioral differences with their rural cousins.

"Long-term, our goal is to look a rural population and urban populations and see how they differ," he said. "We could be on the foundation of understanding how urban areas themselves are ... creating different populations."

Matching Human And Coyote Cultures

Marc Bekoff, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado Boulder, worries that the study's focus on boldness and aggression could end up giving the animals a bad rap for natural behaviors.

"When I am out with people, they say a coyote is being aggressive when really it's being curious, or exploratory, or maybe assertive," he said.

For that reason, he thinks there needs to be public education on how to recognize and report on coyote behavior. And the project does try to incorporate the public with its Denver CoyoteWatch page on iNaturalist. Though only eight coyote observations have been logged on the site so far.

And whatever the outcome of the study, the scientists agree that people -- not coyotes -- will have to adapt their behavior and attitudes.

"Coyotes are here to stay, people are here to stay," said Mary Ann Bonnell, a ranger for Jefferson County Open Space and a partner on the project. "What I would love as an educator at heart is to convince people that this is the new normal."